added to the head to designate Demetrius as the son of Neptune;

whilst in order to combine the horn with the human features, the hair

was carved stiff, reminding one of the rigidity of a hull’s hair.

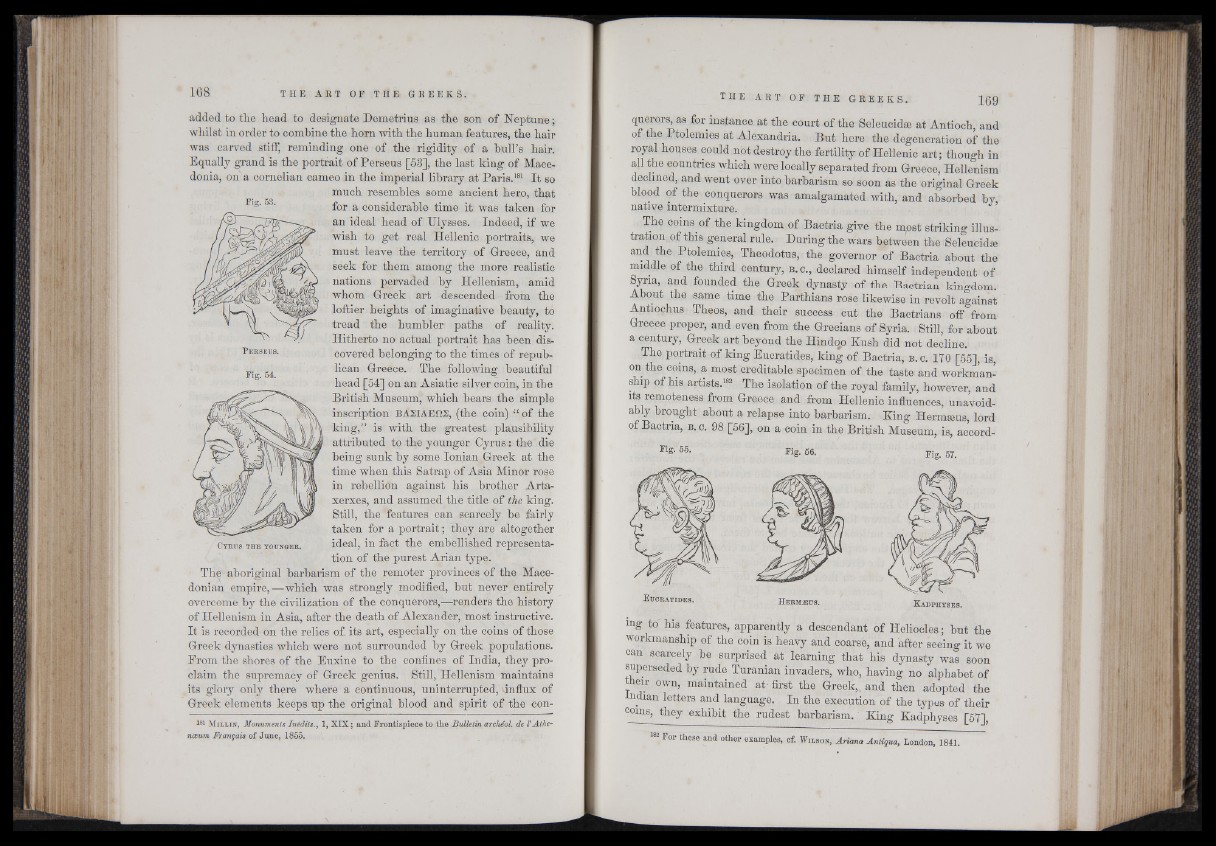

Equally grand is the portrait of Perseus [53], the last king of Macedonia,

on a cornelian cameo in the imperial library at Paris.181 It so

much resembles some ancient hero, that

for a considerable time it was taken for

an ideal head of Ulysses. Indeed, if we

wish to get real Hellenic portraits, we

must leave the territory of Greece, and

seek for them among the more realistic

nations pervaded by Hellenism, amid

whom Greek art descended from the

loftier heights of imaginative beauty, to

tread the humbler paths of reality.

Hitherto no actual portrait has been discovered

belonging to the times of republican

Greece. The following beautiful

head [54] on an Asiatic silver coin, in the

British Museum, which bears the simple

inscription BA 2 lA E fi2 , (the coin) “ of the

■king,” is with the greatest plausibility

attributed to the younger Cyrus : the die

being sunk by some Ionian, Greek at the

time when this Satrap of Asia Minor rose

in rebellion against his brother Arta-

xerxes, and assumed the title of the king.

Still, the features can scarcely be fairly

taken for a portrait; they are altogether

ideal, in fact the embellished representation

of the purest Arian type.

Fig. 53.

Fig. 54.

The’ aboriginal barbarism of the remoter provinces of the Macedonian

empire,—which was strongly modified, but never entirely

overcome by the civilization of the conquerors,—renders the history

of Hellenism in Asia, after the death of Alexander, most instructive.

It is recorded on the relies of its art, especially on. the coins of those

Greek dynasties which were not surrounded by Greek populations.

From the shores of the Euxine to the confines of India, they proclaim

the supremacy of Greek genius. Still, Hellenism maintains

its glory only there where a continuous, uninterrupted, finflux of

Greek elements keeps up the original blood and spirit of the con-

181 M i l l i n , Monuments Inédits., 1, XIX; and Frontispiece to the Bulletin archéol. de VAthenaeum

Français of June, 1855.

querors, as for instance at the court of the Seleucid® at Antioch, and

of the Ptolemies at Alexandria. But here the degeneration of the

royal houses could not destroy the fertility of Hellenic art; though in

all the countries which were locally separated from Greece, Hellenism

declined, and went over into barbarism so soon as the original Greek

blood of the conquerors was amalgamated with, and absorbed by

native intermixture.

The coins of the kingdom of Bactria give the most striking illustration

of this general rule. During the wars between the Seleucidee

and the Ptolemies, Theodotus, the governor of Bactria about the

middle:of the third century, B.C., declared himself independent of

Syria, and founded the Greek dynasty of the Bactrian kingdom.

About the same time the Parthians rose likewise in revolt against

Antiochus Theos, and their success cut the Bactrians off from

Greece proper, and even from the Grecians of Syria. Still, for about

a century, Greek art beyond the Ilindqo Kush did not decline.

The portrait of king Eucratides, king of Bactria, b . c. 170 [55], is,

on the coins, a most creditable specimen of the taste and workmanship

of his. artists.182 The isolation of the royal fanfily, however, and

its remoteness from Greece and from Hellenic influences, unavoidably

brought about a relapse into barbarism. King Hermseus, lord

of Bactria, b . c. 98 [56], on a coin in the British Museum; is, aecord-

Fis- 55 Fig. 56. Fig<57t

mg to' his features, apparently a descendant of Heliocles; but the

workmanship of the coin is heavy and coarse, and after seeing it we

can scarcely be surprised at learning that his dynasty was soon

superseded by rude Turanian invaders, who, having no alphabet of

eir own, maintained at' first the Greek,, and then adopted the

Indian letters and language. In the execution of the types of their

coins, they exhibit the rudest barbarism. King Kadphyses [57],

182 For these and other examples, o f. W i l s o n , Ariana Anliqua, London, 1841.