that of the Indo-Chinese peninsula, and that of the Sunda Islands, Borneo, and the Philippines.

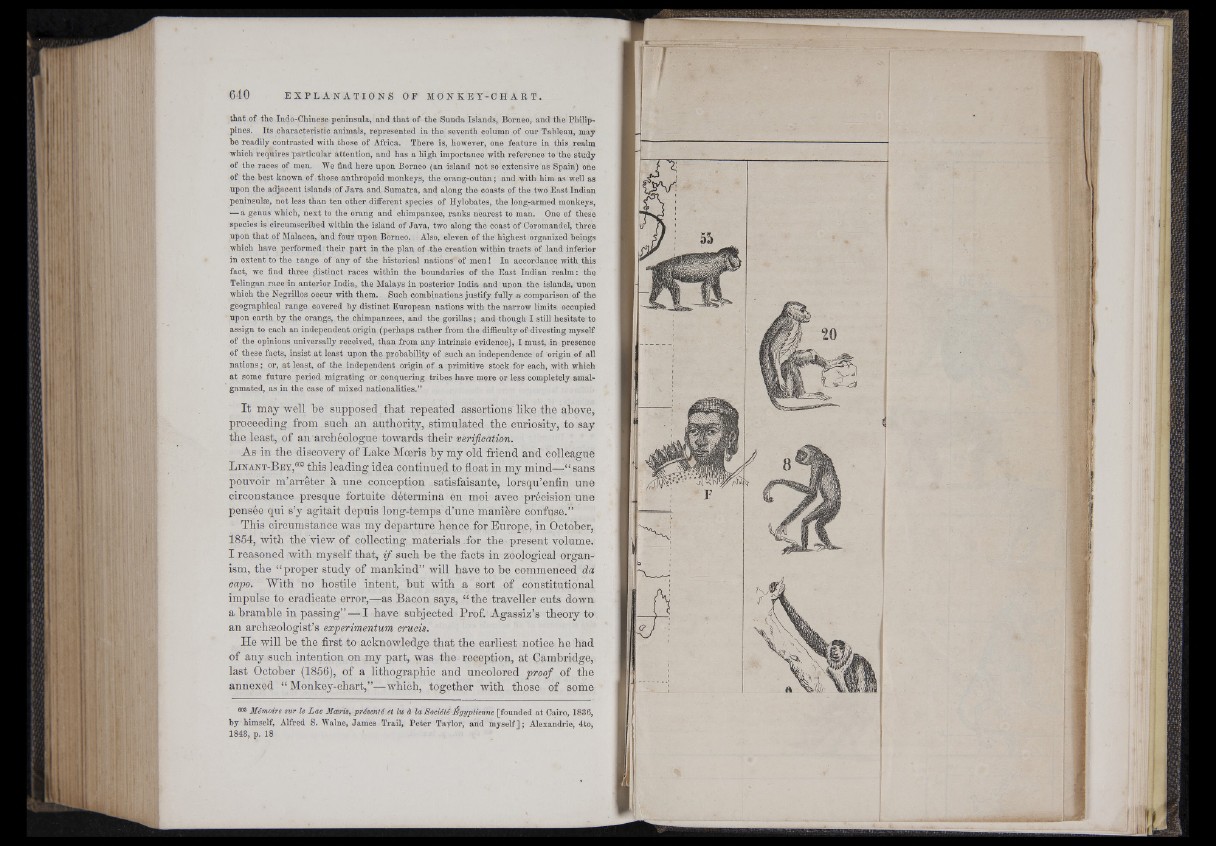

Its characteristic animals, represented in the seventh column of our Tableau, may

be readily contrasted with those of Africa. There is, however, one feature in this realm

which requires particular attention, and has a High importance with reference to the study

of the races of men. We find here upon Borneo (an island not so extensive as Spain) one

of the best known of those anthropoid monkeys, the orang-outan ; and with him as well as

upon the adjacent islands,of Java and Sumatra, and along the coasts of the two East Indian

peninsulæ, not less than ten other different species of Hylobates, the long-armed monkeys,

—a genus which, next to the orang and chimpanzee, ranks nearest to man. One of these

species is circumscribed within the island of Java, two along the coast of Coromandel, three

upon that of Malacca, and four upon Borneo. Also, eleven of the highest organized beings

which have, performed their part in the plan of -the creation within tracts òf land inferior

in extent to the range of any of the historical nations" of men ! In accordance with this

fact, we find three distinct races within the boundaries of the East Indian realm: the

Telingan race in anterior India, the Malays in posterior India and upon the islands, upon

which the Negrillos occur with them. Such combinations justify fully a comparison of the

geographical range covered by distinct European nations with the narrow limits occupied

upon earth by the orangs, the chimpanzees, and the gorillas; and though I still hesitate to

assign to each an independent origin (perhaps rather from the difficulty of divesting myself

of the opinions universally received, than from any intrinsic evidence), I must, in presence

of these facts, insist at least upon the probability of such an independence of origin of all

nations; or, at least, of the independent origin of a primitive stock for each, with which

at some future period migrating or conquering tribes have more or less completely amalgamated,

as in the case of mixed nationalities.”

It may well be supposed that repeated assertions like the above,

proceeding from such an authority, stimulated the curiosity, to say

the least, of an archéologue towards their verification.

As in the discovery of Lake Moeris by my old friend and colleague

L in a n t -B ey,™ this leading idea continued to float in my mind—“ sans

pouvoir m’arrêter à une conception satisfaisante, lorsqu’enfin une

circonstance presque fortuite détermina en moi avec précision une

pensée qui s’y agitait depuis long-temps d’une manière confuse.”

This circumstance was my departure hence for Europe, in October,

1854, with the view of collecting materials for the present volume.

I reasoned with; myself that, if such be the facts in zoological organism,

the “proper study of mankind” will have to be commenced da

capo. With no hostile intent, but with a sort of constitutional

impulse to eradicate error,—as Bacon says, “ the traveller cuts down

a bramble in passing” — I have subjected Prof. Agassiz’s theory to

an arehæologist’s experimentum crucis.

He will be the first to acknowledge that the earliest notice he had

of any such intention on my part, was the reception, at Qambridge,

last October (1856), of a lithographic and uncolored proof of the

annexed “ Monkey-chart,”—which, together with those of some

603 Mémoire sur le Lac Moeris, présenté et lu à la Société Égyptienne [founded at Cairo, 1836,

by himself, Alfred S. Walne, James Trail, Peter Taylor, and myself] ; Alexandrie, 4to,

1843, p. 18