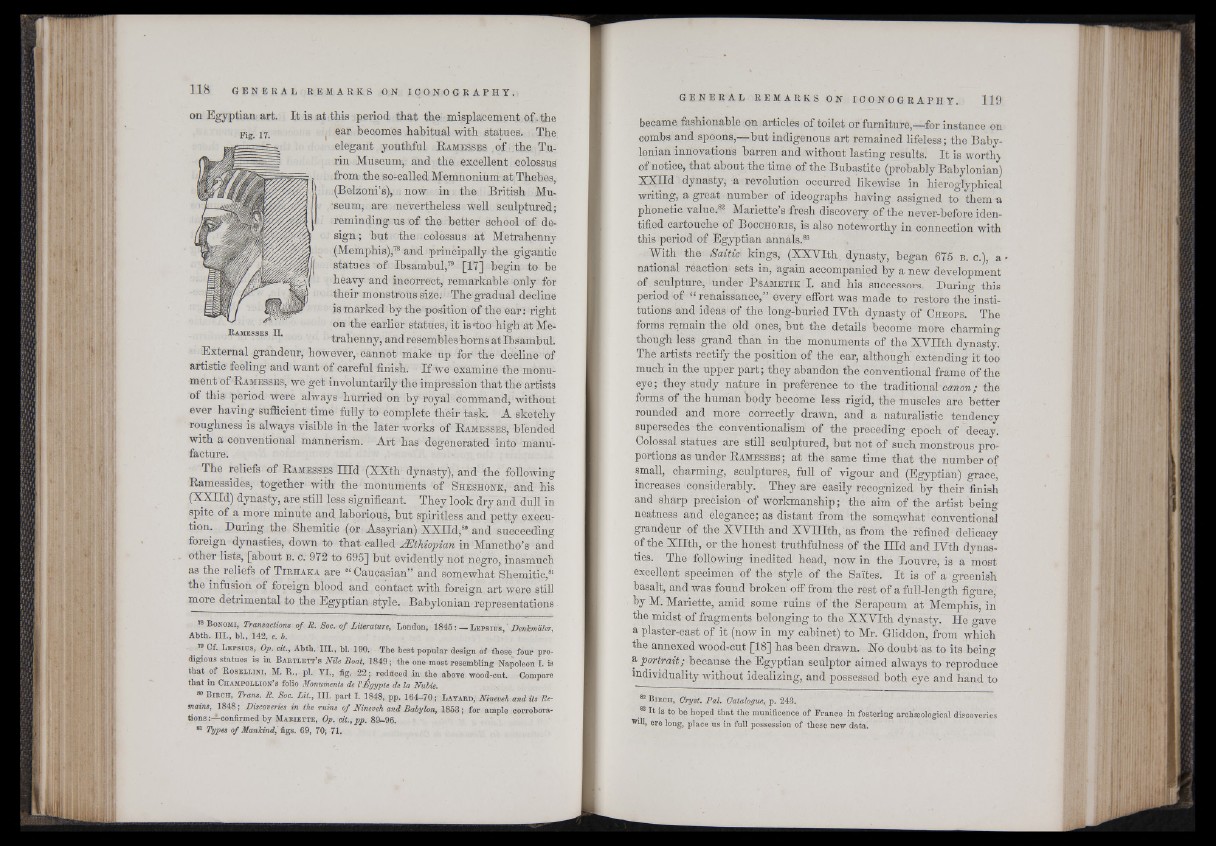

on Egyptian art. It is at this period that the misplacement of. the

ear becomes habitual with statues. The

elegant youthful R ames ses of the Turin

Museum, and the excellent colossus

from the so-called Memnonium at Thebes,

(Belzoni’s), now in the British Museum,

are nevertheless well sculptured;

reminding us of the better school of design;

but the colossus at Metrahenny

(Memphis);78 and principally the gigantic

statues of Ibsambul,79 [17] begin to he

heavy and incorrect, remarkable only for

their monstrous size; The gradual decline

is marked by the position of the ear: right

on the earlier statues, it is »too high at Metrahenny,

and resembles horns at Ibsambul.

Fig. 17.

R a m e s s e s II.

External grandeur, however, cannot make up for the decline of

artistic feeling and want of careful finish. If we examine the monument

of R am es se s, we get involuntarily the impression that the artists

of this period were always hurried on by royal command, without

ever having suflicient time fully to complete their task. A sketchy

roughness is always visible in the later works of R am es se s , blended

with a conventional mannerism. Art has degenerated into manufacture.

The reliefs of R ames se s Hid (XXth dynasty), and the following

Ramessides, together with the monuments of S h e sh o nk , and his

(XXHd) dynasty, are still less significant. They look dry and dull in

spite of a more minute and laborious, but spiritless and petty execution.

During the Shemitic (or Assyrian) XXÜd,8* and succeeding

foreign dynasties, down to that called 2.’Ethiopian in Manetho’s and

other lists, [about b . c. 972 to 695] but evidently not negro, inasmuch

as the reliefs of T ir h a k a are i£ Caucasian” and somewhat Shemitic,81

the infusion of foreign blood and contact with foreign art were still

more detrimental to the Egyptian style. Babylonian representations

re B o n om i, Transactions o f R. Soc. of Literature, London, 1845: — L e p s iu s , ' Denkmäler,

Abth. III., bl., 142, e. b.

w Cf. L e p s iu s , Op. cit., Abth. III., bl. 190. The best popular design of these four pro-

digious statues is in B a b t l e t t ’s Nile Boat, 1849; the one most resembling Napoleon I. is

that of R o s e i l ih i , M. R., pi. VI., fig. 22j redtloed in the above wood-cut. Compare

that in Ch am p o l l io n ’s folio Monuments de V.Egyple de la Nubie.

80 Bi e c h , Trans. R. Soc. Lit., III. part I. 1848, pp. 164—70; L a y a ed , Nineveh and its Remains,

1848; Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, 1853; for ample corroborations

confirmed by M a e ie t t e , Op. cit., pp. 89-96.

81 Types of Mankind, figs. 69, 70; 71.

became fashionable on articles of toilet or furniture,—for instance on

combs and spoons,— but indigenous art remained lifeless; the Babylonian

innovations barren and without lasting results. It is worth}

of notice, that about the time of the Bubastite (probably Babylonian)

XXHd dynasty; a revolution occurred likewise in hieroglyphical

writing, a great number of ideographs having assigned to them a

phonetic valued Mariette’s fresh discovery of the never-before identified

cartouche of B occhoris, is also noteworthy in connection with

this period of Egyptian annals.83

With the Saitiv kings, (XXVIth. dynasty, began 675 B. c.), a *

national reaction sets in, again accompanied by a new development

of sculpture, under B sam e tik I. and his successors. During this

period of “ renaissance,” every effort was made to restore the institutions

and ideas of the long-buried IVth dynasty of Cheops. The

forms remain the old ones, hut tne details become more charming

though less grand than in the monuments of the XVTIth dynasty.

The artists rectify the position of the ear, although' extending it too

much in the upper part; they abandon the conventional frame of the

eye; they study nature in preference to the traditional canon; the

forms of the human body become less rigid, the muscles are better

rounded and more correctly drawn, and a naturalistic tendency

supersedes the conventionalism of the preceding epoch of decay.

Colossal statues are still sculptured, but not of such monstrous proportions

as under R ames ses ; at the same time that the number of

small, charming, sculptures, full of vigour and (Egyptian) grace,

increases considerably. They are easily recognized by their finish

and sharp precision of workmanship; the aim of the artist being

neatness and elegance; as distant from the somewhat conventional

grandeur of the XVTIth and XV Tilth, as from the refined delicacy

of the Xllth, or the honest truthfulness of the Hid and IVth dynasties.

The following inedited head, now in the Louvre, is a most

excellent specimen of the style of the Sa'ites. It is of a greenish

basalt, and was found broken off from the rest of a full-length figure,

by M. Mariette, amid some ruins of the Serapeum at Memphis, in

the midst of fragments belonging to the XXVIth dynasty. He gave

a plaster-cast of it (now in my cabinet) to Mr. Gliddon, from which

the annexed wood-cut [18] has been drawn. Ho doubt as to its being

a portrait; because the Egyptian sculptor aimed always to reproduce

individuality without idealizing, and possessed both eye and hand to

82 Birch, Cryst. Pal. Catalogue, p. 243.

It is to be hoped that the munificence of France in fostering archæological discoveries

ere long, place us in full possession of these new data.