have not the necessary data to arrive at a positive conclusion as to

the existence of a primary and peculiar cranial type among the

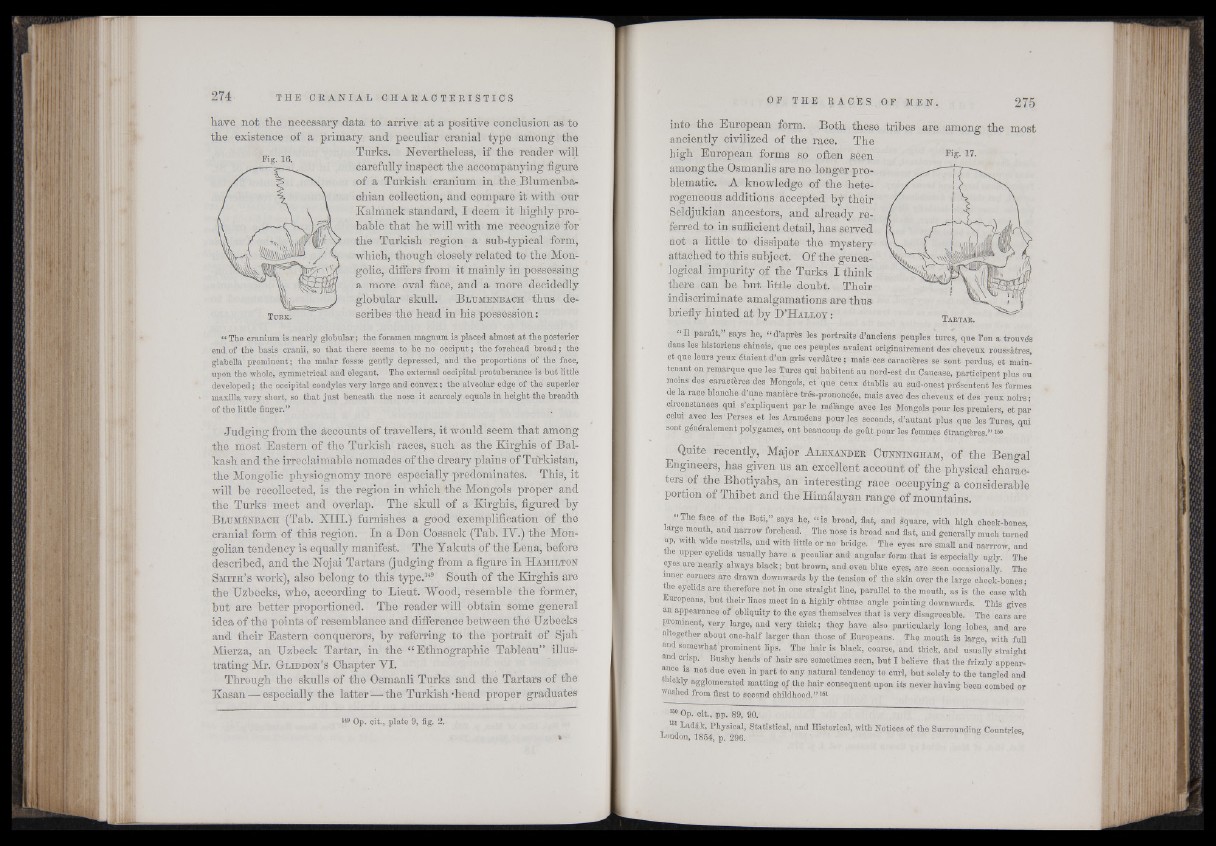

Turks. Nevertheless, if the reader will

carefully inspect the accompanying figure

of a Turkish cranium in the Blumenba-

chian collection, and compare it with our

Kalmuck standard, I deem it highly probable

that he will with me recognize for

the Turkish region a sub-typieal form,

which, though-closely related to the Mon-

golie, differs from it mainly in possessing

a more oval face, and a more decidedly

globular skull. B lu m e n b a c h thus de-

Fig. 16.

T xjp.k . scribes the head in his possession:

“ The cranium is nearly globular; the foramen magnum is placed almost,at the posterior

end of the basis cranii, so that there seems to be no occiput; the forehead broad; the

glabella prominent; the malar fossse gently depressed, and the proportions of the face,

upon the whole, symmetrical and elegant. The external occipital protuberance is but little

developed; the occipital condyles very large and convex; the alveolar edge of the superior

maxilla, very short, so that just beneath the nose it scarcely equals in height the breadth

of the little finger.”

Judging from the accounts of travellers, it would seem that among

the most Eastern of the Turkish races, such as the Kirghis-of Bal-

kash and the irreclaimable nomades of the dreary plains of Tu'rkistan,

the Mongolic physiognomy more especially predominates. This, it

will be recollected, is the region in which the Mongols proper and

the Turks meet and overlap. The skull of a Kirghis, figured by

B lumEnbach (Tab. X I IT.) furnishes a good exemplification of the

cranial form of this region. In a Don Cossack (Tab. IV.) the Mongolian

tendency is equally manifest. The Yakuts of the Lena, before

described, and the Nojai Tartars (judging from a figure in H amilton

S m ith ’s work), also belong to this type.“9. South of the Kirghis are

the TTzbecks, who, according to Lieut. Wood, resemble the former,

but are better proportioned. The reader will obtain some general

idea of the points of resemblance and difference between the Uzbecks

and their Eastern conquerors, by referring to the portrait of Sjah

Mierza, an Uzbeck Tartar, in the “ Ethnographic Tableau” illustrating

Mr. G l id d o n ’s Chapter VI.

Through the skulls of the Osmanli Turks and the Tartars of the

Kasan — especially the latter1—-the Turkish *head proper graduates

149 Op. cit., plate 9, fig. 2.

into the European form. Both these tribes are among the most

anciently civilized of the race. The

high European forms so often seen

among the Osmanlis are no longer problematic.

A knowledge of the heterogeneous

additions accepted by their

Seldjukian ancestors, and already referred

to in sufficient detail, has served

not a little to dissipate the mystery

attached to this subject. Of the genea-

' logical impurity of the Turks I think

there can be but little doubt. Their

indiscriminate amalgamations are thus

briefly hinted at by D ’H alloy :

Fig. 17.

“ R paraît,” says he, “ d’après les portraits d’anciens peuples turcs, que l’on a trouvés

dans les historiens chinois, que ces peuples avaient originairement des cheveux roussâtres,

et que leurs yeux étaient d’un gris verdâtre ; mais-ces caractères se sont perdus, et maintenant

on remarque que les Turcs qui habitent au nord-est du Caucase, participent plus ou

moins des caractères des Mongols, et'que ceux établis au sud-ouest présentent les formes

de la race blanche d’une manière trés-prononcée, mais avec des cheveux et des yeux noirs;

circonstances qui s’expliquent parle mélange avec les Mongols pour les premiers, et par

celui avec les Perses et les Araméens pour les seconds, d’autant plus que les Turcs, qui

sont généralement polygames, ont beaucoup de goût pour les femmes étrangères ” 160

Quite recently, Major A l ex a n d e r Cu n n in g h am , of the Bengal

Engineers, has given us an excellent account of the physical characters

of the Bhotiyahs, an interesting race occupying a considerable

portion of Thibet and the Himalayan range of mountains.

“ The face of the Boti,” says he, “ is broad, flat, and Square, with high cheek-bones,

Idrge mouth, and narrow forehead. The nose is broad and flat, and generally much turned

up, with wide nostrils, and with little or no bridge. The eyes are small and narrrow, and

the upper eyelids usually have a peculiar and angular form that is especially ugly. The

eyes are nearly always black ; but brown, and even blue eyes, are seen occasionally. The

inner comers are drawn downwards by the tension of the skin over the large cheek-bones;

the eyelids are therefore not in one straight line, parallel to the mouth, as is the case with

Europeans, but their lines meet in a highly obtuse angle pointing downwards. This gives

an appearance of obliquity to the eyes themselves that is very disagreeable. The ears are

prominent, very large, and very thick; they have also particularly long lobes, and are

altogether about one-half larger than those of Europeans. The mouth is large, with full

and Bomewhat'prominent lips. The hair is black, coarse, and thick, and usually straight

and crisp. Bushy heads of hair are sometimes seen, but I believe that the frizzly appearance

is not due. even in part to any natural tendency to curl, but solely to the tangled and

ickly agglomerated matting of the hair consequent upon its never having been combed or

washed from first to second childhood.” 151

150 Op. cit., pp. 89, 90.

M Ladék, Physical, Statistical, and Historical, with Notices of the Surrounding Countries

London, 1854, p. 296.