rigid archaic style of the Tuscan hronze-figures;160 the later Doric

style, carried to Tarquinii from Corinth by Demaratus, which char

racterizes the potteries of Italy; and perhaps a still later Attic style,

chaste and dignified, such as we admire on the best Etruscan vases.

Inasmuch, however, as all the names of the artists inscribed on the

vases, the alphabet of the inscriptions, and the style of the drawing,

are exclusively Grecian, there are many archaeologists who do not

attribute them to Etruria, but believe they may have either been

imported from Greece, or manufactured in Etruria by guilds of Greek

artists who maintained their nationality in the midst of the Tuscans.

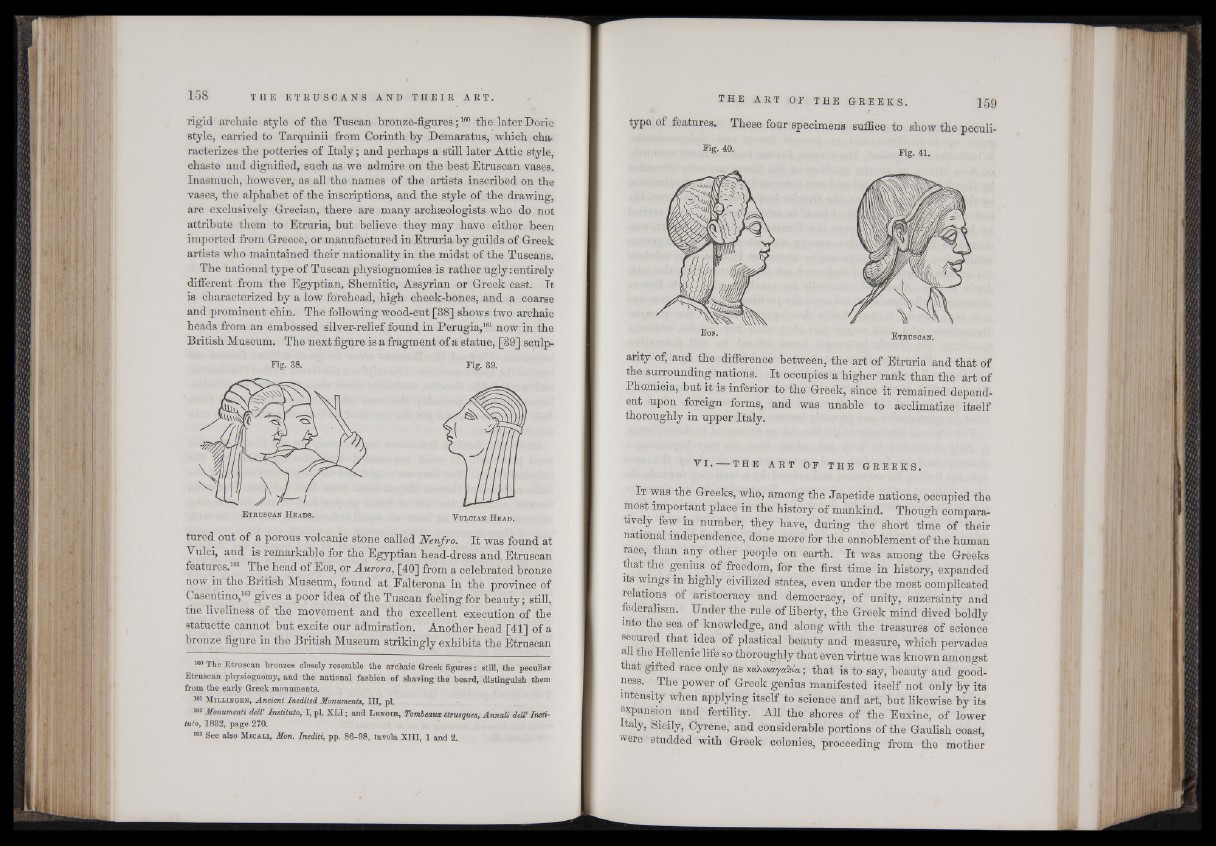

The national type of Tuscan physiognomies is rather ugly:entirely

different from the Egyptian, Shemitic, Assyrian or Greek cast. It

is characterized by a low forehead, high cheek-bones, and a coarse

and prominent chin. The following wood-cut [38] shows two archaic

heads from an embossed silver-relief found in Perugia,161 now in the

British Museum. The next figure is a fragment of a statue, [39] sculp-

Fig. 38. Fig. 39.

tured out of a porous volcanic stone called Nenfro. It was found at

Vulci, and is remarkable for the Egyptian head-dress and Etruscan

features.162 The head of Eos, or Aurora, [40] from a celebrated bronze

now in the British Museum, found at Falterona in the province of

Casentino,163 gives a poor idea of the Tuscan feeling for beauty; still,

the liveliness of the movement and the excellent execution of the

statuette cannot but excite our admiration. Another head [41] of a

bronze figure in the British Museum strikingly exhibits the Etruscan

160 The Etruscan bronzes closely resemble the archaic Greek figures: still, the peculiar

Etruscan physiognomy, and the national fashion of shaving the beard, distinguish them

from the early Greek monuments.

161 Millingen, Ancient Inedited Monuments, HE, pi.

162 Monumenti delV Instituto, I, pi. XLI; and L e n o ir , Tombeauz ¿trueques, Annali deffl Instituto,

1832, page 270.

163 See also Micali, Mon. Inediti, pp. 86-98, tavola XIII, 1 and 2.

type of features. These four specimens suffice to show the peculios

40- Fig. 41.

Eos- Etbcsoan.

anty of, and the difference between, the art of Etruria and that of

the surrounding nations. It occupies a higher rank than the art of

Phoenicia, but it is inferior to the Greek, since it remained dependent

upon foreign forms, and was unable to acclimatize itself

thoroughly in upper Italy.

V I . — T H E A R T OF T H E G R E E K S .

I t was the Greeks, who, among the Japetide nations, occupied the

most important place in the history of mankind. Though comparatively

few in number, they have, during the short time of their

national independence, done more for the ennoblement of the human

race, than any other people on earth. It was among the Greeks

that the genius of freedom, for the first time in history, expanded

its wings in highly civilized states, even under the most complicated

relations of aristocracy and democracy, of unily, suzerainty and

federalism. Under the rule of liberty, the Greek mind dived boldly

mto the sea of knowledge, and along with the treasures of science

secured that idea of plastical beauty and measure, which pervades

all the Hellenic life so thoroughly that even virtue was known amongst

that gifted race only as xukoxaya&G; that is to say, beauty and goodness.

^ The power of Greek genius manifested itself not only by its

intensity when applying itself to science and art, but likewise by its

expansion and fertility. All the shores of the Euxine, of lower

Italy, Sicily, Cyrene, and considerable portions of the Gaulish coast,

were studded with Greek colonies, proceeding from the mother