-M tr /

Fig. ]

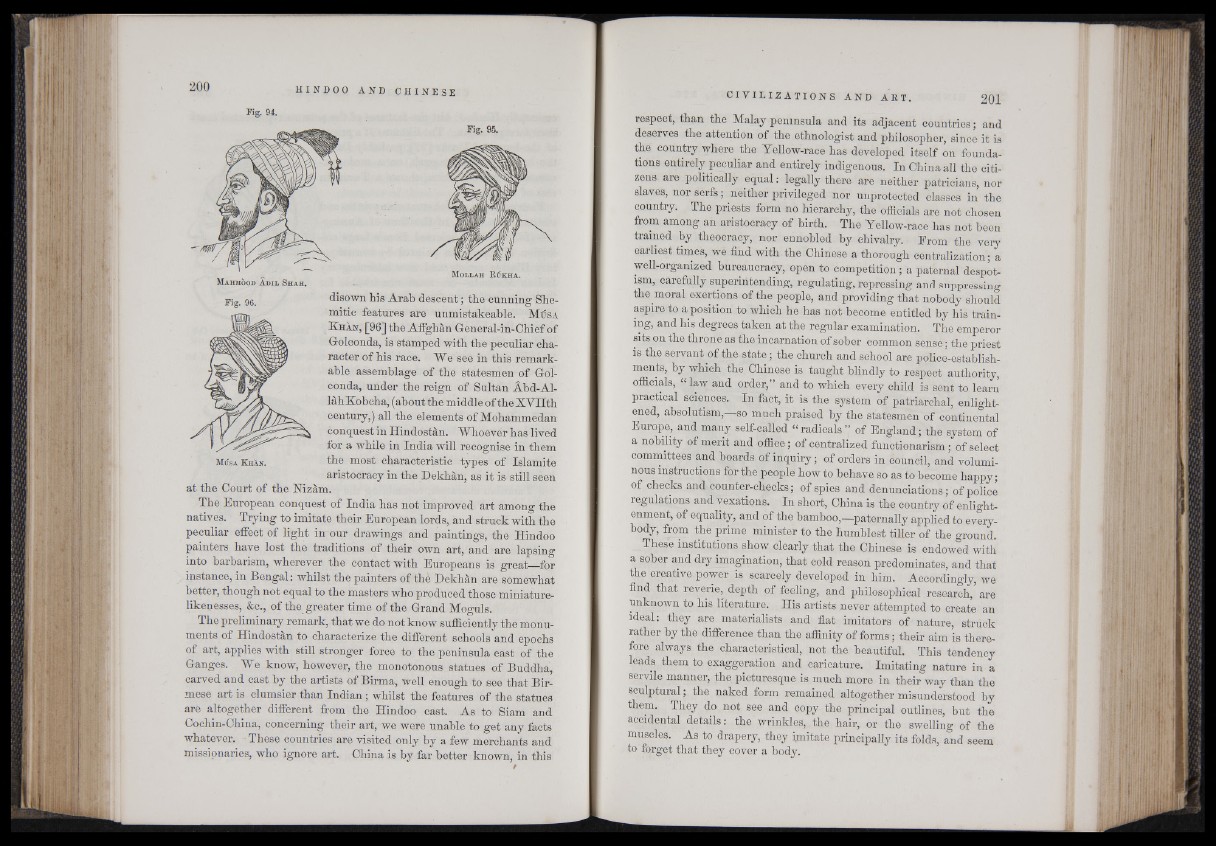

Ma iim o o d A d il S h a h .

Fig. 96.

M o l l a h R u k h a .

disown his Arab descent; the cunning She-

mitic features are unmistakeable. M ú sa

K h a n , [96] the Affghán General-in-Chief of

Golconda, is stamped with the peculiar character

of his race. We see in this remarkable

assemblage of the statesmen of Golconda,

under the reign of Sultan Ahd-Allah

Kobcha, (about the middle of theXVUth

century,) all the elements of Mohammedan

conquest in Hindostán. Whoever has lived

for a while in India will recognise in them

the most characteristic types of Islamite

aristocracy in the Dekhán, as it is still seen

at the Court of the Mzám.

The European conquest of India has not improved art among the

natives. Trying to imitate their European lords,, and struck with the

peculiar effect of light in our drawings- and paintings, the Hindoo

painters have lost the traditions of their own art, and are lapsing

into barbarism, wherever the contact with Europeans is great—for

instance, in Bengal: whilst the painters of the Dekhán are somewhat

better, though not equal to the masters who produced those miniature-

likeuesses, &c., of the greater time of the Grand Moguls.

The preliminary remark, that we do not know sufficiently the monuments

of Hindostán to characterize the different schools and epochs

of art, applies with still stronger force to the peninsula east of the

Ganges. We know, however, the monotonous statues of Buddha,

carved and cast by the artists of Birma, well enough to see that Bir-

mese art is clumsier than Indian; whilst the features of the statues

are altogether different from the Hindoo cast. As to Siam and

Cochin-China, concerning their art, we were unable to get any tacts

whatever. ■ These countries are visited only by a few merchants and

missionaries, who ignore art. China is by far better known, in this

respect, than the Malay peninsula and its adjacent countries ; and

deserves the attention of the ethnologist and philosopher, since it is

the country where the Yellow-race has developed itself on foundations

entirely peculiar and entirely indigenous. In China all the citizens

are politically equal: legally there are neither patricians, nor

slaves, nor sèrfs ; neither privileged nor unprotected classes in the

country. The priests form no hierarchy, the officials are not chosen

from among an aristocracy of birth. The Yellow-race has not been

trained by theocracy, nor ennobled by chivalry. From the very

earliest times, we find with the Chinese a thorough centralization; a

well-organized bureaucracy, open to competition ; a paternal despotism,

carefully superintending, regulating, repressing and suppressing

the moral exertions of the people, and providing that nobody should

aspire to a position to which he has not become entitled by his training,

and his degrees taken at the regular examination. The emperor

sits on the throne as the incarnation of sober common sense ; the priest

is the servant of the state ; the church and school are police-establishments,

by which the Chinese is taught blindly to respect authority,

officials, “ law and order,” and to which every child is sent to learn

practical sciences. In fact, it is the system of patriarchal, enlightened,

absolutism,—so much praised by the statesmen of continental

Europe, and many self-called “ radicals ” of England; the system of

a nobility of merit and office ; of centralized functionarism ; of select

committees and boards of inquiry; of orders in council, and voluminous

instructions for the people how to behave so as to become happy ;

of checks and counter-checks; of spies and denunciations; of police

regulations and vexations. In short, China is the country of enlightenment,

of equality, and of the bamboo,—paternally applied to everybody,

from the prime minister to the humblest tiller of the ground.

These institutions show clearly that the Chinese is endowed with

a sober and dry imagination, that cold reason predominates, and that

the creative power is scarcely developed in him. Accordingly, we

find that reverie, depth of feeling, and philosophical research, are

unknown to his literature. His artists never attempted to create an

ideal: they are materialists and flat imitators of nature, struck

rather by the difference than the affinity of forms ; their aim is therefore

always the characteristical, not the beautiful. This tendency

leads them to exaggeration and caricature. Imitating nature in a

servile manner, the picturesque is much more in their way than the

sculptural ; the naked form remained altogether misunderstood by

them. They do not see and copy the principal outlines, but the

accidental details: the wrinkles, the hair, or the swelling of the

muscles. As to drapery, they imitate principally its folds, and seem

to forget that they cover a body.