disjointing a calf;138 but all this, is done before the tent of the king:

it is the royal stable and the royal kitchen which we see before us,—in

fact, “ eourhlife below stairs.” The rich Asiatic costume of the

Assyrians, wide and flowing, decorated with embroidery, fringes and

tassels, contrasts most strikingly with the prevalent nakedness of

Egyptian and Greek art. We are always reminded of the pomp, splendor

and etiquette of eastern courts. The proportions of the human

body are somewhat short and heavy, less animated in their action, but

more correctly modelled than in Egyptian reliefs. Nothing but an

occasional want of correctness about the shoulders and the eyes,

which, in the bas-reliefs, are drawn in the front-view, reminds us of the

infancy of art or of a traditionary hieratic style. The anatomical

knowledge, however, with which the muscles are sculptured, even

where the execution is rather coarse, surpasses the art of Egypt in

the time of the XVlith dynasty. The composition is generally

clear, the space conveniently and symmetrically filled with figures,

and the relief, to a certain degree, has ceased to be a mere architectural

decoration: on the palace of E ssarh a d dq n , it has even become

a real tableau. For all this, we cannot appreciate the merit of the

sculptures, if we pass our judgment upon them independently of the

place for which they were originally destined. Accordingly, the

peculiarly Assyrian exaggeration in representing the muscles of the

body has often been criticized;139 since it escaped the attention of our

modern art-critics, that this fault is only apparent, not real, being

produced exclusively by the different way in which the bas-reliefs

were lit in antiquity and modern times. In the hot climate and

under the glaring sun of Mesopotamia, the palaces were built principally

with the view to afford coolness and shade-; and therefore all

the royal halls were long, high and narrow, in order to exclude the

rays of the sun. They could, in consequence, but very imperfectly

have been lighted from above, through apertures in the colonnade

supporting the beams of the roof. A cool chiaroscuro reigned in all

the apartments; and unless the reliefs on the wall were intended

altogether to be lost to beholders, it was indispensable to have the

principal lines deeply cut into the alabaster, in order to produce a

sufficiently-intense shadow for making the composition and its details

apparent. The Assyrian sculptors, with true artistical feeling, calculated

upon the effect their works were to make in the king’s

palaces; but could not dream that their compositions were to be

138 B onomi, Nineveh and its Palacesy p. 2 2 8 -2 9 ; an octavo which admirably popularizes the

co stly fo lio s o f Botta and F landin’s Ninive.

188 Bonomi, Nineveh and its Palaces, p. 316.

exposed, 28 centuries later, to the close inspection of the critics of our

day in well-lighted museums.

When we claim a peculiar national type for Assyrian art, altogether

independent of Egyptian, we do not mean to deny accidental'

Egyptian influence, which, however, could not transform Assyrian

sculpture into a branch of Nilotic art. The beautiful embossed

bronze bowls, ivory bas-reliefs and statuettes found at Nineveh, are

certainly imitations of Egyptian models; but we encounter similar

artistical fashions at Rome in the time of Hadrian. They remained

altogether on the surface, and did not affect the national style. Still,

we do find some artistic “motives,” even on the best reliefs of Nim-

rood and Khorsabad, which show on the one hand, that the Assyrian

sculptors were acquainted with some Egyptian monuments of art;

and on the other, that this acquaintance ever continued to be superficial.

Thus, for instance, we often meet on Pharaonic battle-scenes,

with the vulture, holding a sword in its claws, soaring above the king,

as a symbol of victory. The Ninevite artists copied this representation,

but, unacquainted with its hieratic symbolical meaning, sculptured

the vulture simply as the hideous bird of prey, feeding upon the

corpses on the battle-field, and carrying the limbs into its eyrie. In

a similar way, the winged solar disc, the symbol of the heavenly sun,

was transformed in Assyria into the guardian-angel of the king himself,

and transferred at a later age to Persia as the Feruer.

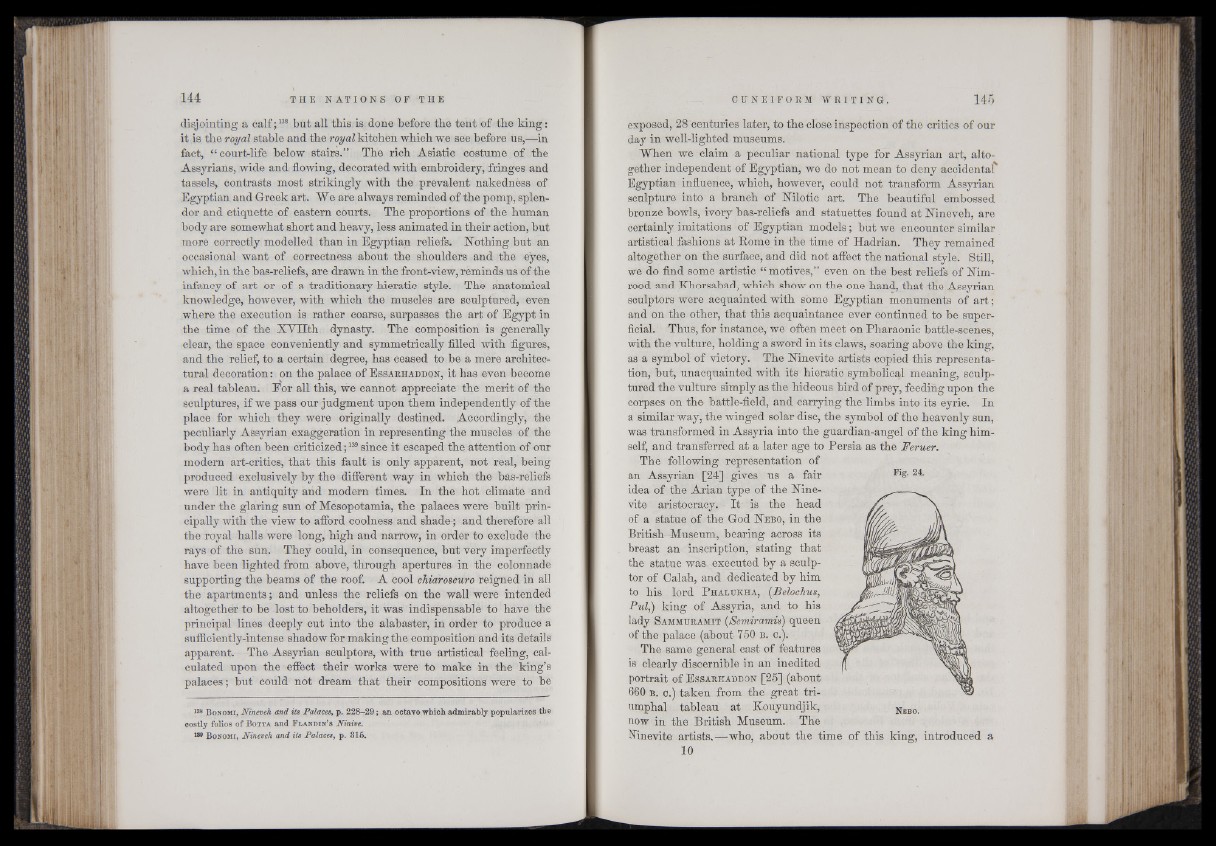

The following representation of

an Assyrian [24] gives us a fair

idea of the Arian type of the Ninevite

aristocracy. - It' is the head

of a statue of the God N ebo, in the

British Museum, bearing across its

breast an inscription, stating that

the statue was. executed by a sculptor

of Calah, and dedicated by him

to his lord P haltjkha, (Belochus,

Pul,) king of Assyria, and to his

lady S am m u r am it (Semiramis) queen

of the palace (about 7 5 0 b. c.).

The same general cast of features

is clearly discernible in an inedited

portrait of E s s a r e a d b o n [ 2 5 ] (about

66 0 b . c .) taken from the great triumphal

tableau at Kouyundjik,

now in the British Museum. The

Ninevite artists.—who, about the time of this king, introduced a

10

Fig. 24.

N ebo.