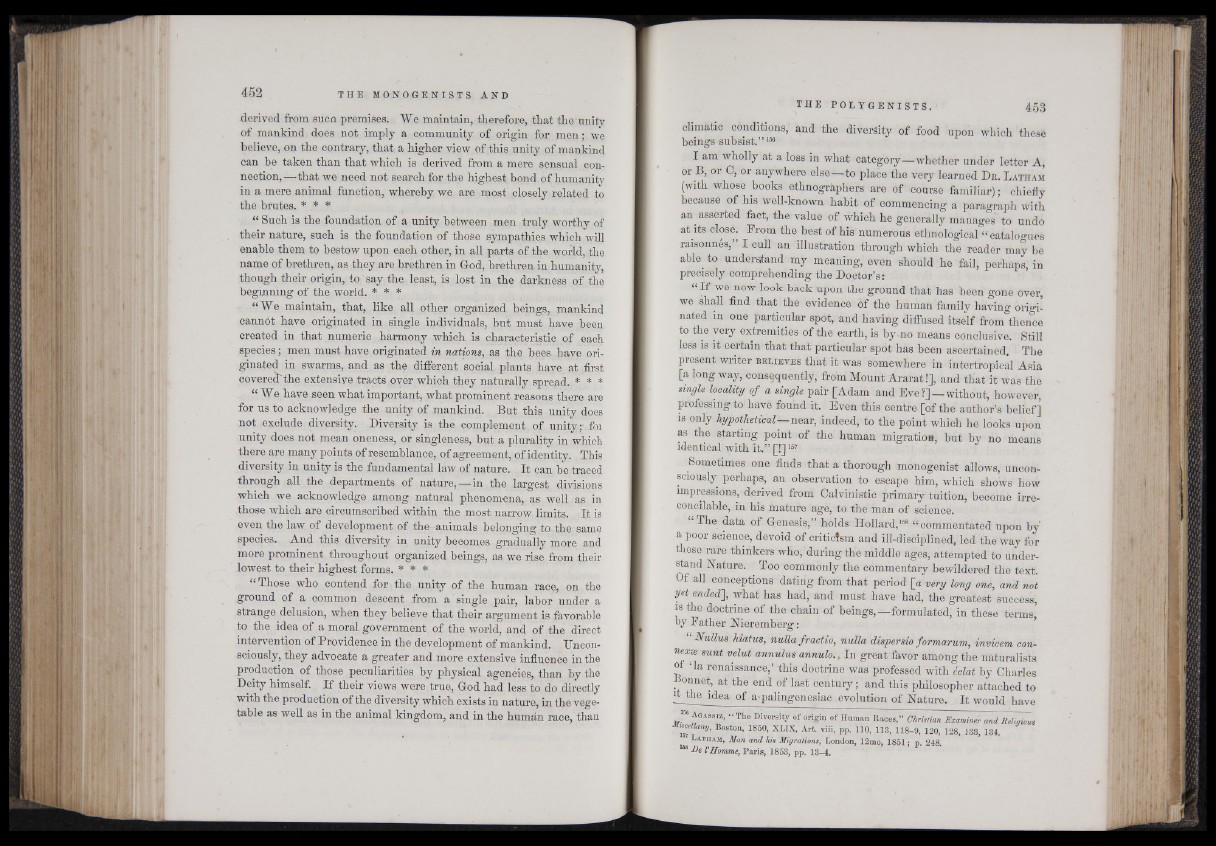

derived from sucn premises. We maintain, therefore, that the unitv

of mankind does not imply a community of origin for men; we

believe, on the contrary, that a higher view of this unity of mankind

can be taken than that which is derived from a mere sensual connection,—

that we need not search for the highest bond of humanity

in a mere animal function, whereby we are most closely related to

the brutes. * * *

“ Such is the foundation of a unity between men truly worthy of

their nature, such is the foundation of those sympathies which will

enable them to bestow upon each other, in all parts of the world, the

name of brethren, as they are brethren in God, brethren in humanity,

though their origin, to say the least, is lost in the darkness of the

beginning of the world. * * *

“We maintain, that, like all other organized beings, mankind

cannot have originated in single individuals, but must have been

created in that numeric harmony which is characteristic o f each

species; men must have originated in nations, as the bees have originated

in swarms, and as the different social plants have at first

coverea the extensive tracts oyer which they naturally spre,ad. * * *

“We have seen what important, what prominent reasons there are

for us to acknowledge the unity of mankind. But this unity does

not exclude diversity. Diversity is the complement of unity;- foi

unity does not mean oneness, or singleness, but a plurality in which

there are many points of resemblance, of agreement, of identity. This

diversity in unity is the fundamental law of nature. It can he. traced

through all the departments of nature,—in..the largest divisions

which we acknowledge among natural phenomena, as well as in

those which are circumscribed within the most narrow limits. It is

even the law of development of the animals belonging to the same

species. And this diversity in unity becomes gradually more and

more prominent throughout organized beings, as we rise from their

lowest to their highest forms. * * *

“ Those who contend for the unity of the human rac9, on the

ground of a common descent from a single pair, labor under a

strange delusion, when they believe that their argument is favorable

to the idea of a moral government of the world, and of the direct

intervention of Providence in the development of mankind. Unconsciously,

they advocate a greater and more extensive influence in the

production of those peculiarities by physical agencies, than by the

Deity himself. If their views were true, God had less to do directly

with the production of the diversity which exists in nature, in the vegetable

as well as in the animal kingdom, and in the human race, than

climatic conditions, and the diversity of food upon which these

beings subsist.” 156

I am wholly at a loss in what category—whether under letter A,

or B, or 0, or anywhere else—to place the very learned Da. L atham

(with whose books ethnogràphers are of' course familiar) ; chiefly

because of his well-known habit of commencing a paragraph with

an asserted fact, the value of which he generally manages to undo

at its close. From the best of his numerous ethnological “ catalogues

raisonnes, I cull an illustration through which the reader may he

able to understand my meaning, even should he fail, perhaps in

precisely comprehending the Doctor’s:

“ If we now look back upon the ground that has been gone over,

we shall find that the evidence ¿f the human family having originated

in one particular spot, and having diffused itself from thence

to the very extremities of the earth, is by-no means conclusive. Still

less is it certain that that particular spot has been ascertained. The

present writer b e l iev e s that it was somewhere in intertropical Asia

[a long way, consequently, front Mount Ararat !], and that it was the

single locality of a single pair [Adam and Eve ?] — without, however,

professing to have found it. Even this centre [of the author’s belief]

is only hypothetical-- near, indeed, to the point which he looks upon

as thé starting point of the human migration, but by no means

identical with, it.” [!]157

Sometimes one finds that a thorough monogenist allows, unconsciously

perhaps, an observation to escape him, which shows how

impressions, derived from Galviuistic primary tuition, become irreconcilable,

in his mature age, to the man of science.

The data of Genesis,” holds Hollard,168, “ commentated upon by

a poor science, devoid of criticism and ill-disciplined, led the way for

those rare thinkers who,r during the middle ages, attempted to understand

Nature, t Too commonly the commentary bewildered the text.

Of all conceptions dating from that period [a very long one, and not

yet ended], what has had, and must have had, the greatest success,

is the doctrine of the chain of beings,—formulated, in these terms,

by Father Nieremberg:

‘N’ullus hiatus, nulla fractio, nulla dispersio formarum., invicem con-

nexse sunt velut annulus annulo., In great favor among the naturalists

of ‘la renaissance,’ this doctrine was professed with éclat by Charles

Bonnet, at the end of last century; and this philosopher attached to

! ldea of a'palingenesiac evolution of Nature. It would have

156 Agassiz, “ The Dirersity of origin of Human Races,” Christian Examiner m i Religious

wcellany, Boston, 1850, XLIX, Art. viii, pp. 110, 113, 118-9, 120, 128, 133, 134.

Latham, Man and his Migrations, London, 12mo, 1851 ; p. 248.

188 De l’Homme, Paris, 1853, pp. 13-4.