having ever, before Visconti, been imagined to represent Lycurgus ;

and that in no case could it he taken for anything else than a fancy-

portrait, not more to he trusted than the statue of Coltjmbus,

commonly called the “ ninepin-player,” before your Capitol, or the

relief portrait of Daniel Boone in the Rotunda at Washington.

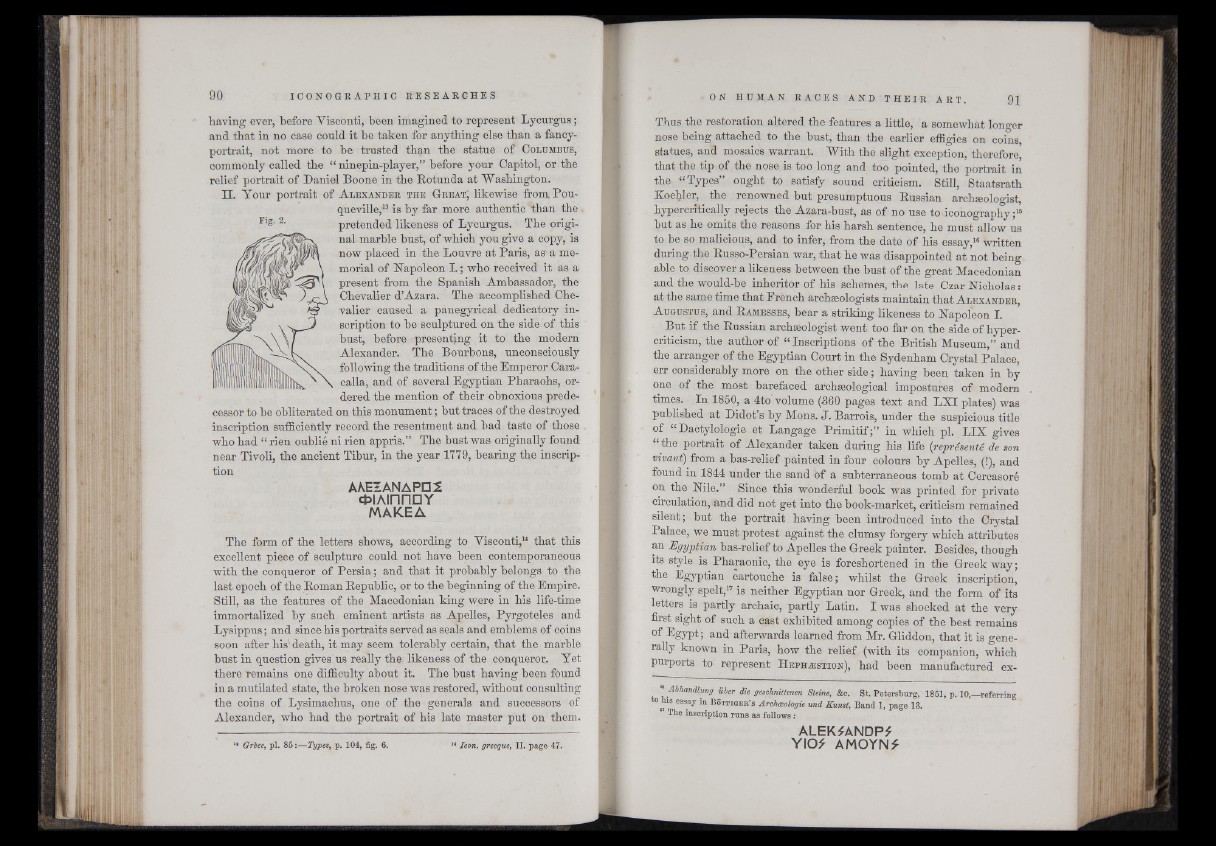

TT- Tour portrait of A l ex a n d e r t h e G reat; likewise from. Pou-

que ville,13 is by far more authentic than the

Flg' pretended likeness of Lycurgus. The original

marble bust, of which you give a copy, is

now placed in the Louvre at Paris, as' a memorial

of Napoleon I. ; who received it as a

present from the Spanish Ambassador, the

Chevalier d’Azara. The accomplished Chevalier

caused a panegyrical dedicatory inscription

to he sculptured on the side of this

bust, before presenting it to the modern

Alexander. The Bourbons, unconsciously

following the traditions of the Emperor Cara-

calla, and of several Egyptian Pharaohs, ordered

the mention of their obnoxious predecessor

to he obliterated on this monument ; but traces of the destroyed

inscription sufficieiitly record the resentment and bad taste of those

who had “ rien oublié ni rien appris.” The bust was originally found

near Tivoli, the ancient Tibur, in the year 1779, hearing the inscription

AAEIANAPD 2

c&iAinnnY

MAKEA

The form of the letters shows, according to Visconti,14 that this

excellent piece of sculpture could not have been contemporaneous

with the conqueror of Persia ; and that it probably belongs to the

last epoch of the Roman Republic, or to the beginning of the Empire.

Still, as the features of the Macedonian king were in his life-time

immortalized by such eminent artists as Apelles, Pyrgoteles and

Lysippus ; and since his portraits served as seals and emblems of coins

soon after his' death, it may seem tolerably certain, that the marble

bust in question gives us really the likeness of the conqueror. Yet

there remains one difficulty about it. The bust having been found

in a mutilated state, the broken nose was restored, without consulting

the coins of Lysimachus, one of the generals and successors of

Alexander, who had the portrait of his late master put on them.

18 Grèce, pi. 85 :—Types, p. 104, fig. 6. 14 Icon, grecque, II. page 47.

Thus the restoration altered the features a little, a somewhat longer

nose being attached to the bust, than the earlier effigies on coins

statues, and mosaics warrant. With the slight exception, therefore,

that the tip of the nose is too long and too pointed, the portrait in

the “Types” ought to satisfy sound criticism. Still, Staatsrath

Koehler, the renowned hut presumptuous Russian archæologist,

hypercrftically rejects the Azara-hust, as of no use to iconography;15

but as he omits the reasons for his harsh sentence, he must allow us

to be so malicious, and to infer, from the date of his essay,16 written

during the Russo-Persian war, that he was disappointed at not being

able to discover a likeness between the bust of the great Macedonian

and the would-be inheritor of his schemes, the late Czar Nicholas :

at the same time that Erench archaeologists maintain that A l exander,

A ugustus, and R amesses, hear a striking likeness to Napoleon I.

But if the Russian archæologist went too far on the side of hypercriticism,

the author of “ Inscriptions of the British Museum,” and

the arranger of the Egyptian Court in the Sydenham Crystal Palace,

err considerably more on the other side ; having been taken in by

one of the most barefaced archaeological impostures of modem

times. In 1850, a 4to volume (360 pages text and LXT plates) was

published at Didot s by Mons. J . Barrois, under the suspicious title

of “Dactylologie et Langage Primitif;” in which pi. LIX gives

“ the portrait of Alexander taken during his life {représenté de son

vivant) from a bas-relief painted in four colours by Apelles, (!), and

found in 1844 under the sand of a subterraneous tomb at Cereasoré

on the Nile.” Since this wonderful book was printed for private

circulation, and did not get into the book-market, criticism remained

silent; but the portrait having been introduced into the Crystal

Palace, we must protest against the clumsy forgery which attributes

an Egyptian bas-relief to Apelles the Greek painter. Besides, though

its style is Pharaonic, the eye is foreshortened in the Greek way;

the Egyptian cartouche is false; whilst the Greek inscription,

wrongly spelt,17 is neither Egyptian nor Greek, and the form of its

letters is partly archaic, partly Latin. 1 was shocked at the very

first sight of such a east exhibited among copies of the best remains

°f Egypt; and afterwards learned from Mr. Gliddon, that it is generally

known in Paris, how the relief (with its companion, which

purports to represent H e phæ st io n ), had been manufactured ex-

" Abhandlung über die geschnittenen Steine, &o. St. Petersburg, 1851, p. 10,—referring

to bis essay in B ö t t iq e e ’s Archäologie und Kunst. Band 1, page 13.

The inscription runs as follows :

ALEKMNDP*

YIO* AMOYN*