A Penjur of Lhassa is thus described by H odgson :

“ Face moderately large, sub-ovoid, widest between angles of jaws, less between

cheek-bones, which are prominent, but not very. Forehead rather low, and narrowing somewhat

upwards; narrowed also transversely, and much less wide than ,the back of the nead.

Frontal sinus large, and brows heavy. Hair of eye-brows and lashes sufficient; former not

arched, but obliquely descendent towards the base of nose. Eyes of good size and shape,

but the inner angle decidedly dipt, or inclined downwards, though the outer is not curved

up. Iris a fine, deep, clear, chestnut-brown. Eyes wide apart, but well and distinctly

separated by the basal ridge of nose, not well opened, cavity being filled with flesh. Nose

sufficiently long, and well raised, even at base, straight, thick, and fleshy towards the end,

with large wide nares, nearly round. Zygomas large and salient, but moderately so. Angles

of the jaws prominent, more so than zygomas, and face widest below the ears. Mouth

moderate, well-formed, with well-made, closed lips, hiding the fine, regular, and no way

prominent teeth. Upper lip long. Chin rather small, round, well formed, not retiring.

Vertical line of the face very good, not at all bulging at the mouth, nor retiring below, and

not much above, but more so there towards the roots of the hair. Jaws large. Ears moderate,

well made, and not starting from the head. Head well formed and round, but longer

& parte post than cb parte ante, or in the frontal region; which is somewhat contracted crosswise,

and somewhat narrowed pyramidally upwards.................. Mongolian cast of features

decided, but not extremely so ; and expression intelligent and amiable.” 152

K xa po r th has shown that a general resemblance prevails between

the languages of the Turk, Mongolian, and Tungusian. The foregoing

remarks upon the cranial characters of these people, are, to

some extent, confirmatory of the slight affinity here supposed to he

indicated. The Turk and Mongol, however, appear to me to he

more related to each other than to the Tungusian, whose cranial

conformation must rather be Regarded as transitionary from the

pyramidal lype. Indeed, the Tungusian tribes seem to connect the

Chinese with the frozen North; for, in a modified degree, the same

differences which separate the true Hyperborean from the typical

Mongol, also separate the Chinese from the latter. In other words,

the Chinese nation, in the form of their heads, resembles the great

Inuit family more than the Mongolian. This opinion is based upon

the critical examination of eleven Chinese skulls, obtained from

various sources, and now comprised in the Mortonian collection.

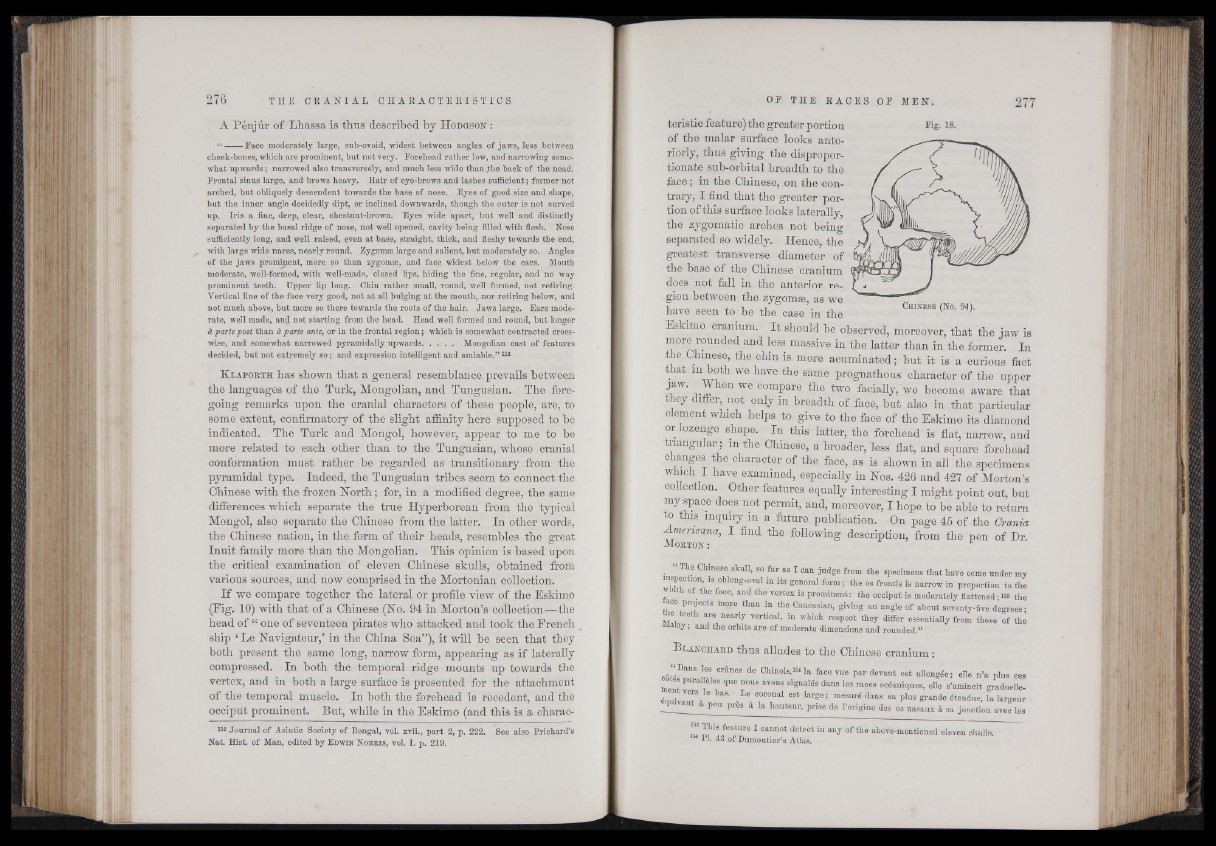

If we compare together the lateral or profile view of the Eskimo

(Pig. 10) with that of a Chinese (Ho. 94 in Morton’s collection—the

head of “ one of seventeen pirates who attacked and took the French

ship ‘Le Navigateur,’ in the China Sea”), it will he seen that they

both present the same long, narrow form, appearing as if laterally

compressed. In both the temporal ridge mounts up towards the

vertex, and in both a large surface is presented for the attachment

of the temporal muscle. In both the forehead is recedent, and the

occiput prominent. But, while in the Eskimo (and this is a charac-

162 Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. xvii., part 2, p. 222. See also Prichard’s

Nat. Hist, of Man, edited by E d w in N o r r i s , vol. I . p. 219.

teristie feature) the greater portion

of the malar surface looks anteriorly,

thus giving the disproportionate

sub-orbital breadth to the

face; in the Chinese, on the contrary,

I find that the greater portion

of this surface looks laterally,

the zygomatic arches not being

separated so widely. Hence, the

greatest transverse diameter of

the base of the Chinese cranium

does not fall in the anterior region

between the zygom®, as we

have seen to he the case in the

Fig. 18.

Chinese (N o. 91).

Es imo cranium. It should be observed, moreover, that the jaw is

more rounded and less massive in the latter than in the former. In

the Chinese, the chm is more acuminated; hut it is a curious fact

. ln,. ° We bave tJle same prognathous character of the upper

jaw. When we compare the two facially, we become aware that

they difier, not only in breadth of face, but also in that particular

element which helps to give to the face of the Eskimo its diamond

or lozenge shape. In this latte*, the forehead is flat, narrow, and

triangular^ in the Chinese, a broader, less flat, and square forehead

changes the character of the face, as is shown in all the spefeimens

which I have examined, especially in Nos. 426 and 427 of Morton’s

collection. Other features equally interesting I might point out, hut

my space does not permit, and, moreover, I hope to be able to return

to this inquiry in a future publication. On page 45 of the Crania

Amencana, I find the following description, from the pen of Dr.

Mouton :

“ The Chinese skull, so far as I can judge from the specimens that have come under my

■ g S i 1S oWong"OTal m lts several form ; the os frontis is narrow in proportion to the .

i ot the face, and the vertex is prominent: the occiput is moderately flattened; »» the

ace projeots more than in the Caucasian, giving an angle of about seventy-five degrees-

me teeth are nearly vertical, in which respect they differ essentially from those of the

a » an(* orbits are of moderate dimensions and rounded.”

B lanchard thus alludes to the Chinese cranium :

côtl D“ S i l °râneS de Chinois’15* Ia fece ™e par devant est allongée; elle n’a plus ces

m e n t ? n0US aT°nS slgnalés dans les races océaniques, elle s’amincit graduelleéouivJTa

LS °°r0nal 6St la 'g6! mesuré dans sa Plus grande étendue, la largeur

Jtmvaut a peu près à la hauteur, prise de l’origine des os nasaux à sa jonction avec les

“ » This feature I cannot detect in any of the above-mentioned eleven airalln.

154 PI. 43 of Dumoutier’s Atlas.