of the head, as viewed in front, to approximate decidedly to a square. The lateral parts

above the ears are protuberant; the forehead'low; the nose truly aquiline— the curvature

beginning near the top and ending before reaching the point, the base being horizontal;

the chin is round, and the stature short.” 219

Prof. R e t z iu s describes, in the following terms, a “ Schädel eines

römischen Kriegers,” taken from an ancient cemetery at York;

“ This skull is very large, in length as well as in breadth, though of the dolicho-cephalic

(Iranian) form. It is broader above towards the vertex, than below towards the base.

The arch of its upper or coronal surface and the vertex are somewhat flat; the circumference,

seen from above, is 'a long, wedge-like oval, terminating posteriorly in a short,

obtuse angle. Forehead broad, well arched, but rather low; superciliary ridges small;

malar processes of the frontal bone small, not prominent; no frontal protuberances; temples

rounded and projecting; parietal protuberances large, forming lateral angles in a posterior

view, and standing far apart; the semi-circular temporal ridge elevated towards the vertex;

occiput broad, rounded, the protuberance rather prominent ; the sagittal suture slightly

depressed, especially in the posterior part; receptaculum cerebelli large, &c.” 220

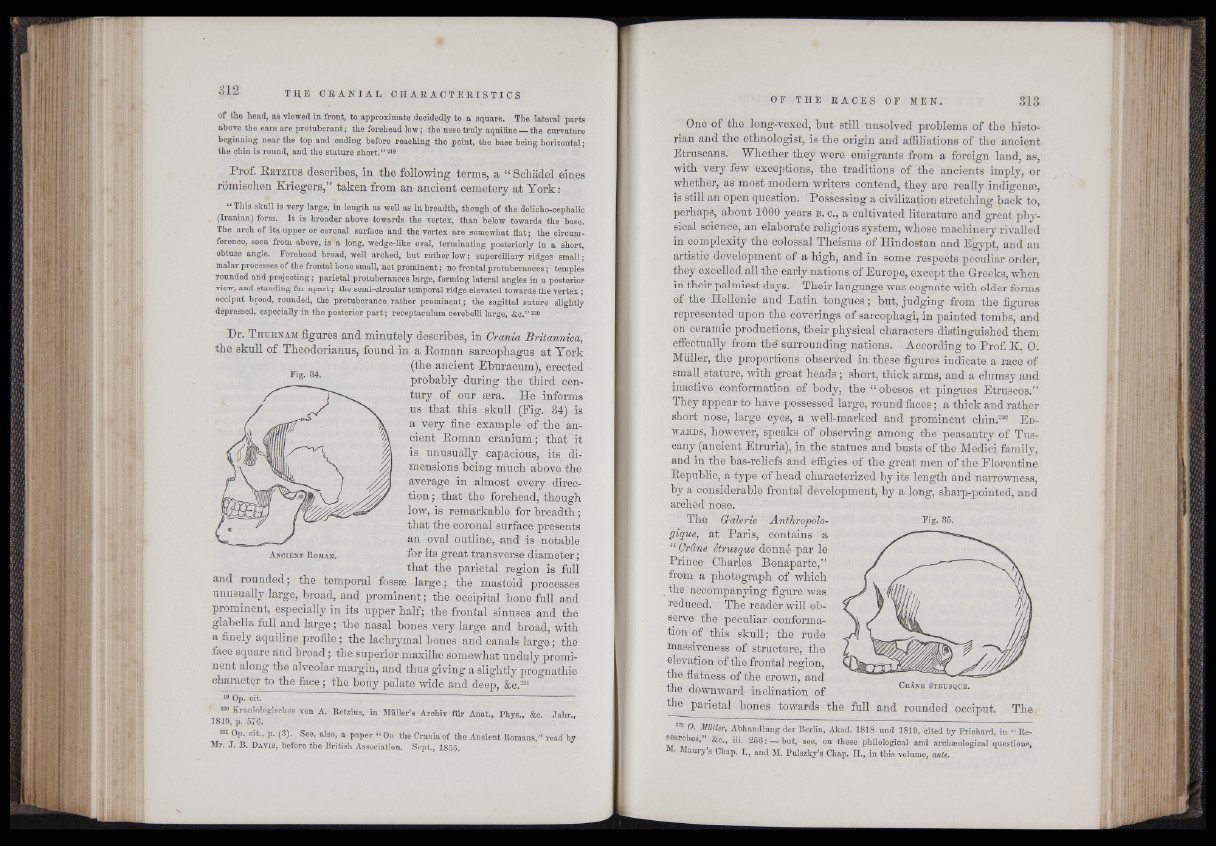

Dr. T hurnam figures and minutely describes, in Crania Britannica,

the skull of Theodorianus, found in a Roman sarcophagus at York

(the ancient Eburacum), erected

probably during the third century

of our sera. He informs

us that this skull (Pig. 34) is

a very fine example of the ancient

Roman cranium; that it

is unusually capacious, its dimensions

being much above the

average in almost every direction;

that the forehead, though

low, is remarkable for breadth;

that the coronal surface presents

an oval outline, and is notable

for its great transverse diameter;

that the parietal region is full

Fig. 34.

A n c ie n t R oman .

and rounded; the temporal fossse large; the mastoid processes

unusually large, broad, and prominent; the occipital bone full and

prominent, especially in its upper half; the frontal sinuses and the

glabella full and large; the nasal bones very large and broad, with

a finely aquiline profile; the lachrymal bones and canals large; the

face square and broad; the superior maxill® somewhat unduly prominent

along the alveolar margin, and thus giving a slightly prognathic

character to the face; the bony palate wide and deep, &c.m

19 Op. cit. " " ~ | ¡j ~ : _

220 Nraniologisches von A. Retzius, in Müller’s Archiv für Anat., Phys., &c. Jahr.,

1849, p. 576. J ’

m Op. cit., p. (3). See, also, a paper “ On the Crania of the Ancient Romans,” read by

Mr. J . B. Da v is , before the British Association. Sept., 1855.

One of the long-vexed, but still unsolved problems of the historian

and the ethnologist, is the origin and affiliations of the ancient

Etruscans. Whether they were emigrants from a foreign land, as,

with very few exceptions, the traditions of the ancients imply, or

whether, as most modern writers contend, they are really indigense,

is still an open question. Possessing a civilization stretching back to,

perhaps, about 10 0 0 years b . c., a cultivated literature and great physical

science, an elaborate religious system, whose machinery rivalled

in complexity the colossal Theisms of Hindostan and Egypt, and an

artistic development of a high, and in some respects peculiar order,

they excelled all the early nations of Europe, except the Greeks, when

in their palmiest days. Their language was cognate with older forms

of the Hellenic and Latin tongues ; but, judging from the figures

represented upon the coverings of sarcophagi, in painted tombs, and

on ceramic productions, their physical characters distinguished them

effectually from the' surrounding nations. According to Prof. K. 0.

Müller, the proportions observed in these figures indicate a race of

small stature, with great heads ; short, thick arms, and a clumsy and

inactive conformation of body, the “ obesos et pingues Etruseos.”

They appear to have possessed large, round faces ; a thick and rather

short nose, large eyes, a well-marked and prominent chin.2*3 E dwards,

however, speaks of observing among the peasantry of Tuscany

(ancient Etruria), in the statues and busts of the Medici family,

and in the bas-reliefs and effigies of the great men of the Florentine

Republic, a type of head characterized by its length and narrowness,

by a considerable frontal development, by a long, sharp-pointed, and

arched nose.

The Galerie Anthropolo- IjSfj 35.

gique, at Paris, contains a

“ Crâne étrusque donné par le

Prince Charles Bonaparte,”

from a photograph of which

the accompanying figure was

reduced. The reader,will observe

the peculiar conforma^

tion of this skull; the rude

massiveness of structure, the

elevation of the frontal region,

the flatness of the crown, and

the downward inclination of C e a n e é t e u s q u e .

the parietal bones towards the full and rounded occiput. The

222 Abhandlung der Berlin, Akad. 1818 und 1819, cited by Prichard, in “ Re-

6arc eé, &c., iii. 256 : — but, see, on these philological and archaeological question**,

• Maury’s Chap. I., and M. Pulszky’s Chap. n ., in this volume, ante.