illustrates a remarkable head, which may serve as a type of the genuine

Egyptian conformation. The long oval cranium, the receding

forehead, gently aquiline nose, and retracted chin, together with the

marked distance between the nose and mouth, and the long, smooth

hair, are all characteristic of the monumental Egyptian,” and well

shown in Figs. 44, 45, 46 (retro). “ To this we may add, that the most

deficient part of the Egyptian skull is the coronal region, which is

extremely low, while the posterior chamber is remarkably full and

prominent.”

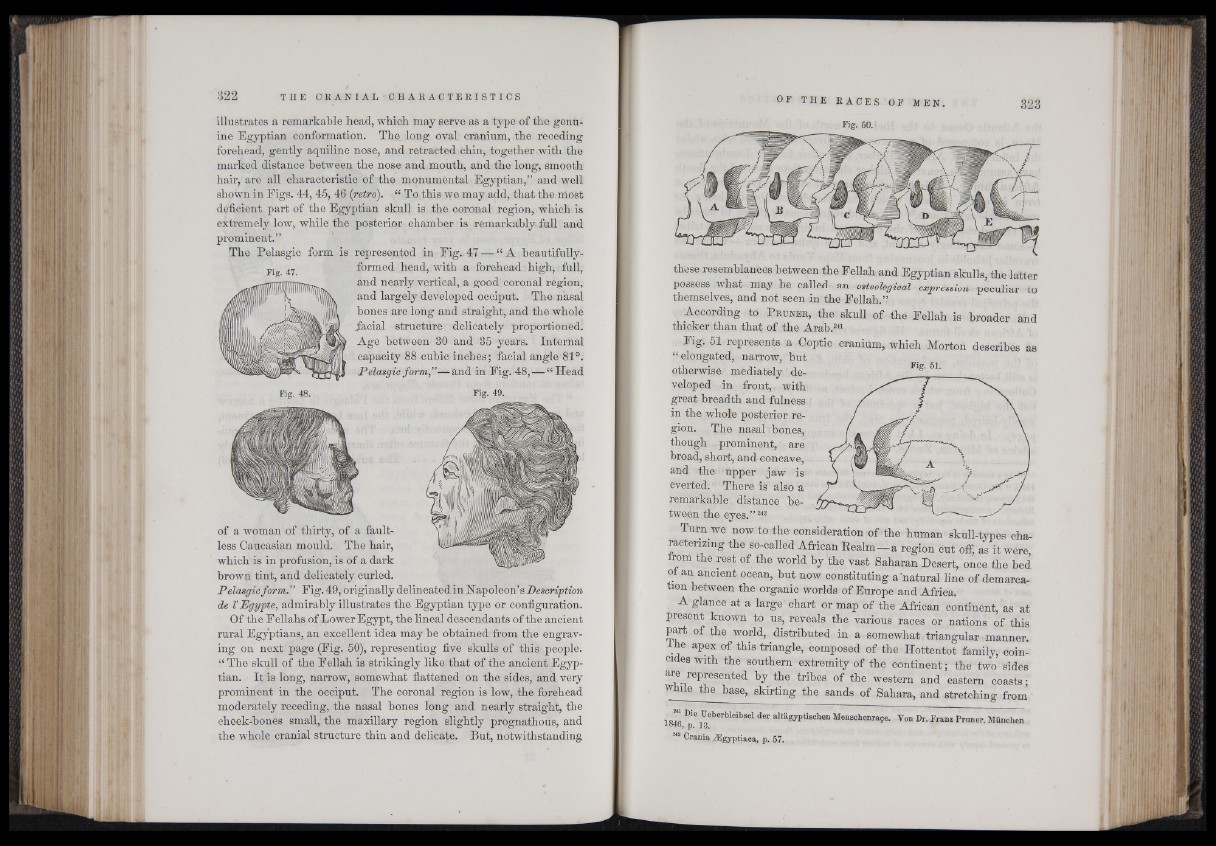

The Pelasgic form is represented in Fig..47 — “ A beautifully-

Fig 47 formed head, with a forehead high, full,

and nearly vertical, a good coronal region,

and largely developed occiput. The nasal

bones are long and straight, and the whole

.facial structure delicately proportioned.

Age between 30 and 35 years. Internal

capacity 88 cubic inches; facial angle 81°.

Pelasgic form,”-— and in Fig. 48, — “Head

Fig. 48. Fig. 49.

of a woman of thirty, of a faultless

Caucasian mould. The hair,

which is in profusion, is of a dark

brown tint, and delicately curled.

Pelasgicform.” Fig. 49, originally delineated in Napoleon’s Description

de TEgypte, admirably illustrates the Egyptian type or configuration.

Of the Fellahs of Lower Egypt, the lineal descendants of the ancient

rural Egyptians, an excellent idea may he obtained from the engraving

on next page (Fig. 50), representing five skulls of this people.

“ The skull of the Fellah is strikingly like that of the ancient Egyptian.

It is long, narrow, somewhat flattened on the sides, and very

prominent in the occiput. The coronal region is low, the forehead

moderately receding, the nasal bones long and nearly straight, the

cheek-bones small, the maxillary region slightly prognathous, and

the whole cranial structure thin and delicate. But, notwithstanding

these resemblances between the Fellah and Egyptian skulls, the latter

possess what may be called an osteological expression peculiar to

themselves, and not seen in the Fellah.” j

According to B r u n e r , the skull of the Fellah is broader a n d

thicker than that of the Arab.241

Fig; 51 represents a Coptic cranium, which Morton describes as

“ elongated, narrow, but

otherwise mediately de- Flg' 51'

veloped in front, with

great breadth and fulness

in the whole posterior region.

The nasal bones,

though prominent, are

broad, short, and concave,

and the upper jaw is

everted. There is also a

remarkable distance between

the eyes.”342

Turn we now to the consideration o f the human skull-types characterizing

the so-called African Bealm—a region cut off, as it were,

from the rest of the world by the vast Saharan Desert, once the bed

ot an ancient ocean, but now constituting a natural line of demarcation

between the organic worlds of Europe and Africa.

A glance at a large chart or map of the African continent, as at

present known to us, reveals the various races or nations of this

part of the world, distributed in a somewhat triangular manner,

t he apex of this triangle, composed of the Hottentot family, coincides

with the southern extremity of the continent; the two sides

are represented by’the tribes of the western and eastern coasts;

W 1 e base, skirting the sands of Sahara, and stretching from

i Dle „Ueberbleibsel der altagyptischen *o40, p# Menschenrape. Von Dr. Franz Prnner, München

m Crania .ffigyptiaca, p. 67.