because, having been found at Pompeii together with the bust of

Scipio Africanus, it might have been its companion. He discovers

an African cast in the features of the bust, although he does not

enable us to understand what African peculiarity he means; and he

forgets that Hannibal ought to portray the true Shemitic, not any

African type. Visconti refers likewise to the peculiar head-dress of

the bust, as being analogous to that of king Juba; but Juba was a

Humidian, (inheriting some Berber blood, probably,) not a Carthaginian

by lineage; and the resemblance is altogether imaginary.

Lastly, he identifies the features of the bronze with those of a fine

bearded and helmeted head often found on gems,27 and traditionally

ascribed to Hannibal, because one of the copies bears evidently the

half-effaced inscription HA. . .BA. .28 Unfortunately for Visconti,

the gems and the bronze bust have not one single feature in common

between them; and we are even able to trace the origin of the tradition

and of the inscription mentioned by the renowned author of the

“ Iconographie ”—to a rather modem date. There exists a celebrated

colossal marble statue in the ante-room of the Capitoline Museum,

which had always puzzled antiquaries. It represents a bearded

warrior, with a stern and majestic countenance; and would have

been taken for Mars, did we not know, that all the statues of the god

of war, with the exception of the earliest archaic representations,

were beardless. Another designation was therefore wanted; and

inasmuch as among the adornments of the magnificent armour of

the colossus, two elephant heads occupy a prominent place, he was

called Pyrrhus, and sometimes Hannibal,—both generals having

made use of elephants in their wars against Rome. The gems mentioned

by Visconti are evidently antique-copies of the head of the

Capitoline statue, from which they obtained the name. As to the

inscription of the Florentine gem mentioned by Gori, we can a ffirm

that it is a mediaeval forgery; because, on another repetition of the

same head,29 we find an analogous imposition, viz: the same Phoenician

letters which are struck on the Cilician coins of Datames, and

were transferred from the medal to the gem by some mediaeval

engraver under the (false) belief that they read: “Hannibal.” Besides,—

the Capitoline statue and the gems resembling it are no portraits

at all, they have ideal features, and represent Zeus Areios, the

martial Jupiter, as beheld on the coins of the town Iasus in Caria,30

v G o r i. M us. Flor., 11, 12. 38 G o r i, Inscriptions p e r Elrur., 1 pi. 10, p. 4.

■ W in c k k lm a n n , Pierres gravies du feu Baron Sloseh, p. 415, nos. 43:—R a s p e , Catalogue

p. 559, No. 9598.

” Streber, Abhandl. der philologischen Classe, der Münchner Academic, Theil 1, Tafel 4,

No. 6.

no less than on several unpublished bronze statuettes in different

collections.

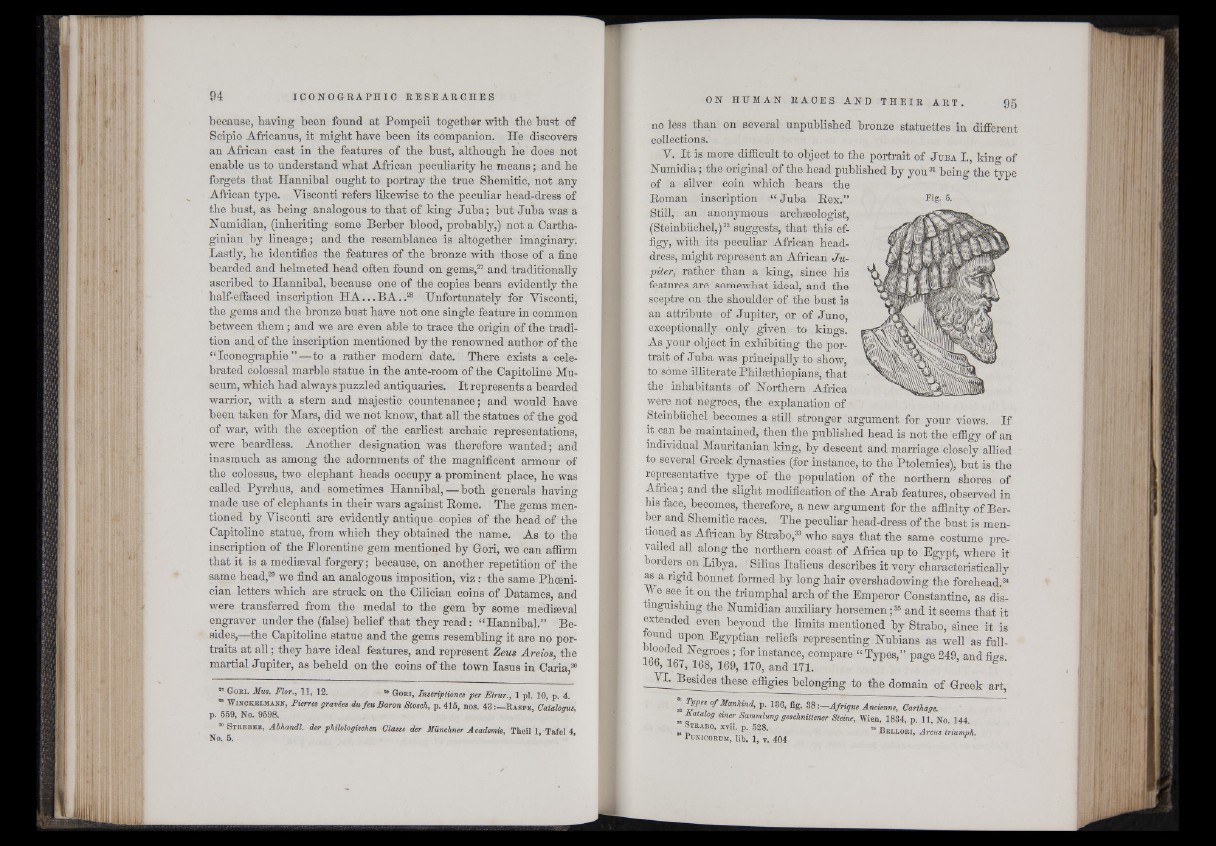

V. It is more difficult to object to the portrait of J uba I., king of

Uumidia; the original of the head published by you31 being the type

of a silver coin which bears the

Roman inscription “ Juba Rex.”

Still, an anonymous archaeologist,

(Steinbüchel,)32 suggests, that this ef-

figy, with its peculiar African headdress,

might represent an African Jupiter,

rather than a king, since his

features are somewhat ideal, and the

sceptre on the shoulder of the bust is

an attribute of Jupiter, or of Juno,

exceptionally only given to kings.

As your object in exhibiting the portrait

of Juba was principally to show,

Fig. 5.

to some illiterate Phil Ethiopians, that

the inhabitants of Northern Africa

were not negroes, the explanation of

Steinbüchel becomes a still stronger argument for your views. If

it can be maintained, then the published head is not the effigy of an

individual Mauritanian king, by descent and marriage closely allied

to several Greek dynasties (for instance, to the Ptolemies), but is the

representative type of the population of the northern shores of

Africa; and the slight modification of the Arab features, observed in

his face, becomes, therefore, a new argument for the affinity of Berber

and Shemitic races. The peculiar head-dress of the bust is mentioned

as African by Strabo,33 who says that the same costume prevailed

all along the northern coast of Africa up to Egypt, where it

borders on Libya. Silius Italicus describes it very characteristically

as a rigid bonnet formed by long hair overshadowing the forehead.34

We see it on the triumphal arch of the Emperor Constantine, as dis-

mguishmg the Numidian auxiliary horsemen;35 and it seems that it

extended even beyond the limits mentioned by Strabo, since it is

ound upon Egyptian reliefs representing Nubians as well as fulll

i l 1!6®1’068I for instance> compare “Types,” page 249, and figs.

166,167, 168, 169, 170, and 171. .

__VL Besides these effigies belonging to the domain of Greek art,

„ Of Mankind, p. 136, fig. 38:—Afrique Ancienne, Carthage.

!S ^ atal°9 einer Sammlung geschnittener Steine, Wien, 1834, p. 11 No. 144.

» ™AB0’ xvu' P- 528- " B e ilo r i, Arcus triumph.

Bunioorum, lib. 1, v. 404