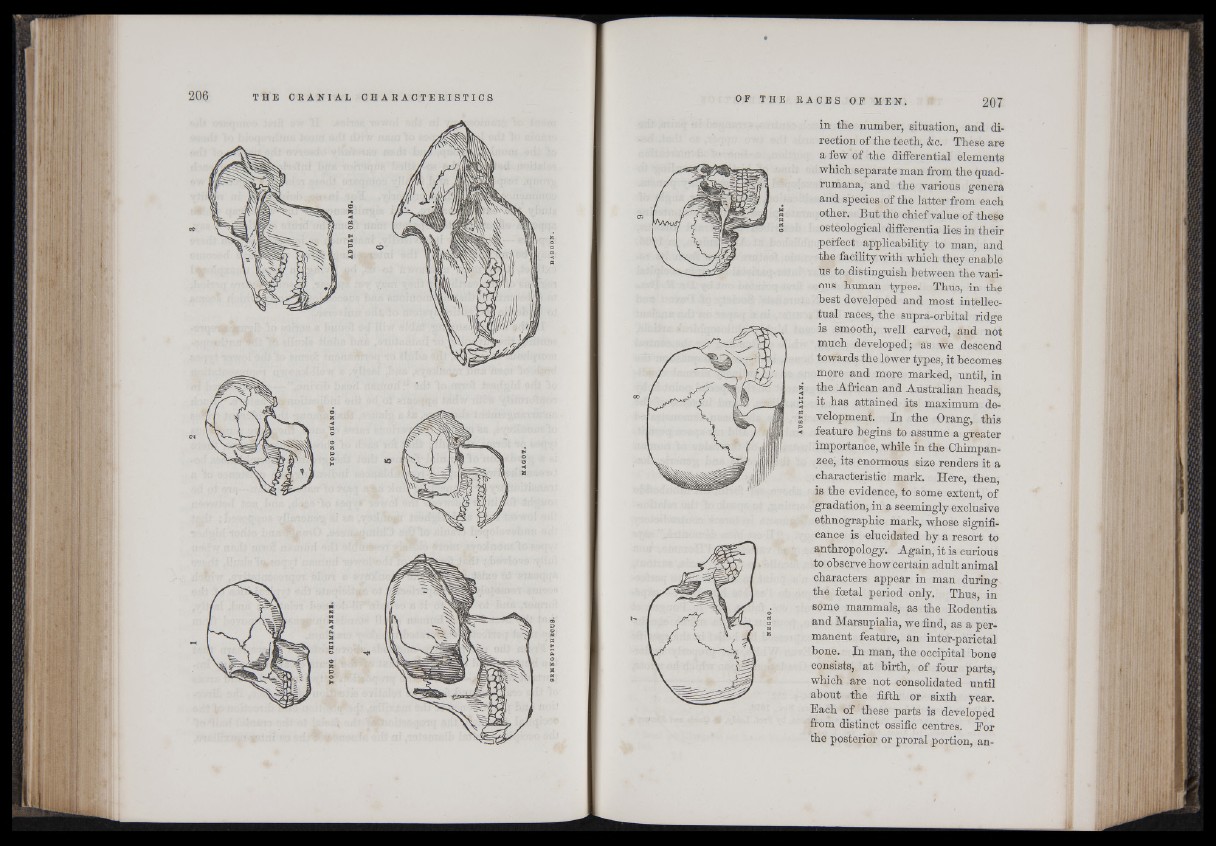

in the number, situation, and direction

of the teeth, &c. These are

a few of the differential elements

which separate man from the quad-

rumana, and the various genera

and species of the latter from each

other. But the chief value of these

osteological differentia lies in their

perfect applicability to man, and

the facility with which they enable

us to distinguish between the various

human types. Thus, in the

best developed and most intellectual

races, the supra-orbital ridge

is smooth, well carved, and not

much developed; as we descend

towards the lower types, it becomes

more and more marked, until, in

* the African and Australian heads,

5 it has attained its maximum deÎ

velopment. In the Orang, this

5 feature begins to assume a greater

importance, while in the Chimpanzee;

its enormous size renders it a

characteristic mark. Here, then,

is the evidence, to some extent, of

gradation, in a seemingly exclusive

ethnographic mark, whose significance

is elucidated by a resort to

anthropology. Again, it is curious

to observe how certain adult animal

characters appear in man during

the foetal period only. Thus, in

some mammals, as the Bodentia

and Marsupialia, we find, as a permanent

feature, an inter-parietal

hone. In man, the occipital hone

consists, at birth, of four parts,

which are not consolidated until

about the fifth or sixth year.

Each of these parts is developed

from distinct ossific centres. Eor

the posterior or proral portion, an