/er was stopped by “ barbarians,” but only by the equally powerful

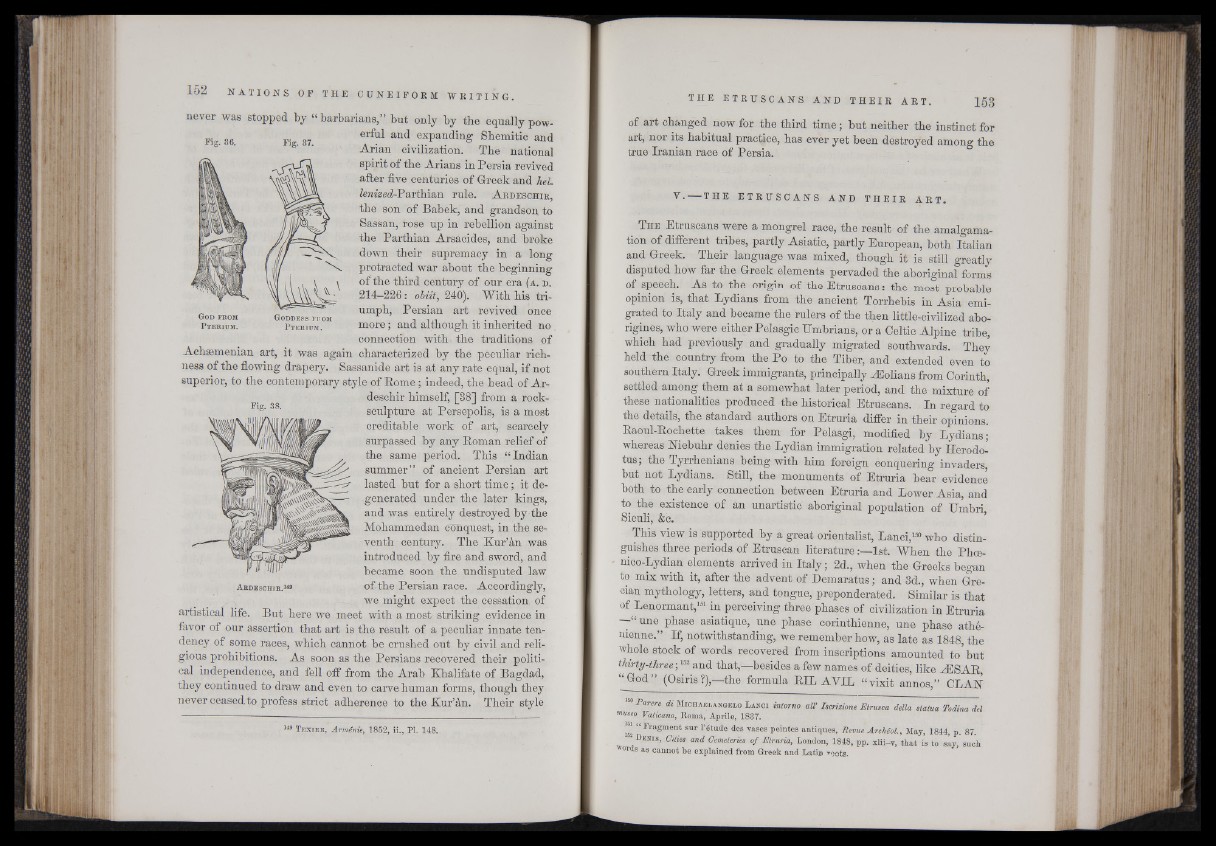

Fig. 36. Fig. 87.

Goddess fpom

P terium.

and expanding Shemitic and

Arian civilization. The national

spirit of the Arians in Persia revived

after five centuries of G-reek and heL

Tem'zed-Parthian rule. A r d e sc h ir ,

the son of Babek, and grandson to

Sassan, rose up in rebellion against

the Parthian Arsacides, and broke

down their supremacy in a long

protracted war about the beginning

of the third century of our era (a . d .

214-226 : obiit, 240). With his triumph,

Persian art revived once

more ; and although it inherited no

connection with the traditions of

Achæmenian art, it was again characterized by the peculiar richness

of the flowing drapery. Sassanide art is at any rate equal, if not

superior, to the contemporary style of Rome ; indeed, the head of A rdeschir

himself, [38] from a rock-

sculpture at Persepolis, is a most

creditable work of art, scarcely

surpassed by any Roman relief of

the same period. This “ Indian

summer” of ancient Persian art

lasted but for a short time ; it degenerated

under the later kings,

and was entirely destroyed by the

Mohammedan conquest, in the seventh

century. The Kur’àn was

introduced by fire and sword, and

became soon the undisputed law

of the Persian race. Accordingly,

we might expect the cessation of

Fig. 38.

A r d e s c h i r . 149

artistical life. But here we meet with a most striking evidence in

favor of our assertion that art is the result of a peculiar innate tendency

of some races, which cannot be crushed out by civil , and religious

prohibitions. As soon as the Persians recovered their political

independence, and fell off from the Arab Ehalifate of Bagdad,

they continued to draw and even to carve human forms, though they

never ceased to profess strict adherence to the Kur’àn. Their style

149 Texter, Arménie, 1852, ii., PL 148.

of art changed now for the third time; but neither the instinct for

art, nor its habitual practice, has ever yet been destroyed among the

true Iranian race of Persia.

T . — THE E T R U S C A N S A N D T H E I R A R T .

T he Etruscans were a mongrel race, the result of the amalgama-

tion of different tribes, partly Asiatic, partly European, both Italian

and Greek. Their language was mixed, though it is still greatly

disputed how far the Greek elements pervaded the aboriginal forms

of speech. As to the origin of the Etruscans : the most probable

opinion is, that Lydians from the ancient Torrhebis in Asia emigrated

to Italy and became the rulers of the then little-civilized aborigines,

who were either Pelasgic Umbrians, or a Celtic Alpine tribe,

which had previously and gradually migrated southwards. They

held the country from the Po to the Tiber, and extended even to

southern Italy. Greek immigrants, principally ASolians from Corinth,

settled among them at a somewhat later period, and the mixture of

these nationalities produced the historical Etruscans. In regard to

the details, the standard authors on Etruria differ in their opinions.

Raoul-Rochette takes them for Pelasgi, modified by Lydians,"

whereas Kiebuhr denies the Lydian immigration related by Herodo-

tus ; the Tyrrhenians being with him foreign conquering invaders,

but not Lydians. Still, the monuments of Etruria bear evidence

both to the early connection between Etruria and Lower Asia, and

to the existence of an unartistic aboriginal population of Umbri

Siculi, &c.

This view is supported by a great orientalist, Lanci,150 who distinguishes

three periods of Etruscan literature 1st. When the Phce-

nico-Lydian elements arrived in Italy; 2d., when the Greeks began

to mix with it, after the advent of Demaratus; and 3d., when Grecian

mythology, letters, and tongue, preponderated. Similar is that

of Lenormant,151 in perceiving three phases of civilization in Etruria

—-“ une phase asiatique, une phase corinthienne, une phase athénienne.”

If, notwithstanding, we remember how, as late as 1848, the

whole stock of words recovered from inscriptions amounted to’but

thirty-three ;152 and that,—besides a few names of deities, like ASSAR,

“God” (Osiris?),—the formula RLL AYLL “ vixit annos,” CLAST

50 Parera di Miohajsj.anhei,o Lanoi intorno all’ lacrizione Etruaca della alalua Todina del

nuseo Yalicano, Roma, Aprile, 1837.

1S2 ' Fragment sur des vases peintes antiques, Revue Archéol, May, 1844, p. 87.

2 Dismis, Gitiea and Oemeleriea of Etruria, London, 1848, pp. xlii-v, that is to sly, such

ords as cannot be explained from Greek and Latin roots.