162 T H E A R T OP T H E G R E E K S .

and Babylon, we must still admit the early influence of Egyptian (Saitic)

and oriental art over Greece. A peculiar school of ancient sculpture,

to which the invention of casting statues is attributed, developed

itself in the island of Samos between the 30th1 and 55th Olympiad

(657-557 b . c.) extending from the time of Psammeticus of Egypt

to the epoch of Croesus of Lydia, and Cyrus of Persia; and history

contains many evidences of the intercourse of the Samians with the

kings of Egypt and Lydia, and with the merchants of Phoenicia.

The types of the coins of Samos,—the lion’s head and bull’s head,—

are similar to the Assyrian representations. As to the Egyptian

influence, Steinbiichel justly lays peculiar stress upon the rude archaic

type of the silver coins of Athens with the helmeted head of Minerva,

which was persistently retained by the republic even in the times of

her highest artistical eminence. It certainly shows the eye, represented

in the Egyptian front-view, whilst the angle of the lips is

raised, and smiles in the later pharaonic manner. All the earliest

coins and bas-reliefs of Greece are characterized by the same peculiarity,

and some of them retained even the Egyptian head-dress in

slightly modified forms. The anecdote preserved by Diodorus

biculus, concerning Telecles and Theodoras of Samos,(who are said

to have made a bronze statue in two halves, independently of one

another, which upon being joined were found to agree perfectly),was

likewise explained by the invariable rales of the Egyptian canon;167

though, according to our views, it has nothing to do with Egypt, and

owes its origin probably to the traces of chiselling that removed

the seam of the cast all along the figure, and which being of a different

color from the unchiselled surface of the statue, was mistaken

for ancient soldering. '

The indubitable connexion of Greece with Egypt, under the Saite

dynasty, could not fail to have great influence on art. The Greeks

gained from that quarter their acquaintance with the different

mechanical processes of sculpture, carving, moulding, casting, and

chiselling. though, too proud to acknowledge their debt to foreigners,

they attributed the invention of the saw and file, drill and rule, to

the mythical Cretan Daedalus, or to the Samian Theodoras, the

elder, at any rate, to artists natives of the Archipelago in proximity

with Egypt. It seems, indeed, that the opening of Egypt gave a sudden

impulse to sculpture and painting among the Hellenes: for nearly

all the earliest works mentioned by the ancients belong to^this period,

with the exception, perhaps, of the casket of C ypselos, and of the

Diodob., i, 98:—60 f. Mülusb, Archéologie, § 70, 4.

t h e a r t o p t h e G r e e k s . 163

w utHucmea oy uypseios at Olympia.168 The

athletic statues of A r r h a c h io n 169 (53 Olympiad), P r a x id am a s (58

- ^ x m o s (Si 01.), at Olympia, of C l eo bis and B iton, at

fw W ( 01.), of H armo dius and A risto geiton, at Athens

(67 01.), all works of the Samian school, (and among them the

works of art dedicated by Alyattes and Croesus to the Delphian

temple), were the result of the intercourse with Egypt: and, from the

description of some of them, as for instance, the statue of Arrhaehion

we see that their rigid attitude must have resembled the Egyptian

statues. Still, whatever be the foreign influences on the beginnings

of Greek art, nobody will ever take the most archaic Greek relief for

a specimen of Egyptian or Assyrian art. Though such Greek rudiments

are less elaborate than the royal works of Thebes, Nineveh, or

Persepohs, they have a peculiar national style unmistakably Greek.

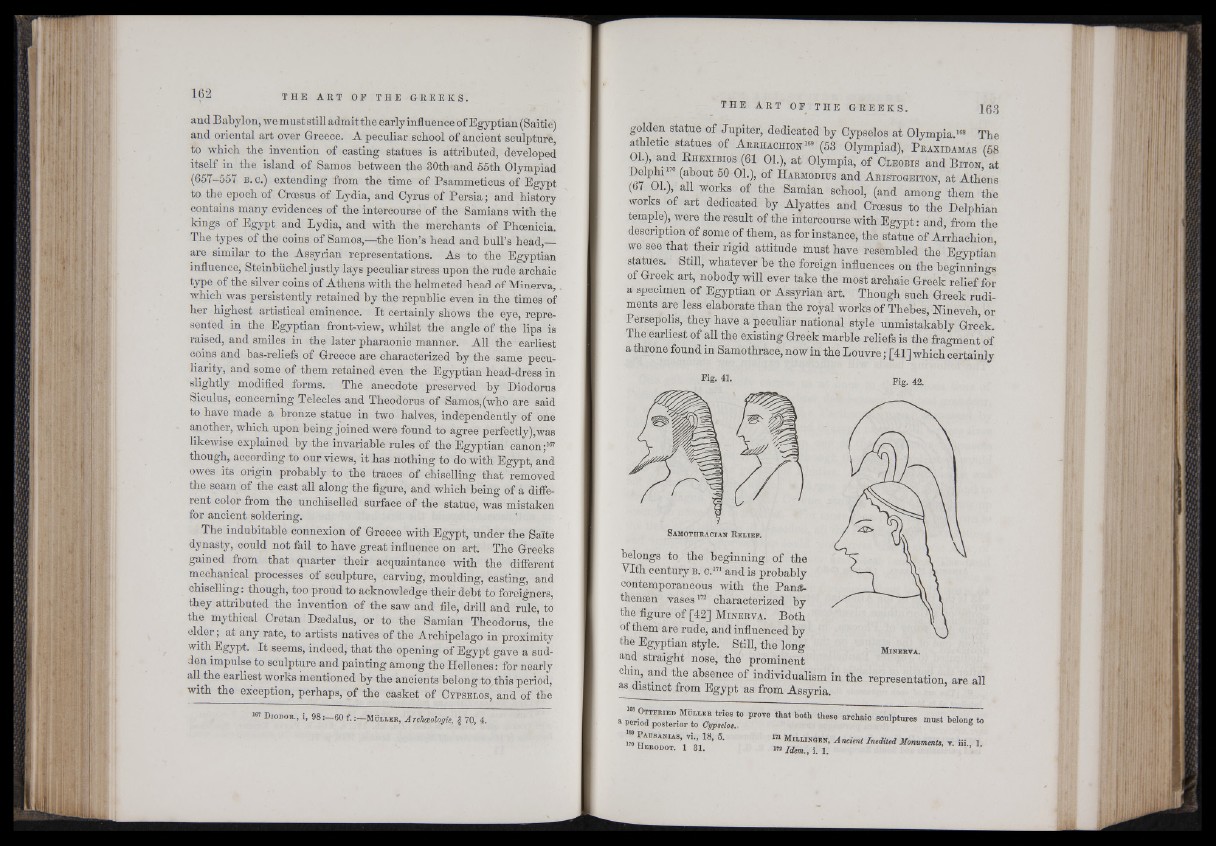

The earliest of all the existing Greek marble reliefs is the fragment of

a throne found in Samothrace, now in the Louvre ; [41] which certainly

Fig. 41. Fig. 42.

belongs to the beginning of the

Vlth century b . c.m andis probably

contemporaneous with the PaniJ-

thenæn vases172 characterized by

the figure of [42] M in e r v a . Both

of them are rude, and influenced by

the Egyptian style. Still, the long

and straight nose, thé prominent

chin, and the absence of individualism in the representation, are all

as distinct from Egypt as from Assyria.

prove thatboth these arohaio

S f f l E f f P 5- - i«., i.