was in Egypt never emancipated from architecture.53 It was sculptured

for a certain and determinate place, always in connection with

a temple, palace, or sepulchre, of which it became a subservient

ornamental portion, an architectural member as it were, like the pair

of obelisks placed ever in front of the propyleia, or the columns supporting

a pronaos. This poverty of forms, and their constantly

recurring monotony, make the inspection of large Egyptian collections

as tiresome to the great bulk of visitors, as the review of a

Russian regiment is to the civilian; one figure resembles the other,

and only the closer investigation of an experienced eye' descries a

difference of style and individuality.

The bas-reliefs were not, for the Egyptians, so much independent

works of art, as architectural ornaments, and means for conveying

knowledge, answering often the purpose of a kind of vignettes or

illustrations of hieroglyphical inscriptions. They record always some

defined, historical, religious, or domestic scene, without pretension

to any allegorical double-meaning, or esoteric symbolism. Beauty

remained with their hierogrammatic artists less important than distinctness,

the correctness of drawing being sacrificed to conventionalisms

of hieratic s ty leb u t, on the other hand, a general truthfulness

of the representation was peculiarly aimed at. The unnatural

mannerism of the Egyptian bas-relief manifests itself principally in

the too high position of the ear,54 and in representing the eye and

chest as in front view, whilst the head and lower part of the body are

drawn in profile.55 nevertheless, this constant mannerism and many

occasional incorrectnesses are blended with the most minute appreciation

of individual and national character. It is impossible not at

once to recognize the portraits of the kings upon their different

monuments; and we- alight on reliefs where some of the figures are

so carelessly drawn as to present two right or two left hands to the

spectator, yet combined with such characteristic effigies of negroes, of

Shemites, of Assyrians, of Nubians, &c., that they remain superior to

the representations of human races by the. Greeks and Romans.

This general truthfulness applies to Egyptian art from the very first

dawn of history, throughout all the subsequent periods, down to the

time of the Roman conquest. But whilst the principal features of

art remained stationary,' the eye of the art-student finds many

changes in details, and these constitute the history of Egyptian art.

53 Cf. W i l k i n s o n , Architecture of the Ancient Egyptians, London, 1853.

54 Morton, Cran. JEgypU^VhiifoA., 1844, pp. 26-7; and “ inedited MSS.” in Types of Mankind,

p. 318:— P r u n e r , Die JJeberbleibsel der AItagyptishchenMenschenrage,München,184:6,

55 For a ludicrous example, see the “ 37 Prisoners at Bonihassan,” in RosELLiNij M. R.

XXYI—VIII; of the remote age of the Xllth dynasty.

The proportions of the statues in the time of the Old Empire [say

from the 35th century b . c., down to the 20th,56] are short and heavy;

the figures look, therefore, somewhat awkward; but, on the whole,

they are conceived with considerable feeling of truth, and executed

with the endeavour to obtain anatomical correctness. The principal

forms of the body, and even its details, the skull, the muscles of the

chest and of the knees, are nearly always correctly sculptured in close

but not servile imitation of nature. The shape of the eye is not yet

disfigured by a conventional frame, nor is the ear put too high; but

the fingers and toes evidently offered the greatest difficulties to the

primeval Egyptian artists. They commonly failed to form them

correctly; the simplicity and exactitude displayed in sculpturing the

face and body scarcely ever extended to the hands and feet, which

are blunt and awkward.

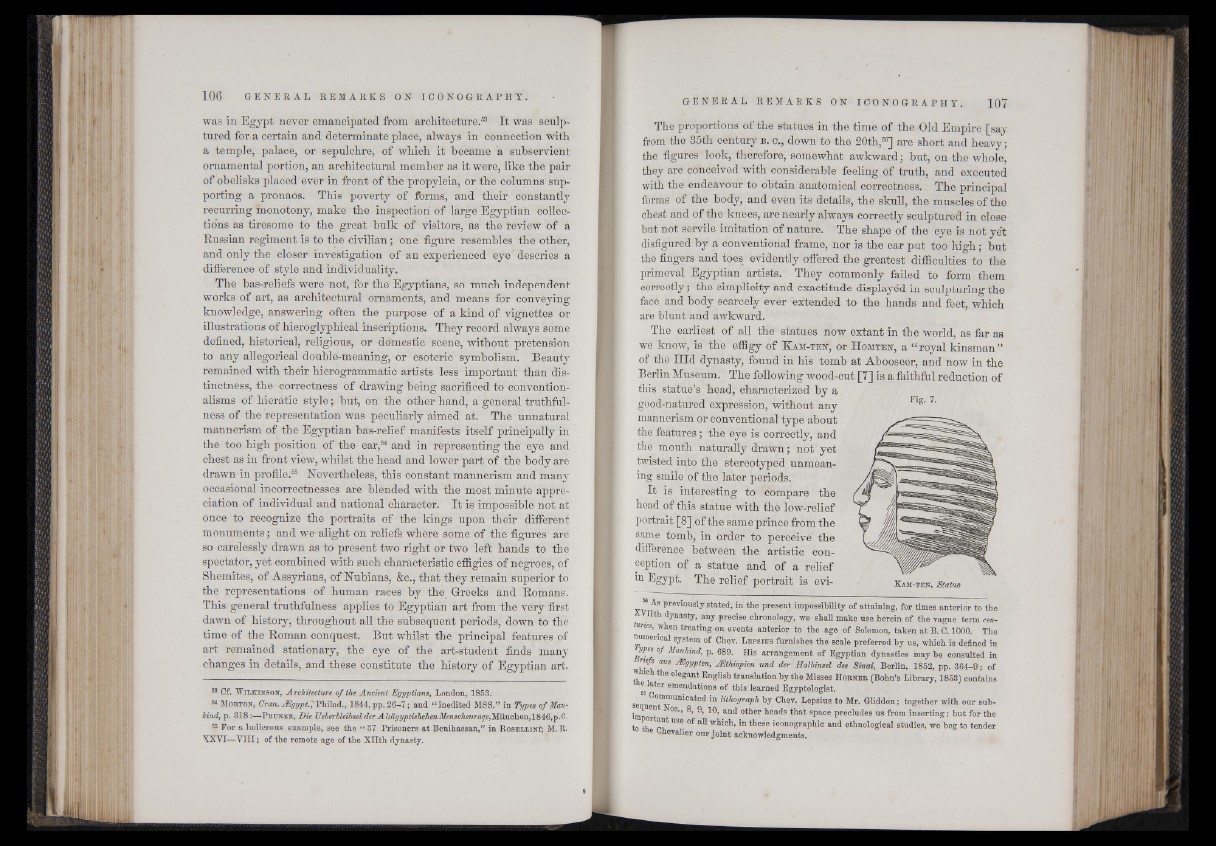

The earliest of all the statues now extant in the world, as far as

we know, is the effigy of K am -t e n , or H omten, a “royal kinsman”

of the Bid dynasty, found in his tomb at Abooseer, and now in the

Berlin Museum. The following wood-cut [7] is a faithful reduction of

this statue’s head, characterized by a

good-natured expression, without any

mannerism or conventional -type about

the features; the eye is correctly, and

the mouth naturally drawn; not yet

twisted into the stereotyped unmeaning

smile of the later periods.

It is interesting to compare the

head of this statue with the low-relief

portrait [8] of the same prince from the

same tomb, in order to perceive the

difference between the artistic conception

of a statue and of a relief

in Egypt. The relief portrait is evi-

XVTf 8 PreT1<rasly stated, in the present impossibility of attaining, for times anterior to the

Uth dynasty, any precise chronology, we shall make use herein of the vague term centuries,

when treating on events anterior to the age of Solomon, taken at B. C. 1000. The

numerical system of Chev. L e p s iv s furnishes the scale preferred by us, which is defined in

Wes of Mankind, p. 689. His arrangement of Egyptian dynasties inay be consulted in

wh* h aUS ^'9yptm’ '!thioPitn und der ffalbinsel dee Sinai, Berlin, 1852, pp. 364—9 ; of

* ic the elegant English translation by the Misses H o r n e r (Bohn’s Library, 1853) contains

® ater emendations of this learned Egyptologist.

seque *n lithograph by Chev. Lepsius to Mr. Gliddon; together with our subiniD

^ °S’’ an<^ ° ^ er heads that space precludes us from inserting; but for the

to th* nT USe. °f a11 Which’ in these icon°graphic and ethnological studies, we beg to tender

e hevalier our joint acknowledgments.

Fig. 7.