The sense of beauty was not yet sufficiently developed among

Greek artists ; but it is remarkable that even in its rudiments Greek

art, unlike the Egyptian,17? had nothing to do with portraits; it was

not the king, but the hero and the god who became the objects of

the artist’s creation, blot less striking is the complete absence of

the landscape in Grecian art. The human form and: animated nature

are for the Greek the exclusive object of representation; accordingly,

he personifies day and night, the sun and the moon, time and the

seasons, the earth-and the sea, the mountains and the rivers; he gives

them the features of men; but the human figure he draws is always

a type of the race, not the effigy of an individual.

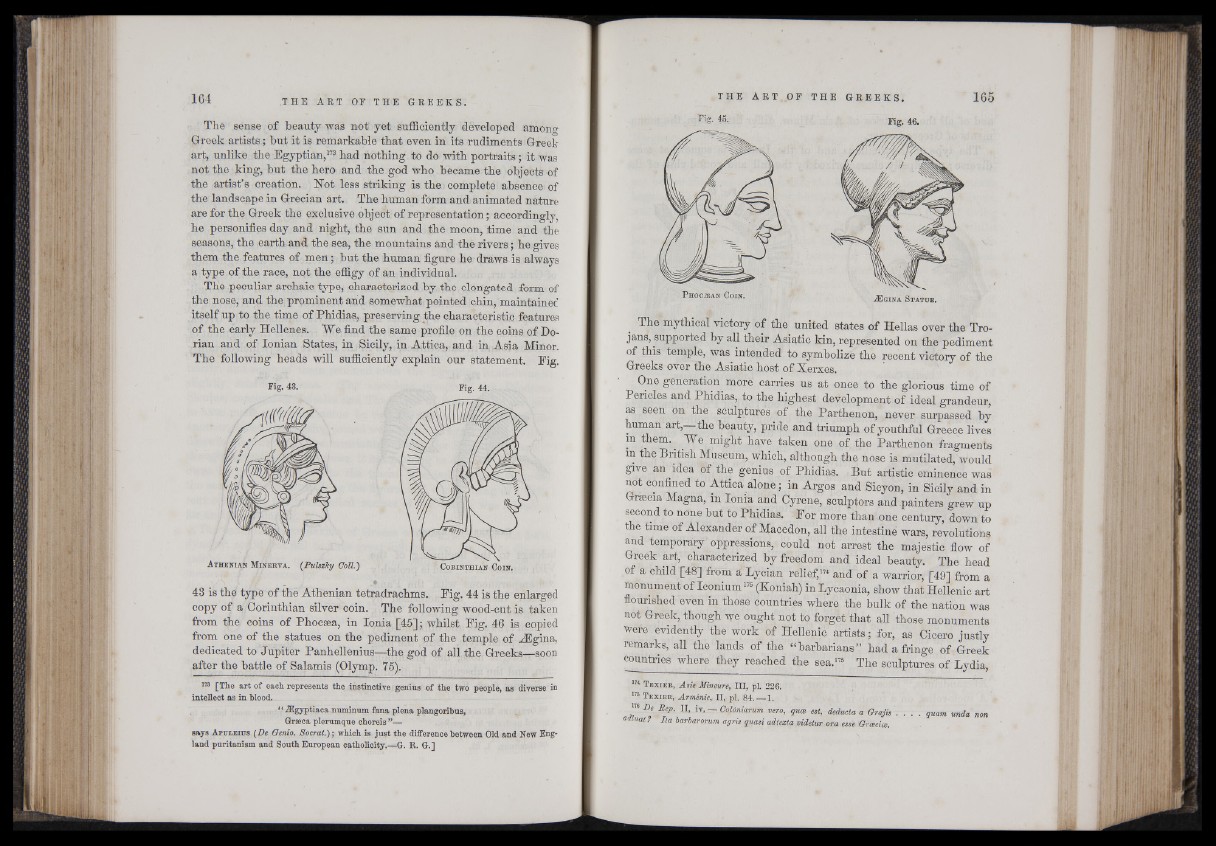

The peculiar archaic type, characterized by the elongated form of

the nose, and the prominent and somewhat pointed chin, maintained

itself up to the time of Phidias, preserving the characteristic features

of the early Hellenes. We find the same profile on the coins of Dorian

and of Ionian States, in Sicily, in Attica, and in Asia Minor.

The following heads will sufficiently explain our statement. Fig.

Fig. 43. Fig. 44.

A t h e n ia n M in e r v a . (Pulszky Coll.)

43 is the type of the Athenian tetradrachms. Fig. 44 is the enlarged

copy of a Corinthian silver coin. The following wood-cut is taken

from the coins of Phocsea, in Ionia [45]; whilst Fig. 46 is copied

from one of the statues on the pediment pf the temple of kEgina,

dedicated to Jupiter Panhellenius—the god of all the Greeks—-soon

after the battle of Salamis (Olymp. 75).

173 [The art of each represents the instinctive genius of the two people, as diverse in

intellect as in blood.

“ -ffigyptiaca numinum fana plena plangoribus,

Grseca plerumque choreis ”—

says Apuleitts [De Genio. Socral. ) ; which is just the difference between Old and New England

puritanism and South European catholicity.—G. R. G.]

Fis- 45' Fig. 46.

_ The mythical victory of the united states of Hellas over the Trojans,

supported by all their Asiatic kin, represented on the pediment

of this temple, was intended to symbolize the recent victory of the

Greeks over the Asiatic host of Xerxes.

One generation more carries us at once to the glorious time of

Pericles and Phidias, to the highest development of ideal grandeur,

as seen on the sculptures of the Parthenon, never surpassed by

human art,—the beauty, pride and triumph of youthful Greece lives

m them. We might have taken one of the Parthenon fragments

m the British Museum, which, although the nose is mutilated, would

give an idea of the genius of Phidias. But artistic eminence was

not confined to Attica alone; in Argos and Sicyon, in Sicily and in

Grsecia Magna, m Ionia and Cyrene, sculptors and painters grew up

second to none but to Phidias. For more than one century, down to

the time of Alexander of Macedon, all the intestine wars, revolutions

and temporary oppressions, could not arrest the majestic flow of

Greek art, characterized by freedom and ideal beauty. The head

of a child [48] from a Lycian relief,174 and of a warrior, [49] from a

monument of Iconium175 (Koniah) in Lycaonia, show that Hellenic art

flourished even in those countries where the bulk of the nation was

not Greek, though we ought not to forget that all those monuments

were evidently the work of Hellenic artists; for, as Cicero justly

remarks, all the lands of the “barbarians” had a fringe of Greek

countries where they reached the sea.175 The sculptures of Lydia,

1M Texier, Asie Mineure, III, pi. 226.

175 Texier, Armenief II, pi. 84. — 1.

H H P f l 1V> - omniarum vero, qua est, deducta a Graji* . . . . quam unda non

* Ita barbarorum agris gxiasi adtexta videtur ora esse Grcecice.