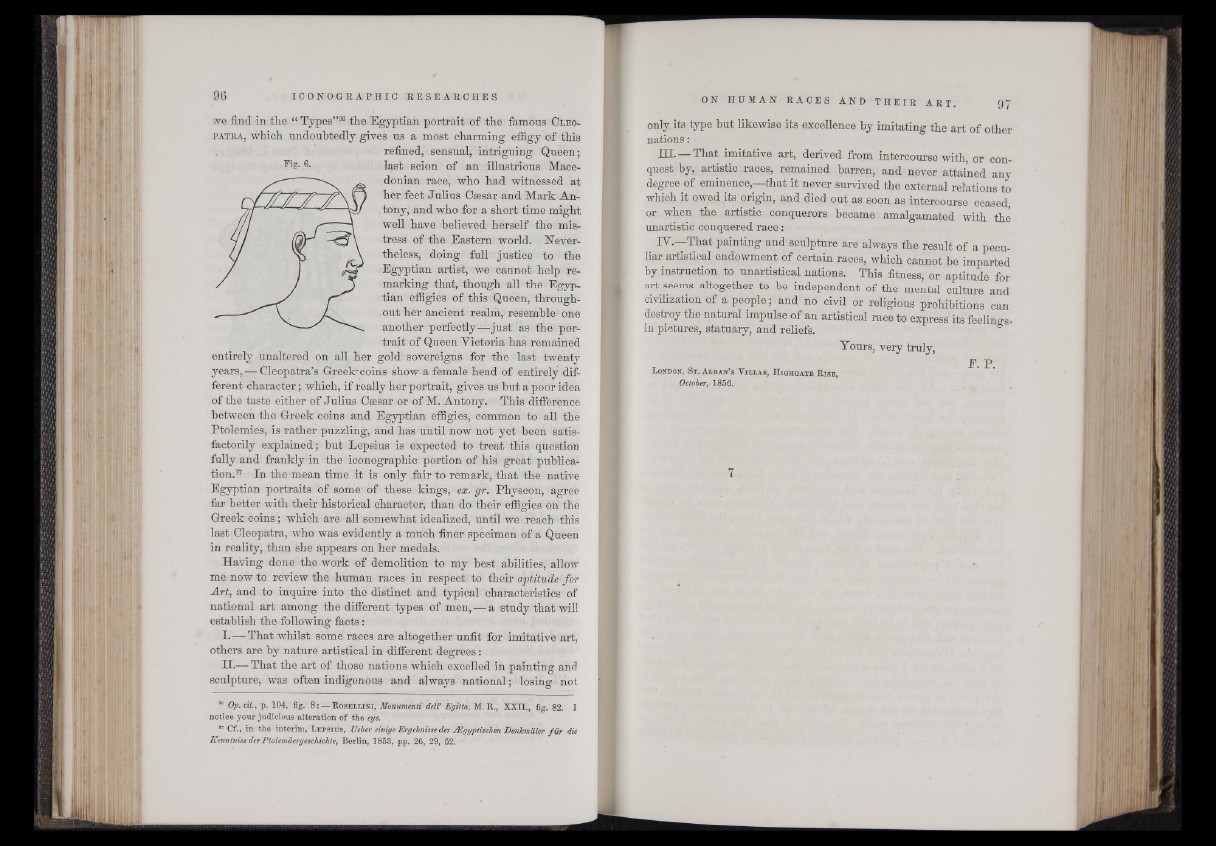

we find in the “ Types”36 the Egyptian portrait of the famous C l e o p

a t r a , which undoubtedly gives us a most charming effigy of this

refined, sensual, intriguing Queen;

Fls- 6- last scion of an illustrious Macedonian

race, who had witnessed at

her feet Julius Csesar and Mark Antony,

and who for a short time might

well have believed herself the mistress

of the Eastern world. Nevertheless,

doing full justice to the

Egyptian artist, we cannot help remarking

that, though all the Egyptian

efligies of this Queen, throughout

her ancient realm, resemble one

another perfectly-—-just as the portrait

of Queen Victoria has remained

entirely unaltered on all her gold sovereigns for the last twenty

years,— Cleopatra’s Greek' coins show a female head of entirely different

character; which, if really her portrait, gives us hut a poor idea

of the taste either of Julius Csesar or of M. Antony. This difference

between the Greek coins and Egyptian effigies, common to all the

Ptolemies, is rather puzzling, and has until now not yet been satisfactorily

explained; but Lepsius is expected to treat this question

fully and frankly in the iconographic portion of his great publication.

37 In the mean time it is only fair to remark, that the native

Egyptian portraits of some' of these kings, ex. gr. Physcon, agree

far better with their historical character, than do their effigies on the

Greek coins; which are all somewhat idealized, until we reach this

last Cleopatra, who was evidently a much finer Specimen of a Queen

in reality, than she appears on her medals.

Having done the work of demolition to my best abilities, allow

me now to review the human races in respect to their aptitude for

Art, and to inquire into the distinct and typical characteristics of

national art among the different types of men, — a study that will

establish the following facts:

I. — That whilst some races are altogether unfit for imitative art,

others are by nature artistical in different degrees:

H.— That the art of those nations which excelled in painting and

sculpture, was often indigenous and always national; losing not

“ Op.cit., p. 104, fig. 8: — R o s e l l in i , Monumenti delC Egitto, M.R., XXII., fig. 82. I

notice your judicious alteration of the eye.

87 Cf., m the interim, L e p s iu s , Ueber einige Ergebnisse der ägyptischen Denkmäler fü r die

Kenntniss derPlolemäergeschichte, Berlin, 1853, pp. 26, 29, 52. '

only its type but likewise its excellence by imitating the art of other

nations:

HI. — That imitative art, derived frora intercourse with, or conquest

by, artistic races, remained barren, and never attained any

degree of eminence,—that it never survived the external relations to

which it owed its origin, and died out as soon as intercourse ceased,

or when the artistic conquerors became amalgamated with the

unartistie conquered race:

IV.—That painting and sculpture are always the result of a peculiar

artistical endowment of certain races, which cannot he imparted

by instruction to unartistical nations. This fitness, or aptitude for

art^ seems altogether to be independent of the mental culture and

civilization of a people; and no civil or religious prohibitions can

destroy the natural impulse of an artistical race to express its feelings,

in pictures, statuaiy, and reliefs.

Tours, very truly,

E. P.

L ondon, S t . A l b a n ’s V il l a s , H io h g a t e R i s e ,

October, 1856.

7