entre leu os jugaux à leur insertion, qu’elle est manifestement supérieure à celle que nous

avons reconnue sur de nombreux crânes de naturels des îles Marquises. Cette différence

est aussi très-sensible dans le crâne d’enfant qui, sur la même planche, porte les numéros

6 et 6.”

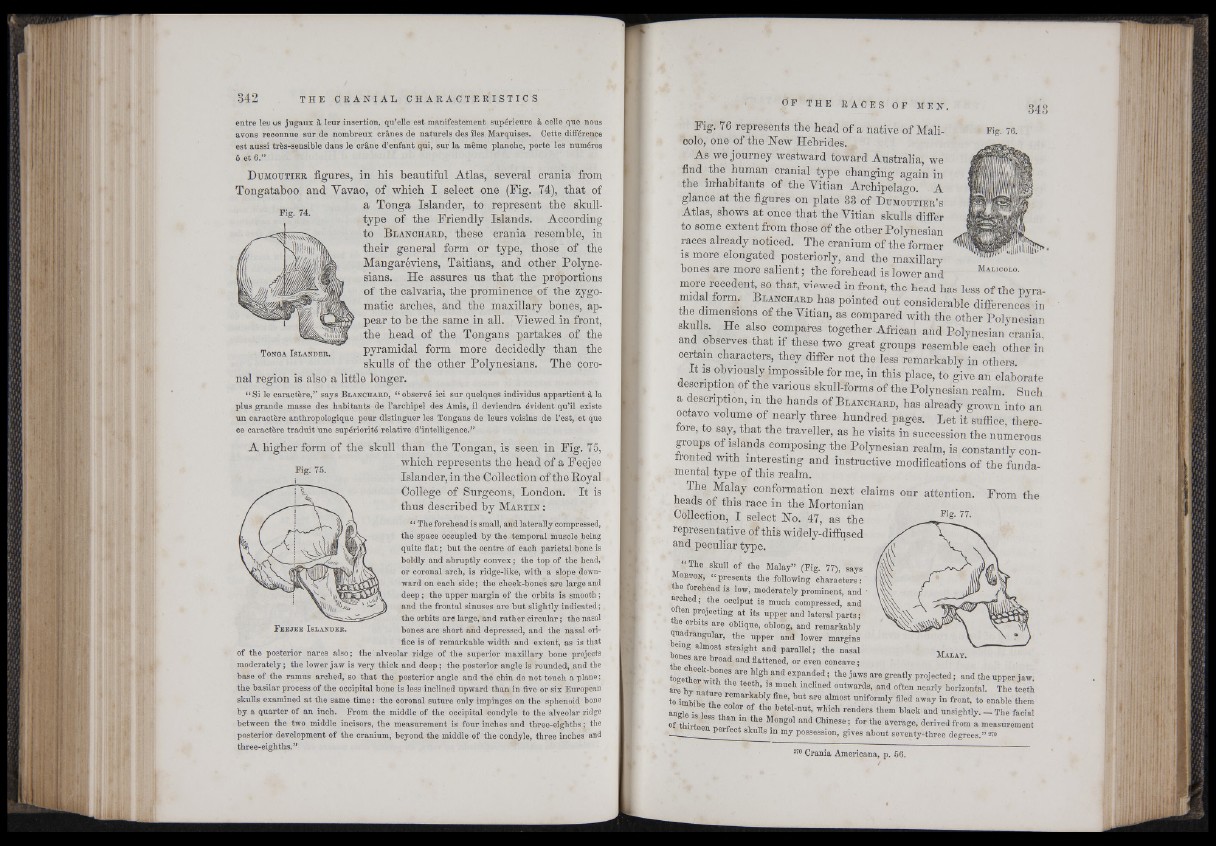

D umoutier figures, in his beautiful Atlas, several crania from

Tongataboo and Vavao, of which I select one (Fig. 74), that of

Fig. 74.

T o n g a I s l a n d e r .

a Tonga Islander, to represent the skull-

type of the Friendly Islands. According

to B lanchard, these crania resemble, in

their general form or type, those of the

Mangaréviens, Taitians, and other Polynesians.

He assures us that the proportions

of the calvaria, the prominence of the zygomatic

arches, and the maxillary bones, appear

to he the same in all. Viewed in front,

the head of the Tongans partakes of the

pyramidal form more decidedly than the

skulls of the other Polynesians. The coronal

region is also a little longer.

“ Si le caractère,” says B l a n c h a r d , “ observé ici sur quelques individus appartient à la

plus grande masse des habitants de l’archipel des Amis, il deviendra évident qu’il existe

un caractère anthropologique pour distinguer les Tongans de leurs voisins de l’est, et que

ce caractère traduit une supériorité relative d’intelligence.

A higher form of the skull than the Tongan, is seen in Fig. 75,

which represents the head of a Feejee

Islander, in the Collection of the Royal

College of Surgeons, London. It is

thus described by M a r t in :

“ The forehead is small, and laterally compressed,

the space occupied by the temporal muscle being

quite flat ; but the centre of each parietal bone is

boldly and abruptly convex ; the top of the head,

or coronal arch, is ridge-like, with a slope downward

on each side ; the cheek-bones are large and

deep ; the upper margin of the orbits is smooth ;

and the frontal sinuses are but slightly indicated ;

the orbits are large, and rather circular ; the nasal

bones are short and depressed, and the nasal orifice

is of remarkable width and extent, as is that

Fig; 75.

A

ü

F e e j e e I s l a n d e r .

of the posterior nares also ; the alveolar ridge of the superior maxillary bone projects

moderately ; the lower jaw is very thick and deep ; the posterior angle is rounded, and the

base of the ramus arched, so that the posterior angle and the chin do not touch a plane ;

the basilar process of the occipital bone is less inclined upward than in five or six European

skulls examined at the same time : the coronal suture only impinges on the sphenoid bone

by a quarter of an inch. From the middle of the occipital condyle to the alveolar ridge

between the two middle incisors, the measurement is four inches and three-eighths ; the

posterior development of the cranium, beyond the middle of the condyle, three inches and

three-eighths.”

Fig. 76 represents the head of a native of Mali-

oolo, one of the New Hebrides.

As we journey westward toward Australia, we

find the human cranial type changing again in

the inhabitants of the Vitian Archipelago. A

glance at the figures on plate 33 of D umo u tier’s

Atlas, shows at once that the Vitian skulls differ

to some extent from those of the other Polynesian

races already noticed. The cranium of the former

is more elongated posteriorly, and the maxillary

bones are more salient; the forehead is lower and Mal,colo-

more recedent so that, viewed in front, the head has less of the pyramidal

form. B lanchard has pointed out considerable differences in

the dimensions of the Vitian, as compared with the other Polynesian

skulls He also compares together African and Polynesian crania

and observes that if these two great groups resemble each other in

certain characters, they differ not the less remarkably in others

It is obviously impossible for me, in this place, to give an elaborate

description of the various skull-forms of the Polynesian realm. Such

a description, m the hands of B lanchard, has already grown into an

octavo volume of nearly three hundred pages. Let it suffice, therefore,

to say that the traveller, as he visits in succession the numerous

groups of islands composing the Polynesian realm, is constantly confronted

with interesting and instructive modifications of the fundamental

type pf this realm.

The Malay conformation next claims our attention. From the

ncads of this race in the Mortonian

Cqllection, I select No. 47, as the

representative of this widely-diffused

and peculiar type.

“ The skull of the Malay” (Fig. 77), says

M o b to n , “ presents the following characters:

tie forehead is low, moderately prominent, and i

arched, the occiput is much compressed, and

often projecting at its upper and lateral parts;

e orbits are oblique, oblong, and remarkably

quadrangular, the upper and lower margins

being almost straight and parallel; the nasal

ones are broad and flattened, or even concave;

M a l a y .

together witlTrt T exPanded 5 4116 Jaws are greatly projected; and the upper jaw,

are bv n » T i “ mUCh in°Hned ontwards’ and often “ arly horizontal. The teeth

to i m L f r re,markab’y but “ O almost uniformly filed away in front, to enable them

angle is less th™ " *be betel-nut' wHcb renders them black and unsightly. - The facial

of thirteen n e r f iT t\ I ngo1 and Cblnese ’ forthe average, derived from a measurement

—_ Perfect skulls id m y possession, gives about seventy^three degrees.” 2™

270 Crania Americana, p. 56.