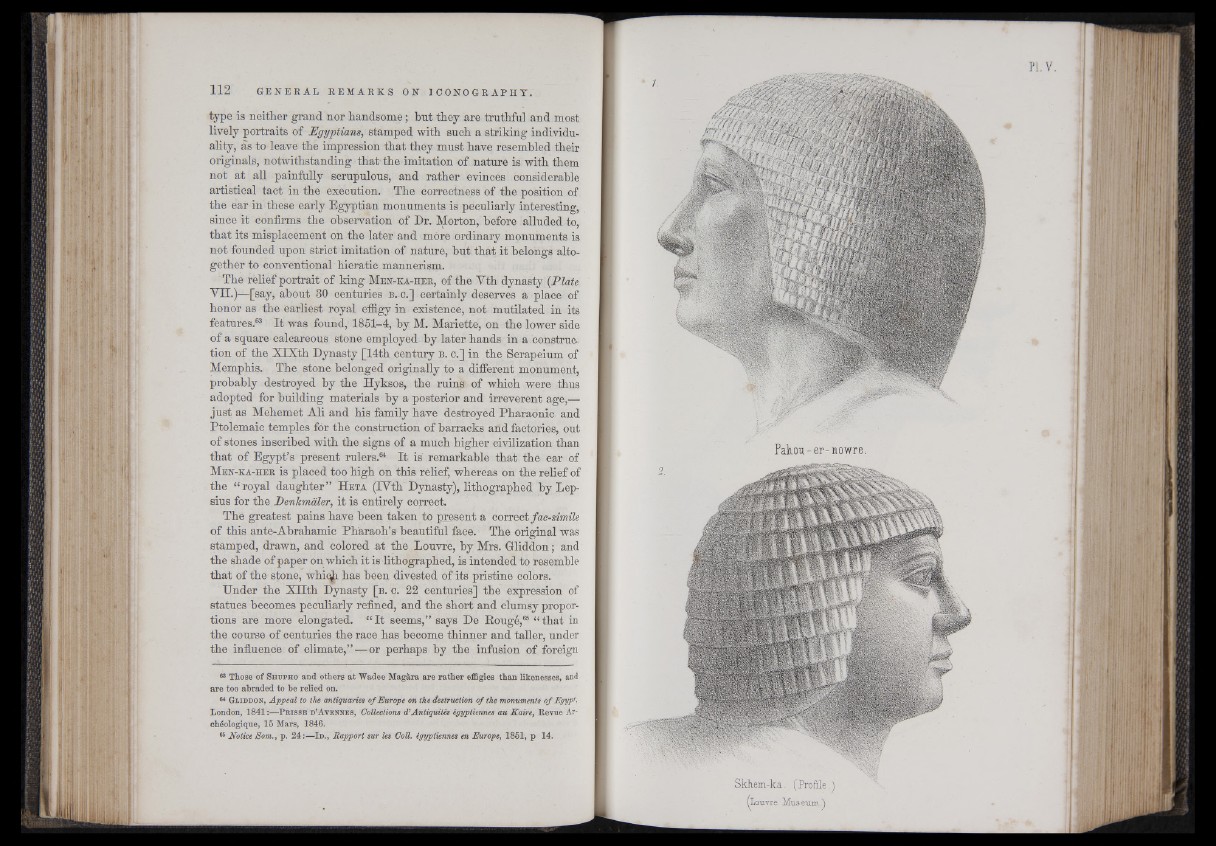

type is neither grand nor handsome ; bnt they are truthful and most

lively portraits of Egyptians, stamped with such a striking individuality,

às to leave the impression that they must have resembled their

originals, notwithstanding that the imitation of nature is with them

not at all painfully scrupulous, and rather evinces considerable

artistical tact in the execution. The correctness of the position of

the ear in these early Egyptian monuments is peculiarly interesting,

since it confirms the observation of Dr. Morton, before alluded to,

that its misplacement on the later and more ordinary monuments is

not founded upon strict imitation of nature, but.that it belongs altogether

to conventional hieratic mannerism.

The relief portrait of king M e n -e a -h e r , of the Yth dynasty {Plate

VII.)—[say, about 30 centuries b. c.] certainly deserves a place of

honoras the earliest royal effigy in existence, not mutilated in its

features.63 It was found, 1851-4, by M. Mariette, on the lower side

of a square calcareous stone employed by later hands in a construe-

tion of the XTXth Dynasty [14th century b. c.] in the Serapeium of

Memphis. The stone belonged originally to a different monument,

probably destroyed by the Hyksos, the ruins of which were thus

adopted for building materials by a posterior and irreverent age,—

just as Mehemet Ali and his family have destroyed Pharaonic and

Ptolemaic temples for the construction of barracks and factories, out

of stones inscribed with the signs of a much higher civilization than

that of Egypt’s present rulers.64 It is remarkable that the ear of

M en -ka-h e r is placed too high on this relief, whereas on the relief of

the “ royal daughter” H eta (TVth Dynasty), lithographed by Lep-

sius for the Denkmäler, it is entirely correct.

The greatest pains have been taken to present a correct facsimile

of this ante-Abrahamie Pharaoh’s beautiful face. The original was

stamped, drawn, and colored at the Louvre, by Mrs. Gliddon ; and

the shade of paper on which it is lithographed, is intended to resemble

that of the stone, whiqjh has been divested of its pristine colors.

Under the XHth Dynasty [ b . c. 22 centuries] the expression of

statues becomes peculiarly refined, and the short and clumsy proportions

are more elongated. “ It seems,” says De Rougé,65 “ that in

the course of centuries the race has become thinner and taller, under

the influence of climate,”—or perhaps by the infusion of foreign

63 T h o s e o f S h u p h o a n d o t h e r s a t W a d e e M a g à r a a r e r a t h e r e ffig ie s t h a n lik e n e s s e s , and

a r e to o a b r a d e d t o b e r e l i e d o n .

64 Gl id d o n , Appeal to the antiquaries of Europe on the destruction of the monuments of Egypt,

London, 1841 :—P r is s e d ’Av e n n e s , Collections (VAntiquités égyptiennes au Kairef R e r u e Archéologique,

15 Mars, 1846.

65 Notice Som., p . 24 :—I d . , Rapport sur les Coll. égyptiennes en Europe, 1851, p 14.

Pahou-er-nowre.

Skhem-ka. (Profile.)

(Louvre Muséum.)