forms, but also to exbibit a few of those inferior types through which

the human family, in obedience to a grand and deeply underlying

law of organic unity, seeks to connect itself with the great animal

series of which it is the undoubted head and front.

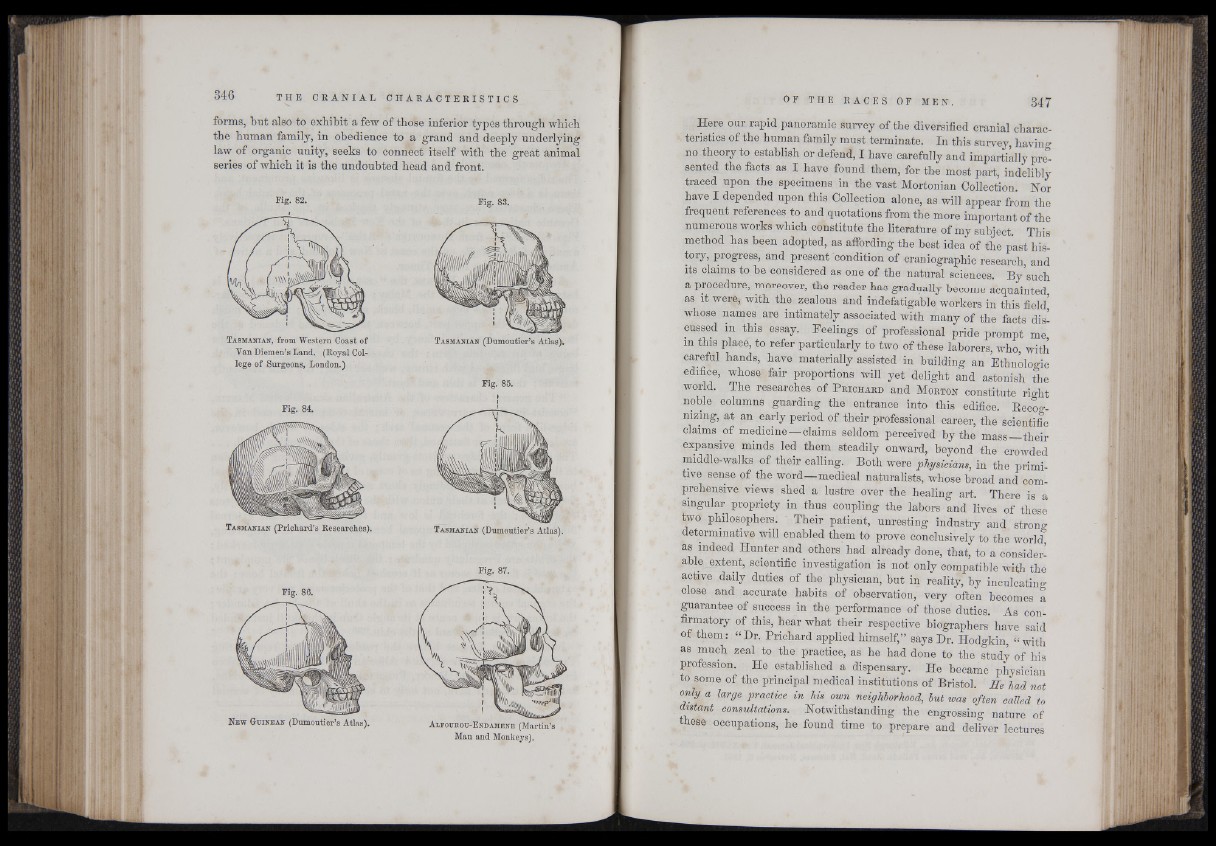

Fig. 82.

T a s m a n i a » (Prichard’s Researches).

Fig. 83.

T a s m a n i a n , from Western Coast of

Van Diemen’s Land. (Royal College

of Surgeons, London.)

Fig. 84.

T a s m a n i a n (Dumoutier’s Atlas).

Fig. 85.

i

T a s m a n i a n (Dumoutier’s Atlas).

Fig. 88.

Fig. 87.

N e w G u i n e a n (Dumoutier’s Atlas). A l f o u b o u - E n h a m e n f , (Martin’s

Man and Monkeys).

Here our rapid panoramic survey of the diversified cranial characteristics

of the human family must terminate. In this survey, having

no theory to establish or defend, I have carefully and impartially presented

the facts as I have found them, for the most part, indelibly

traced upon the specimens in the vast Mortonian Collection Nor

have I depended upon this Collection alone, as will appear from the

frequent references to and quotations from the more important of the

numerous works which constitute the literature of my subject. This

method has been adopted, as affording the best idea of the past his-

f°ry> progress, and present condition of craniographic research, and

its claims to be considered as one of the natural sciences. By’such

a procedure, moreover, the reader has gradually become acquainted

as it were, with the zealous and indefatigable workers in this field’

whose names are intimately associated with many of the facts discussed

in this essay. Feelings of professional pride prompt me

in this placé, to refer particularly to two of these laborers, who, with

careful hands, have materially assisted in building an Ethnologic

edifice, whose fair proportions will yet delight and astonish the

world. The researches of P richard and M orton constitute right

noble columns guarding the entrance into this edifice. Recognizing,

at an early period of their professional career, the scientific

claims of medicine—claims seldom perceived by the mass—their

expansive minds led them steadily onward, beyond the crowded

middle-walks -of their calling. Both were physiciàns, in the primitive

sense of the word—medical naturalists, whose broad and comprehensive

views shed a lustre over the healing art. There is a

singular propriety in thus coupling the labors and lives of these

two philosophers. Their patient, unresting industiy and strong

determinative will enabled them to prove conclusively to the worlcf

as indeed Hunter and others had already done, that, to a considerable

extent, scientific investigation is not only compatible with the

active daily duties of the physician, but in reality, by inculcating

close and accurate habits of observation, very often becomes a

guarantee of success in the performance of those duties. As confirmatory

of this, hear what their respective biographers have said

of them: “ Dr. Prichard applied himself,” says Dr. Hodgkin, “ with

as much zeal to the practice, as he had done to the study of his

profession. He established a dispensary. He became physician

to some of the principal medical institutions of Bristol. He had not

only a large practice in his own neighborhood, hut was often called to

distant consultations. Notwithstanding the engrossing nature of

these occupations, he found time to prepare and deliver lectures