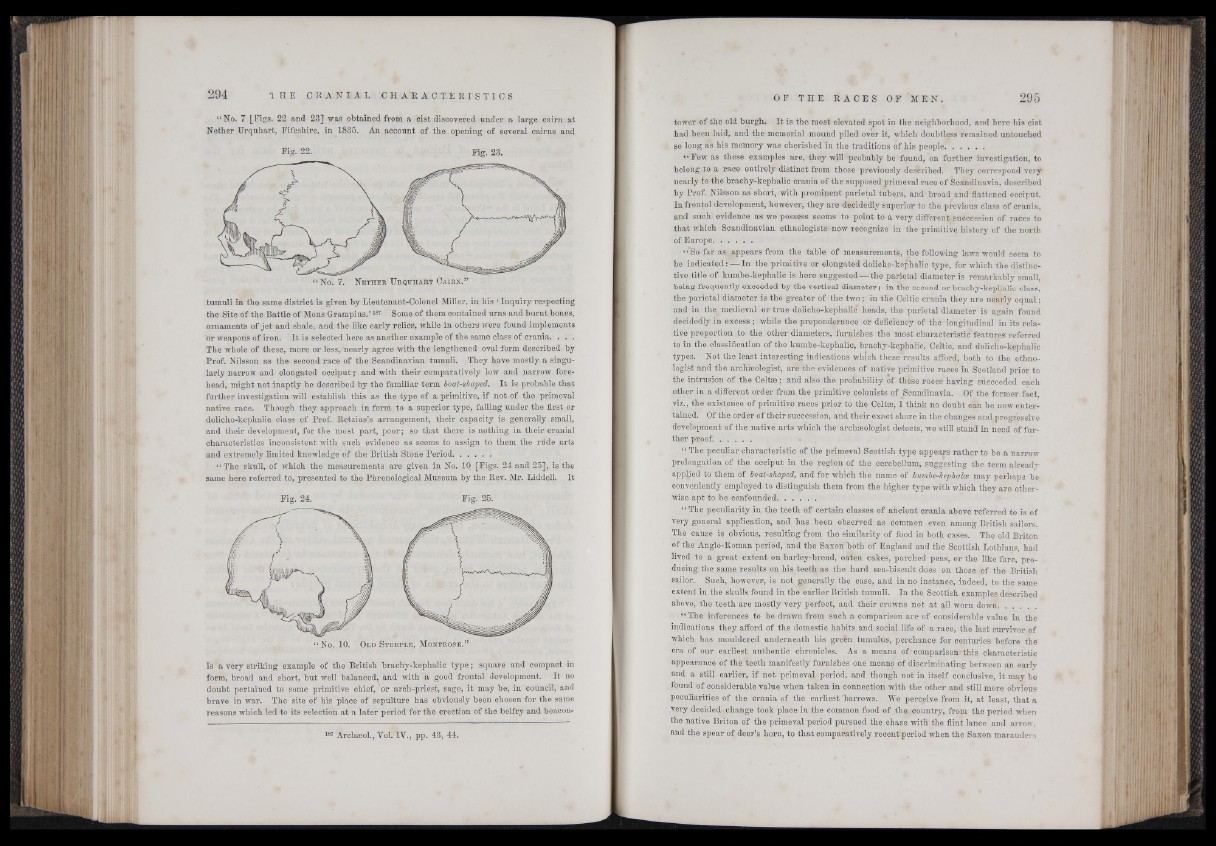

“ No. 7 [Figs-. 22 and 23] was obtained from a cist discovered under a large cairn at

Nether Urquhart, Fifeshire, in 1835. An account of the opening of several cairns and

Fig. 22. Fig. 23.

“ No. 7. N e t h e r U rq t jh a r t C a ir n . ”

tumuli in the same district is given by Lieutenant-Colonel Miller, in his 4 Inquiry respecting

the Site of the Battle of Mons Grampius.’187 Some of them contained urns and burnt bones,

ornaments of jet and shale, and the like early relics, while in others were found implements

or weapons of iron. It is selected here as another example of the same class of crania. . . .

The whole of these, more or less, nearly agree with the lengthened oval form described by

Prof. Nilsson as the second race of the Scandinavian tumuli. They have mostly a singularly

narrow and elongated occiput ;■ and with their comparatively low and narrow forehead,

might not inaptly be described by the familiar term boat-shaped. It is probable that

further investigation will establish this as the type of a primitive, if not of the primeval

native race. Though they approach in form to a superior type, falling under thé first or

dolicho-kephalic class of Prof. Retziùs’s arrangement, their capacity is generally small,

and their development, for the most part, poor; so that there is n,othing in their cranial

characteristics inconsistent with such evidence as seems to assign to them the rude arts

and extremely limited knowledge of the British Stone Period. . . . . .

“ The skull,.of which the measurements are given in No. 10 [Figs. 24 and 25], is the

same here referred to, presented to the Phrenological Museum by the Rev. Mr. Liddell. It

Fig. 24. Fig. 25.

“ No. 10. Ol d S t e e p l e , M o n t r o s e . ”

is a very striking example of the British brachy-kephalic type; square and compact in

form, broad and short, but well balanced, and with a good frontal development. It no

doubt pertained to some primitive chief,' or arch-priest, sage, it may be, in council, and

brave in war. The site of his place of sepulture has obviously been chosen for the same

reasons which led to its selection at a later period for the erection of the belfry and beacon--

787 Archæol., Vol. IY., pp. 43, 44.

tower of the old burgh. It is the most elevated spot in the neighborhood, and here his cist

had been laid, and the memorial mound piled over it, which doubtless remained untouched

so long as his memory was cherished in the traditions of his people. . . . . .

“ Few as these examples are, they will probably be found, on further investigation, to

belong-to a race entirely distinct from those previously described. They correspond very

nearly fo the brachy-kephalic crania of the supposed primeval race of Scandinavia, described

by Prof. Nilsson as short, with prominent parietal tubers, and broad and flattened occiput.

In frontal development, however, they are decidedly superior to the previous class of crania,

and such evidence as we possess seems to point to a very different succession of races to

that which Scandinavian- ethnologists now recognize in the primitive history of the north

of Europe. . . . . .

“*So>far as appears from the table of measurements, the following laws would seem to

be indicated: — In the primitive or elongated dolicho-kephalic type, for which the distinctive

title of kumbe-kephalic is here suggested-— the parietal diameter is remarkably small,

being frequently exceeded by the vertical diameter; in the second or brachy-kephalic class,

the parietal diameter is the greater of the two; in the Celtic crania they are nearly equal;

and in the medieval or true dolicho-kephalic heads, the parietal diameter is again found

decidedly in excess; while the preponderance or deficiency of the longitudinal in its relative

proportion to the other diameters, furnishes the most characteristic features referred

to in the classification of the kumbe-kephalic, brachy-kephalic, Celtic, and dolicho-kephalic

types. Not the least interesting indications which these results afford, both to the ethnologist

and the archaeologist, aré the evidences of native primitive races in Scotland prior to

the intrusion of the Celtae; and also the probability of these races having succeeded each

other in a different order from the primitive colonists of Scandinavia. Of the former fact

viz., the existence of primitive races prior to the Celt®, I think no doubt can be now entertained.

Of the order of their succession, and their exact share in the changes and progressive

development of the native arts which the archaeologist detects, we still stand in need of further

proof. . . . . .

“ The peculiar characteristic of the primeval Scottish type appears rather to be a narrow

prolongation of the occiput in the region of the cerebellum, suggesting the term already

appjjed to them of boat-shaped, and for which the name of kumbe-hephalce may perhaps be

conveniently employed-to distinguish them from the higher type with which they are otherwise

apt to be confounded.................

“ The peculiarity in the teeth of certain classes of ancient crania above referred to is of

very general application, and has been observed as common even among British sailors.

The Cause is obvious, resulting from the similarity of food in both cases. The old Briton

of the Anglo-Roman period, and the Saxon both of England and the Scottish Lothians, had

lived to a great extent on barley-bread, oaten cakes, parched peas, or the like fare, producing

the same results on his teeth as. the hard sea-biscuit does on those .of the British

sailor. Such, however, is not generally the case, and in no instance, indeed, to the same

extent in the skulls found in the earlier British tumuli. In the Scottish examples described

above, the teeth are mostly very perfect, and their crowns not at all worn down.................

“ The" inferences to be drawn from such a comparison are of considerable value in the

indications they afford of the domestic habits and social life of a race, the last survivor of

which has mouldered underneath his grebn tumulus, perchance for centuries before the

era of our earliest authentic chronicles. As a means of'comparison this characteristic

appearance of the teeth manifestly furnishes one means of discriminating between an early

and a still earlier, if not primeval - period, and though not in itself conclusive, it may be

found of considerable value when taken in connection with the other and still more obvious

peculiarities of the crania of the earliest ‘barrows. We percpive from it, at least, that a

very decided change took place in the common food of the country, from the period when

the native Briton of the primeval period pursued the chase with the flint lance and arrow,

and the spear of deer’s horn, to that comparatively recent period when the Saxon marauders