and of all the countries of Asia Minor, differ little from the monuments

of Greece proper.

The type of the Sicilians and of the Italiots is somewhat more

diverse ; principally characterized by the full and round chin of the

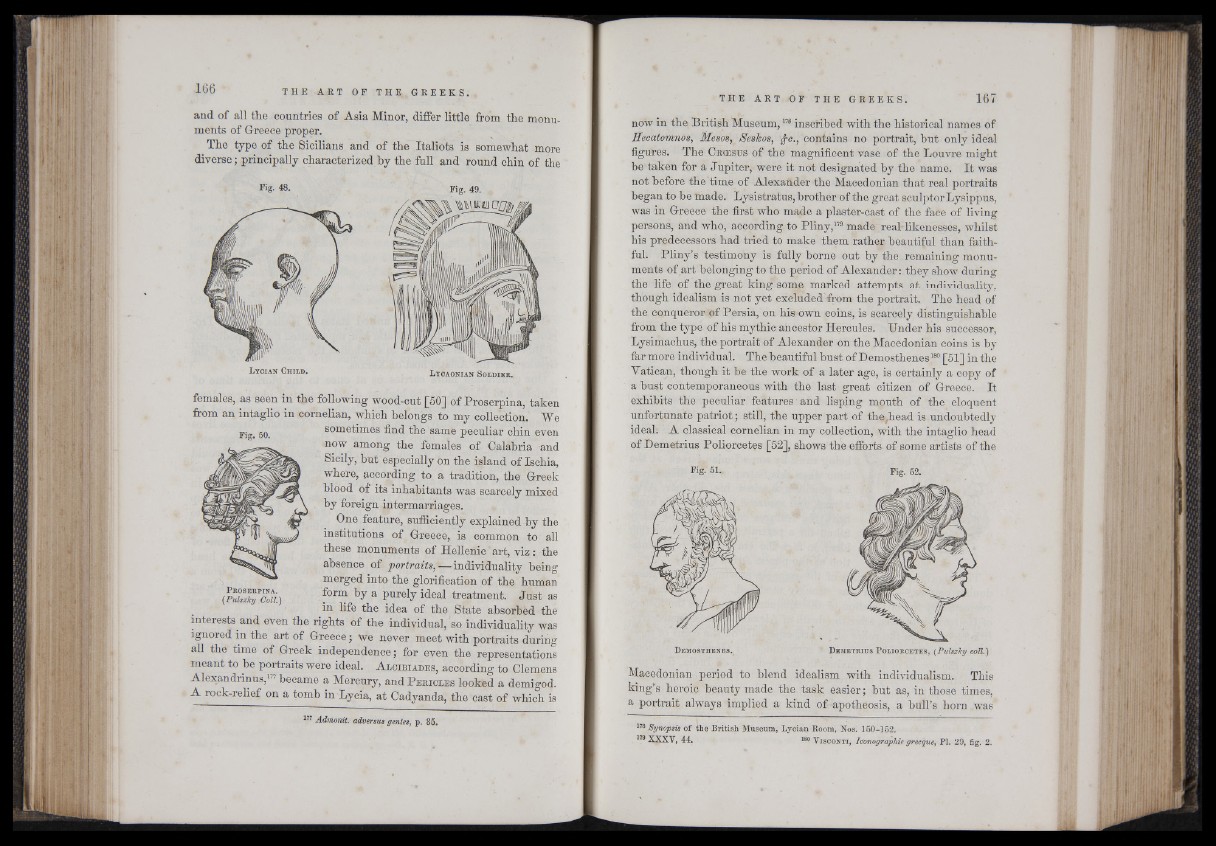

Fig- 48. Fig. 49.

L y c ia n C h i l d . Lïcaonian S oldier.

females, as seen in the following wood-cut [50] of Proserpina, taken

from an intaglio in eornelian, which belongs to my collection. We

50 sometimes find the same peculiar chin even

now among the females of Calabria and

Sicily, but especially on the island of Ischia,

where, according to a tradition, the Greek

blood of its inhabitants was scarcely mixed

by foreign intermarriages.

One feature, sufficiently explained by the

institutions of Greece, is common to all

these monuments of Hellenic art, v iz : the

absence of portraits,—individuality being

merged into the glorification of the human

)' f°rm by a Purely ideal treatment. Just as

in life the idea of the State absorbed the

interests and even the rights of the individual, so individuality was

ignored in the art of Greece; we never meet with portraits during

all the time of Greek independence; for even the representations

meant to be portraits were ideal. A l c ib ia d e s , according to Clemens

Alexandrinus,177 became a Mercury, and P e ricl es looked a demigod.

A rock-relief on a tomb in Lycia, at Cadyanda, the cast of which is

177 Admonit. adversus g entes, p. 35.

now in the British Museum, 178 inscribed with the historical names of

Secatomnos, Mesos, SesJcos, ¿•c., contains no portrait, but only ideal

figures. The Crcesus of the magnificent vase of the Louvre might

be taken for a Jupiter, were it not designated by the name. It was

not before the time of Alexander the Macedonian that real portraits

began to be made. Lysistratus, brother of the great sculptor Lysippus,

was in Greece the first who made a plaster-cast of the face of living

persons, and who, according to Pliny,179 made reablikenesses, whilst

his predecessors had tried to make them rather beautiful than faithful.

Pliny’s testimony is fully borne out by the remaining monuments

of art belonging to the period of Alexander: they show during

the life of the great king some marked attempts at individuality,

though idealism is not yet excluded from the portrait. The head of

the conqueron of Persia, on his own coins, is scarcely distinguishable

from the type of his mythic ancestor Hercules. Under his successor,

Lysimaehus, the portrait of Alexander on the Macedonian coins is by

far more individual. The beautiful bust of Demosthenes180 [51] in the

Vatican, though it be the work of a later age, is certainly a copy of

a bust contemporaneous with the last great citizen of Greece. It

exhibits the peculiar features.- and lisping mouth of the_ eloquent

unfortunate patriot; still, the upper part of theyhead is undoubtedly

ideal. A classical cornelian in my collection, with the intaglio head

of Demetrius Poliorcetqs [52], shows the efforts of some artists of the

Fig. 61* Fig. 52.

Demosthenes. Demetrius P oliorcetes, (PulszTcy coll.)

Macedonian period to blend idealism with individualism. This

king’s heroic beauty made the task easier; but as, in those times,

a portrait always implied a kind of-apotheosis, a bull’s horn was

178 Synopsis of the British Muséum, Lycian Room, Nos. 150-152.

179 XXX.Y, 44. 189 Visconti, Iconographie grecque, Pl. 29, fig. 2.