copy nature with fidelity. It corresponds in style to the superb torso

o f P sam e tik H. found at Sais,

and long in the public library

at Cambridge.81

This second revival of Egypt

was not confined to sculpture.

"We see once more, as in the

time of R ames se s and O sorchon,

(XVIIIth and XXIId dynasties,

t. e. in the 15th and 10th centuries

b . c.) a most striking

parallel between the intellectual

and artistic life of the nation.

The new naturalistic phase of

Egyptian art coincides with an

analogous, most important step

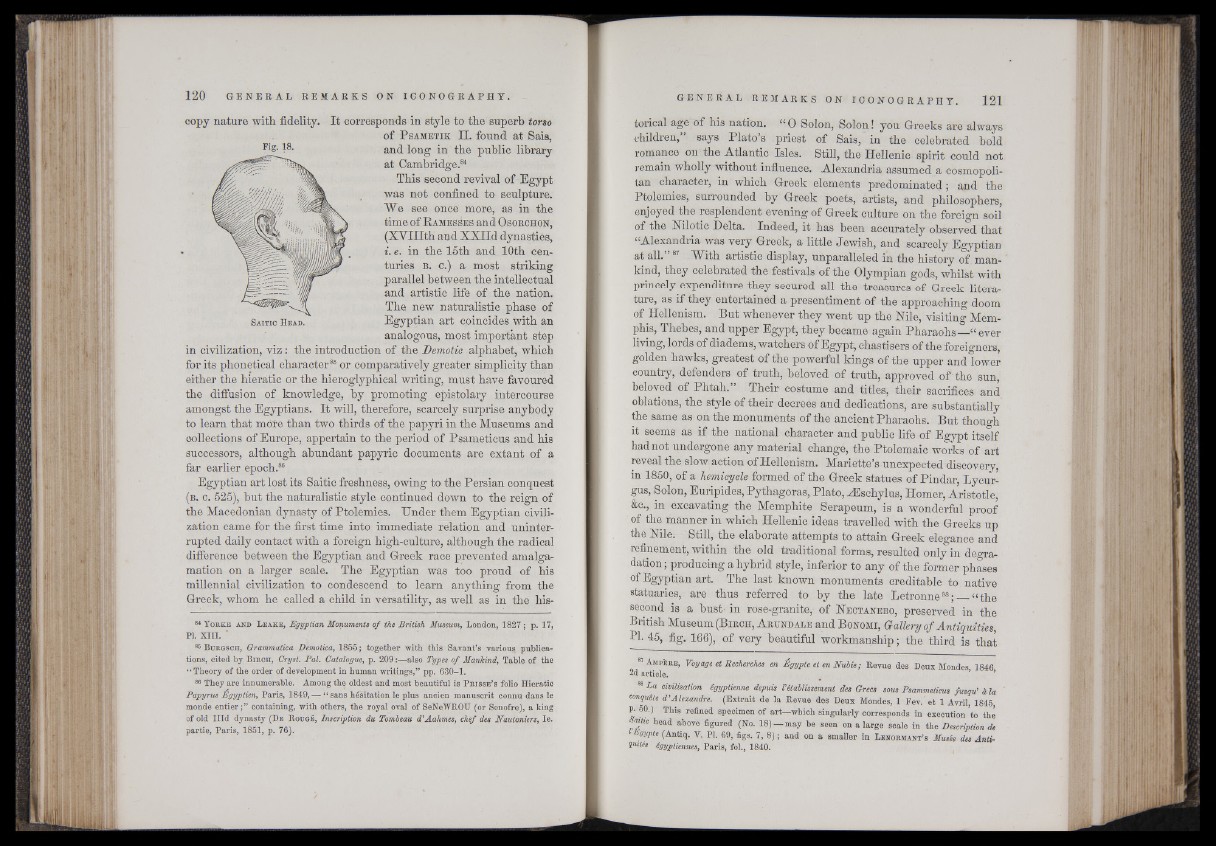

Fig. 18.

S a it ic H e a d .

in civilization, viz : the introduction of the Demotic alphabet, which

for its phonetical character85 or comparatively greater simplicity than

either the hieratic or the hieroglyphical writing, must have favoured

the diffusion of knowledge, by promoting epistolary intercourse

amongst the Egyptians. It will, therefore, scarcely surprise anybody

to learn that more than two thirds of the papyri in the Museums and

collections of Europe, appertain to the period of Psameticus and his

successors, although abundant papyric documents are extant of a

far earlier epoch.86

Egyptian art lost its Saitic freshness, owing to the Persian conquest

(b , c. 525), but the naturalistic style continued down to the reign of

the Macedonian dynasty of Ptolemies. Under them Egyptian civilization

came for the first time into immediate relation and uninterrupted

daily contact with a foreign high-culture, although the radical

difference between the Egyptian and Greek race prevented amalgamation

on a larger scale. The Egyptian was too proud of his

millennial civilization to condescend to learn anything from the

Greek, whom he called a child in versatility, as well as in the his84

Y o r k e a n d L e a k e , Egyptian Monuments of the British Museum, London, 1827 ; p. 17,

PI. XIII. *

85 B u r g s c h , Grammatica Demotica, 1855 ; together with this Savant’s varions publications,

cited by B ir c h , Cryst. Pal. Catalogue, p. 209 .-—also Types of Mankind, Table of the

“ Theory of the order of development in human writings,” pp. 630—1.

86 They are innumerable. Among the oldest and most beautiful is P r is s e ’s folio Hieratic

Papyrus Égyptien, Paris, 1849, — “ sans hésitation le plus ancien manuscrit connu dans le

monde entier containing, with others, the royal oval of SeNeWROU (or Senofre), a king

of old Illd dynasty (D e R o ug e , Inscription du Tombeau d ’Aahmes, chef des NautonierSj Ie.

partie, Paris, 1851, p. 76).

torical age of his nation. “ 0 Solon, Solon! you Greeks are always

children,” says Plato’s priest of Sais, in the celebrated bold

romance on the Atlantic Isles. Still, the Hellenic spirit could not

remain wholly without influence. Alexandria assumed a cosmopolitan

character, in which Greek elements predominated ; and the

Ptolemies, surrounded by Greek poets, artists, and philosophers,

enjoyed the resplendent evening of Greek culture on the foreign soil

of the Nilotic Delta. Indeed, it has been accurately observed that

“Alexandiia was very Greek, a little Jewish, and scarcely Egyptian

at all.” 87 With artistic display, unparalleled in the histoiy of mankind,

they celebrated the festivals of the Olympian gods, whilst with

princely expenditure they secured all the treasures of Greek literature,

as if they entertained a presentiment of the approaching doom

of Hellenism. But whenever they went up the Nile, visiting Memphis,

Thebes, and upper Egypt, they became again Pharaohs—“ ever

living, lords of diadems, watchers of Egypt, chastisers of the foreigners,

golden hawks, greatest of the powerful kings of the upper and lower

country, defenders of truth, beloved of truth, approved of the sun,

beloved of Phtah.” Their costume and titles, their sacrifices and

oblations, the style of their decrees and dedications, are substantially

the same as on the monuments of the ancient Pharaohs. But though

it seems as if the national character and public life of Egypt itself

had not undergone any material change, the Ptolemaic works of art

reveal the slow action of Hellenism. Mariette’s unexpected discovery,

in 1850, of a hemicycle formed of the Greek statues of Pindar, Lycur-

gus, Solon, Euripides, Pythagoras, Plato, JEschylus, Homer, Aristotle,

&c., in excavating the Memphite Serapeum, is a wonderful proof

of the manner in which Hellenic ideas travelled with the Greeks up

the Nile. Still, the elaborate attempts to attain Greek elegance and

refinement, within the old traditional forms, resulted only in degradation

; producing a hybrid style, inferior to any of the former phases

of Egyptian art. The last known monuments creditable to native

statuaries, are thus referred to by the late Letronne88; “ the

second is a bust- in rose-granite, of N ectanebo, preserved in the

British Museum (B ir c h , A r u n d ale and B onomi, Gallery of Antiquities

PI- 45, fig. 166), of very beautiful workmanship ; the third is that

81 A m p è r e , Voyage el Recherches en Égyple el en Nubie ; Revue des Deux Mondes 1846

2d article.

88 La civilisation égyptienne depuis l'établissement des Grecs sous Psammeticus jusqu’ à la '

conquête d ’Alexandre. (Extrait de la Revue des Deux Mondes, 1 Fev.'et 1 Avril, 1845,

P- 60.) This refined specimen of art—which singularly corresponds in execution ’to the

head above figured (No. 18) — may be seen on a large scale in the Description de

9yple (Antiq. V. PI. 69, figs. 7, 8) ; and on a smaller in Lenormant’s Musée des Antiquités

égyptiennes, Paris, fol., 1840.