■began to effect settlements and build bouses on tbe scenes where they had ravaged the villages

of the older British natives. The fufst cl'ass, we may infer, attempted little cultivation

of the s o i l ...............

“ Viewing Archaeology as one of the most essential means for the elucidatidn of primitive

history, it has been employed here chiefly in an attempt to trace out the-annals of our

country prior to that comparatively recent medieval.pdried at which the boldest of bur historians

have heretofore ventured to begin. ' The researches of the ethnologist Carry us back

somewhat beyond that epoch, and confirm many of those conclusions, especially in relation

to the dose affinity between the native arts and Celtic raises of Scotland and Ireland, at

which we have arrived by means of archaeological evidence. . . . But .we have found from

many independent sources of evidence, that the primeval history of Britain must be sought

for in the annals of older races than the Celtse, and in the remains of a people*of whom we

have as yet no reason to, believ.e that any philological traces are discoverable, though they

probably do exist mingled with later dialects, and especially in the topographical nomenclature,

adopted and modified, but in all likelihood not entirely superseded by later colonists.

With the earliest intelligible indices'of that primeval colonization of the British Isles our

archaeological records begin, mingling their'dim historic annals with the Iast^giant traces

of elder worlds; and, as an essentially independent element of historical research, they

terminate at the point where the isolation of Scotland ceases by its being embraced into

the unity of medieval Christendom.” 188

Mr. B ateman, who has carefully examined the ancient barrows

of North «Derbyshire, describes the skulls found in the oldest of

these known as the • Chambered Barrows -A? as being elongated

and boat-shaped (kumbe-kephalie form of Wilson). The crania

of the succeeding two varieties of harrows are of the brachy-

cephalie type, round and short, with prominent parietalia. In the

barrows of the “ iron age”—the 'most recent—he found the prevailing

form to approximate the oval heads of the modern inhabitants

of Derbyshire.1?9

From the foregoing statements, a remarkable fact becomes evident.

While B e tz ius, N ils so n, E schriciit, and W il d e are remarkably harmonious

in ascribing the brachy-cephalic type to the earliest or Stone

Period in Scandinavia, Denmark, and Ireland, we find W il so n and

B ateman equally accordant in considering the kumbe-kephalse as the

first men who trod the virgin soil of Caledonia and England. In the

present state of antiquarian research, then, we are forced to conclude

that the primitive inhabitants of Britain are identical with those of

Sweden and Denmark, but that in different parts of these countries

the order of their sequence has varied.

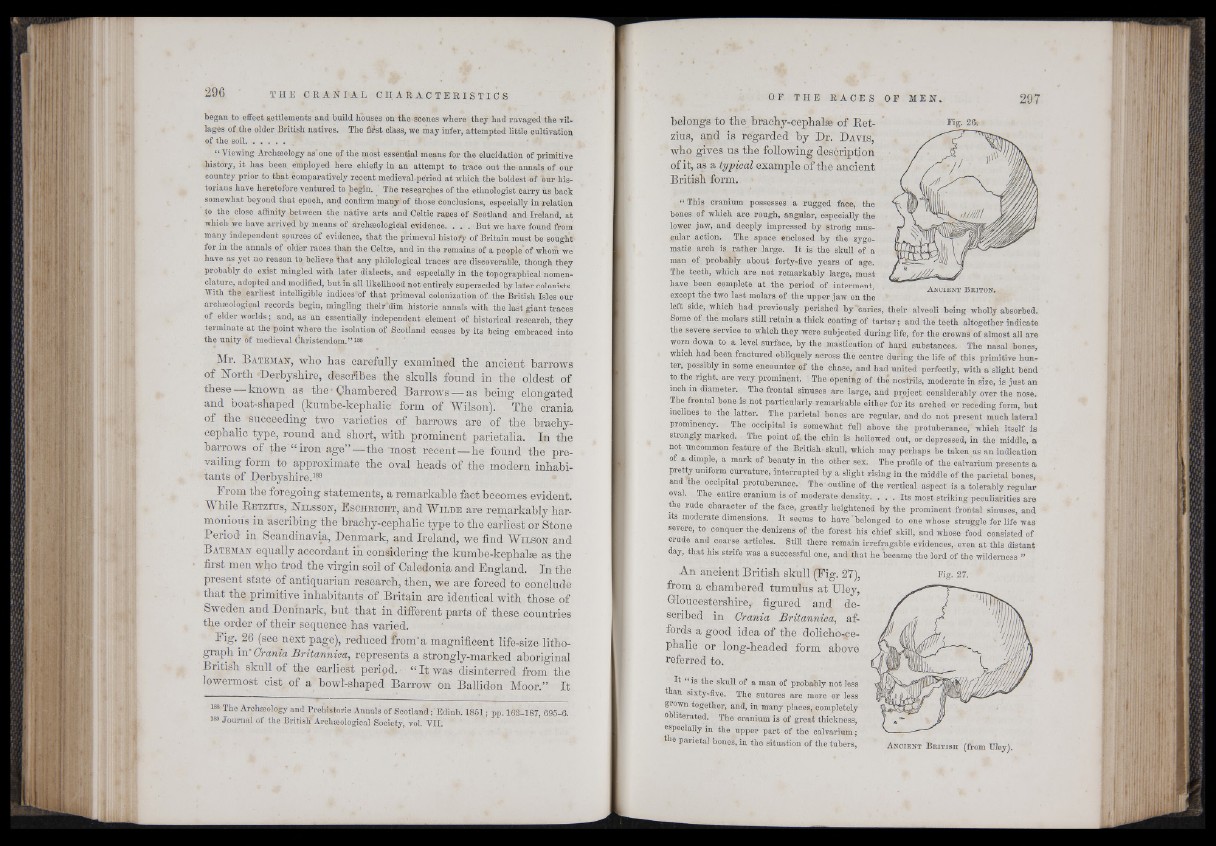

Fig. 26 (see next page), reduced irom'a magnificent life-size lithograph

in’ Crania Britannica, represents a strohgly-marked aboriginal

British skull of the earliest peripd. ■ “ It was disinterred from the

lowermost cist of a bowl-shaped Barrow on Ballidon Moor.” It

“ »■The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland ;'Edinb. 1851; pp. 163-187, 695-6.

189 Journal of tbe British Archaeological Society, vol. VII. ’

O B J u i i g e L U L i l t ; urauny-cepuaiæ 01 Itet- Fig. 26*

A n c ie n t B r i t o n .

zius, and is regarded by Dr. Davis,

who gives us the following description

of it, as a typical example of the ancient

British form.

“ This cranium possesses a rugged face, the

bones of which are rough, angular, especially the

lower jaw, and deeply impressed by stroüg muscular

action. The space enclosed by the zygomatic

arch is , rather large. It is the skull of a

man of, probably about forty-five years of age.

The teeth, which are not remarkably large, must

have been complete at the period of interment,

except the two last molars of the upper jaw on the

left side, which had previously perished by'caries, their alveoli being wholly absorbed.

Some of the molars still retain a thick coating of tartar ; and the teeth altogether indicate

the severe service to which they were subjected during life, for the crowns of almost all are

worn down to a level surface, by the maïstication of hard substances. The nasal bones,

which had been fractured obliquely across the centre during the life of this primitive hunter,

possibly in some encounter of the chase, and had united perfectly, with a slight bend

to the right, are very prominent. The opening of the nostrils, moderate in size, is just an

inch in diameter. ^ Thé frontal sinuses are large, and project, considerably over the nose.

The frontal bone is not particularly remarkable either for its arched or receding form, but

inclines to the latter. The parietal bones are regular, and do not present much lateral

prominency. The occipital is somewhat full above the protuberance, which itself is

strongly marked. The point ofrthe chin is hollowed out, or depressed, in the middle, a

not uncommon feature of the British-skull, which may perhaps be taken as an indication

of a dimple, a mark of beauty in the other sex. The profile of the calvarium presents a

pretty uniform curvature, interrupted by a slight rising in the middle of the parietal bones,

and the occipital protuberance.' The' outline of the vertical aspect is a tolerably regular

oval. The entire cranium is of moderate density. . . . Its most striking peculiarities are

tiie rude character of the face, greatly heightened by the prominent frontal sinuses, and

its moderate dimensions. It seems to have * belonged to one whose struggle for life was

severe, to conquer the denizens of the forest his chief skill, and whose food consisted of

crude and coarse articles. Still there remain irrefragable evidences, even at this distant

day, that gpj strife was a successful one, and that he became the lord of the wilderness ”

An ancient British skull (Fig. 27),

from a chambered tumulus at Uley,

Gloucestershire, figured and described

in Crania Britannica, affords

a good idea of the dolichocephalic

or long-headed form above

referred to.

It “ is the skull of a man of probably not less

than sixty-five. The sutures are more or less

grown together, and, in many places, completely

obliterated. The cranium is of great thickness,

especially in the upper part of the calvarium;

P ^ e ta l bones, in the situation of the tubers,

Fig. 27.

A n c ie n t B r i t i s h (from Uley).