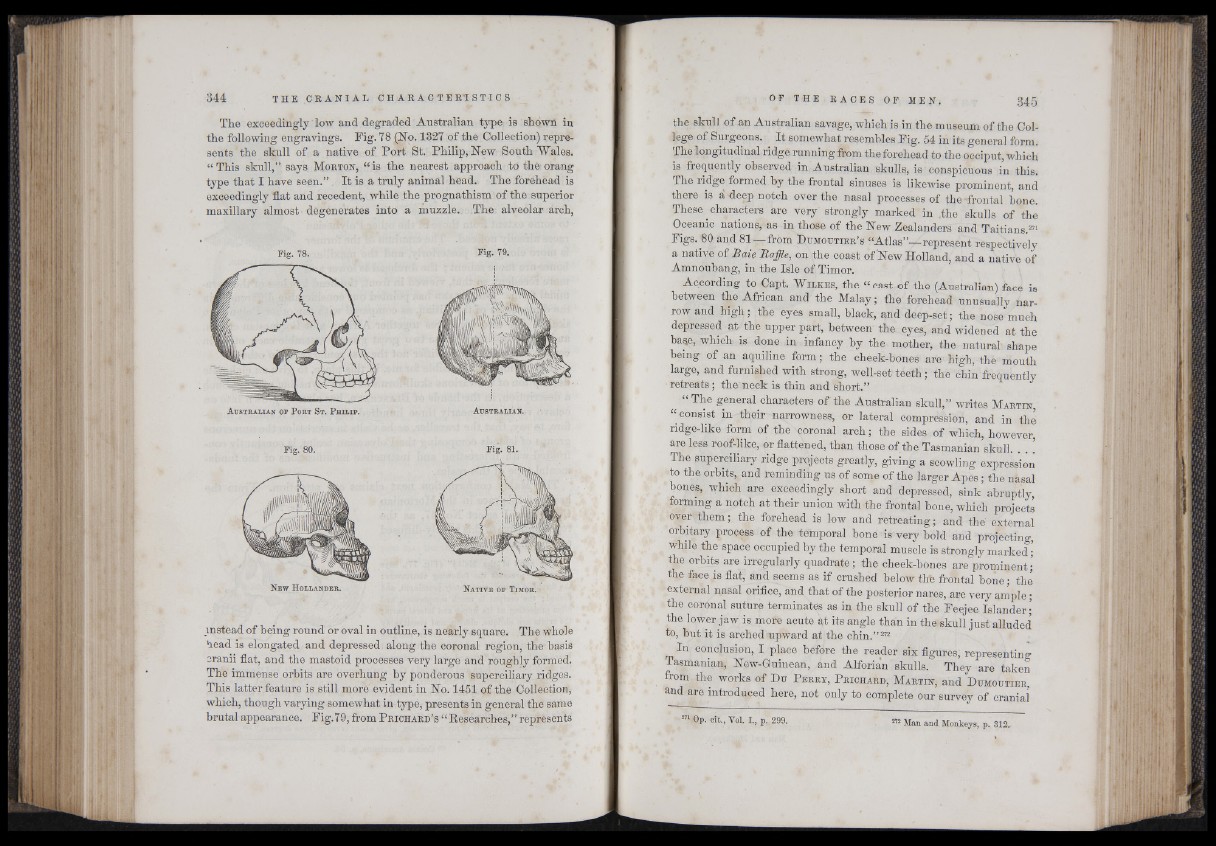

The exceedingly low and degraded Australian type is shown in

the following engravings. Fig. 78 (No. 1327 of the Collection) represents

the skull of a native of Port St. Philip, New South Wales.

“ This skull,” says M orton, “ is the nearest approach to the orang

type that I have seen.” It is a truly animal head. The forehead is

exceedingly flat and recedent, while the prognathism of the superior

maxillary almost degenerates into a muzzle. The alveolar arch,

Fig. 78. Fig. 79.

A u s t r a l ia n o f P o r t S t . P h i l i p . A u s t r a l ia n .

Fig. 80.

N e w H o l l a n d e r . N a t iv e o f T im o r .

.instead of being round or oval in outline, is nearly square. The whole

head is elongated and depressed along the coronal region, the basis

cranii flat, and the mastoid processes very large and roughly formed.

The immense orbits are overhung by ponderous superciliary ridges.

This latter feature is still more evident in No. 1451 of the Collection,

which, though varying somewhat in type, presents in general the same

brutal appearance. Fig.79, from P r ic h a r d ’s “Researches,” represents

the skull of an Australian savage, which is in the museum of the Col-

lege of Surgeons. It somewhat resembles Fig. 54 in its general form.

The longitudinal ridge running from the forehead to the occiput, which

is frequently observed in Australian skulls, is conspicuous in this.

The ridge formed by the frontal sinuses is likewise prominent, and

there is à deep notch over the nasal processes of the -frontal bone.

These characters are very strongly marked in .the skulls of the

Oceanic nations, as in those of the New Zealanders and Taitians.271

Figs. 80 and 81—from D umoutier’s “Atlas”—represent respectively

a native of Baie Raffle, on the coast of'New Holland, and a native of

Amnoubang, in the Isle of Timor.

According to Capt. W il k e s , the “ cast.of the (Australian) face is

between the African and the Malay; the forehead unusually narrow

and high; the eyes small, black, and deep-set; the nose much

depressed at the upper part, between the eyes, and widened at the

ba^e, which , is . done in infancy by the mother, the natural shape

being of an aquiline form; the cheek-bones are high, thè mouth

large, and furnished with strong, well-set teeth ; the chin frequently

■ retreats ; the-neck is thin and short.”

“ The general characters of the Australian skull,” writes M a r t in ,

“ consist in their narrowness, or lateral compression, and in the

ridge-like form of the coronal arch; the sides of which, however

are less roof-like, or flattened, than those of the Tasmanian skull. . . !

The superciliary ridge projects greatly, giving a scowling expression

to the orbits,, and reminding us of some of the larger Apes ; the nasal

bones, which are exceedingly short and depressed, sink abruptly

forming a notch at their union with the frontal bone, which projects

over them; the forehead is low and retreating; and the external

orbitary process of the temporal bone is very bold and projecting,

while the space occupied by the temporal muscle is strongly marked ,’

the orbits are irregularly quadrate; the cheek-bones are prominent;

the face js flat, and seems as if crushed below thb frontal bone ; the

external nasal orifice, and that of the posterior nares, are very ample ;

the coronal suture terminates as in the skull of the Feejee Islander •

the lower jaw is more acute at its angle than in the skull just alluded

to, but it is arched upward at the chin.”272

In conclusion, I place before the reader six figures, representing

Tasmanian, New-Guinean, and Alforian skulls. They are taken

from the works of Du P er ry , P r ich ard, M a r t in , and D umoutiér,

Rnd are introduced here, not only to complete our survey of cranial

271 Op. cit., Vol. I., p. 299. m Man and Monkeys, p. 312.