and their workmanship little artistical. Besides, we know from

Pliny that the family pride of the Romans cared more for the names

than for the likenesses of their ancestors. The admiral complains

that whilst the original wax-effigies represented the great men such

as they really had been (they were probably casts of the faces of the

deceased), a later age delighted in' silyer busts' and in the workmanship

of great masters (probably Greeks, and given to idealizing),

without regard to the likeness. Pliny’s complaint cannot apply to

the portrait of Scipio, which is entirely individual, and of that stern

and energetic cast which fully expresses the Roman character.

Scipio may be taken for a good specimen of the Roman patrician

type; for, at his time the aristocracy had not yet lost its national

purity by the admixture of foreign blood. Not less. characteristic

is the head of Agrippa [68],—the friend, minister and son-in-law of

Augustus, and maternal ancestor of the emperors Caligula, Claudius

and Nero. Next to the Roman type represented by these two highly

expressive portraits, let us consider the features of their enemies.

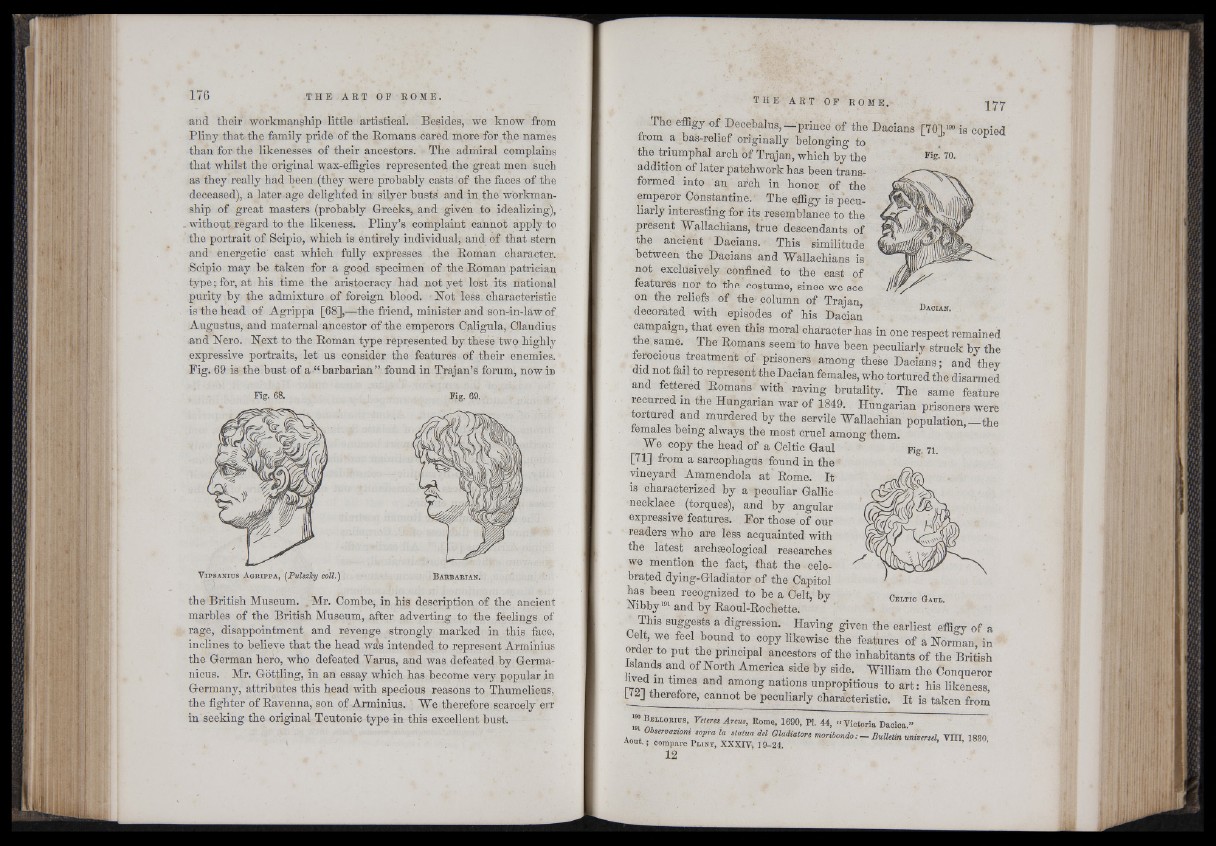

Pig. 69 is the bust of a “barbarian” found in Trajan’s forum, nowiD

Fig. 68. Fig. 69.

V ip sa n it js A g r i p p a , (Pulszky coll.) B a r b a r ia n .

the British Museum. , Mr. Combe, in his description of the ancient

marbles of the British Museum, after adverting to the feelings of

rage, disappointment and revenge strongly marked in this face,

inclines to believe that the head was intended to represent Arminius

the German hero, who defeated Varus, and was defeated by Germa-

nicus. Mr. Gottling, in an essay which has become very popular in

Germany, attributes this head with specious reasons to Thumelicus,

the fighter of Ravenna, son of Arminius. ; We therefore scarcely ear

in seeking the original Teutonic type in this excellent bust.

The effigy of Decebalus, —(prince of the Dacians [70],190 is copied

from a bas-relief originally belonging to

the triumphal arch of Trajan, which by the Fis' 70-

addition of later patchwork has been transformed

into an arch in honor of the

emperor Constantine.r The effigy is peculiarly

interesting for its resemblance to the

present Wallachians, true descendants of

the ancient Dacians. This similitude

between the Dacians and Wallachians is

not exclusively confined to the cast of

features nor to the costume, since we see

on the reliefs of the'column of Trajan,

decorated with episodes of his Dacian fjf"'

campaign, that even this moral character has in one respect remained

he same. The Romans seem to have been peculiarly struck by the

ferocious treatment of prisoners among these Dacians; and they

did not fail to represent the Dacian females, who tortured the disarmed

and fettered Romans with raving brutality.' The same feature

recurred in the Hungarian war of 1849. Hungarian prisoners were

tortured and murdered by the servile Wallachian population,-the

iemales being always the most cruel among them.

We copy the head of a Celtic Gaul

[71] from a sarcophagus found in the

vineyard Ammendola at Rome. It

is characterized by a peculiar Gallic

necklace (torques), and by angular

expressive features. Bor those of our

readers who are less acquainted with

the latest archaeological researches

we mention the fact, that the celebrated

dying-Gladiator of the Capitol

has been recognized to be a Celt, by

Nibby191 and by Raoul-Rochette.

This suggests a digression. Having given the earliest effigy of a

Celt, we feel bound to copy likewise the features of a Norman, in

order to put the principal ancestors of the inhabitants of the British

Islands and of North America side by side. William the Conqueror

2 ? tT 6S and am°ng nations »»Propitious to art: his likeness,

L J therefore, cannot be peculiarly characteristic. It is taken from

B e llob ic s, Vetera Arcus, Roma, 1690, PI. 44, “ Victoria Dacica.”

Observaziom soprala statu, del Gladiators moriboado.— Bulletin universel, VHI, 1830

Aout.; compare P u n y , XXXIV, 19-24

12

Fig. 71.

C e l t ic G a u l .