still lives and moves in the “ Trasteverini,” or mob population of the

Tiber.

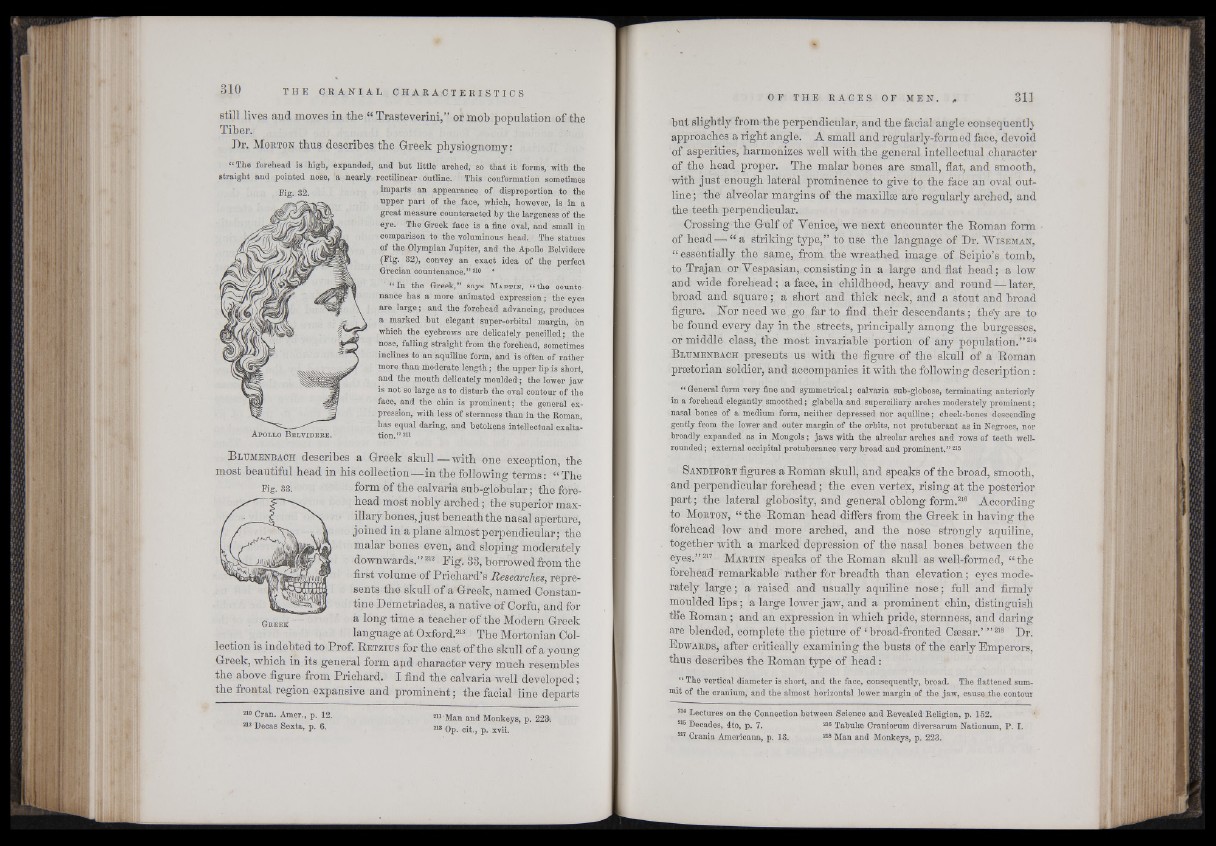

Dr. M orton thus describes the Greek physiognomy:

“ The forehead is high, expanded, and but little arched, so that it forms, with the

straight and pointed nose, a nearly rectilinear Outline. 1 This conformation sometimes

Eig. 32. imparts an appearance of disproportion to the

upper part of the face, which, however, is in a

great measure counteracted by the largeness of the

eye. The Greek face is a fine oval, and small in

comparison to the voluminous head. The statues

of the Olympian Jupiter, and the Apollo Belvidere

(Fig. 82), convey an exact idea of the perfect

Grecian countenance.51210 *

“ In the Greek,” says M a r t in , “ the countenance

has a more animated expression; the eyes

are large; and the forehead advancing, produces

a marked but elegant super-orbital margin, bn

which the eyebrows are delicately pencilled; the

nose, falling straight from the forehead, sometimes

inclines to an aquiline form, and is often of rather

more than moderate length; the upper lip is short,

and the mouth delicately moulded; the lower jaw

is not so large as to disturb the oval contour of the

face, and the chin is prominent; the general expression,

with less of sternness than in the Roman,

has equal daring, and betokens intellectual exalta-

A po l l o B e l v id b r e . tion.” 211

B ltjmenbach describes a Greek skull — with, one - exception, the

most beautiful head in his collection—in the following terms: “ The

Fig. 33. form of the calvaría sub-globular; the forehead

most nobly arched; the superior maxillary

bones, just beneath the nasal aperture,

joined in aplane almost perpendicular; the

malar bones even, and sloping moderately

downwards.”213 Big. 33, borrowed from the

first volume of Prichard’s Researches, represents

the skull of a Greek, named Constantine

Demetriades, a native of Corfu, and for

Geí¡ek: a long time a teacher of the Modern Greek

language at Oxford.213 The Mortonian Collection

is indebted to Prof. R e tz iu s for the east of the skull of a young

Greek, which in its general form apd character very much resembles

the above figure from Prichard. I find the calvaría well developed;

the frontal region expansive and prominent; the facial line departs

Cran. Amer., p. 12.

az Becas Sexta, p. 6.

211 'Man and Monkeys, p. 223>.

213 Op. oit., p. xvii.

but slightly from the perpendicular, and the facial angle consequent]}

approaches a right angle. A small and regularly-formed face, devoid

of asperities, harmonizes well with the general intellectual character

of the head proper. The malar bones are small, flat, and smooth,

with just enough lateral prominence to give to the face an oval outline;

the alveolar margins of the maxillae are regularly arched, and

the teeth perpendicular.

Crossing the Gulf of Venice, we next encounter the Roman form

of head — | a striking type,” to use the language of Dr. W isem a n ,

“ essentially the same, from the wreathed image of Scipio’s tomb,

to Trajan or Vespasian, consisting in a large and flat head; a low

and wide forehead ; a face, in childhood, heavy and round — later,

broad and square; a short and thick neck, and a stout and broad

figure. hTor need we go far to find their descendants; they are to

be found every day in the streets, principally among the burgesses,

or middle class, the most invariable portion of any population.”214

B ltjmenbach presents, us with the figure of the skull of a Roman

praetorian soldier, and accompanies it with the following description:

11 General form very fine and symmetrical; calvaria sub-globose, terminating anteriorly

in a forehead elegantly smoothed; glabella and superciliary arches moderately prominent;

nasal bones of a medium form, neither depressed nor aquiline; cheek-bones descending

gently from the lower and outer margin of the orbits, hot protuberant as in Negroes, nor

broadly expanded as in Mongols; jaws with the alveolar arches and rows of teeth well-

rounded; external occipital protuberance very broad and prominent.” 215

S a n d ifo r t figures a Roman skull, and speaks of the broad, smooth,

and perpendicular forehead; the even vertex, rising at the posterior

part; the lateral globosity, and general oblong form.216 According

to M orton, “ the Roman head differs from the Greek in having the

forehead low and more arched, and the nose strongly aquiline,

together with a marked depression of the nasal bones between the

eyes.”217 M a r t in speaks of the Roman skull as well-formed, “ the

forehead remarkable rather for breadth than elevation; eyes moderately

large; a raised and usually aquiline nose; full and firmly

moulded lips; a large lower jaw, and a prominent chin, distinguish

the Roman; and an expression in which pride, sternness, and daring

are blended, complete the picture of ‘broad-fronted Csesar.’ ”218 Dr.

E dwards, after critically examining the busts of the early Emperors,

thus describes the Roman type of head:

“ The vertical diameter is short, and the face, consequently, broad. The flattened sum,

nut of the cranium, and the almost horizontal lower margin of the jaw, cause the contour

2W Lectures on the Connection between Science and Revealed Religion, p. 152.

215 Decades, 4to, p. 7. 216 Tabulae Craniorum diversarum Nationum, P. I.

217 Crania Americana, p. 13. 218 Man and Monkeys, p. 223.