nationalities.2 But, whilst you judiciously selected the most characteristic

reliefs of Egypt and Assyria from the classical works of

Champollion, Rosellini, Eepsius, Botta, and Bayard ; all Etruscan,

Roman, Hindoo, and American antiquities were excluded from the

“ Types;” and I felt somewhat disappointed when I found, that as to

your Greek representations you were altogether mistaken. You

published, on the whole, five busts3 belonging strictly to the times

and nations of classical antiquity, but there is scarcely one among

them on which sound criticism could bestow an unconditional

approval.

You may find that I am rather hard upon you, as even your critic

in the Athenoeum Français4 objected only to one of them. Still, amicus

H ott, amicus Gliddon, sed magis arnica veritas ; and X hope that

if you have the patience to read my letter with attention, you will

yourselves plead guilty.

The busts which I am to review are the alleged portraits of B ycur-

gus, the Spartan legislator, of A l exander the Great, of E ratosth

en es , of H a nnibal, and of J uba I . , king of Humidia.

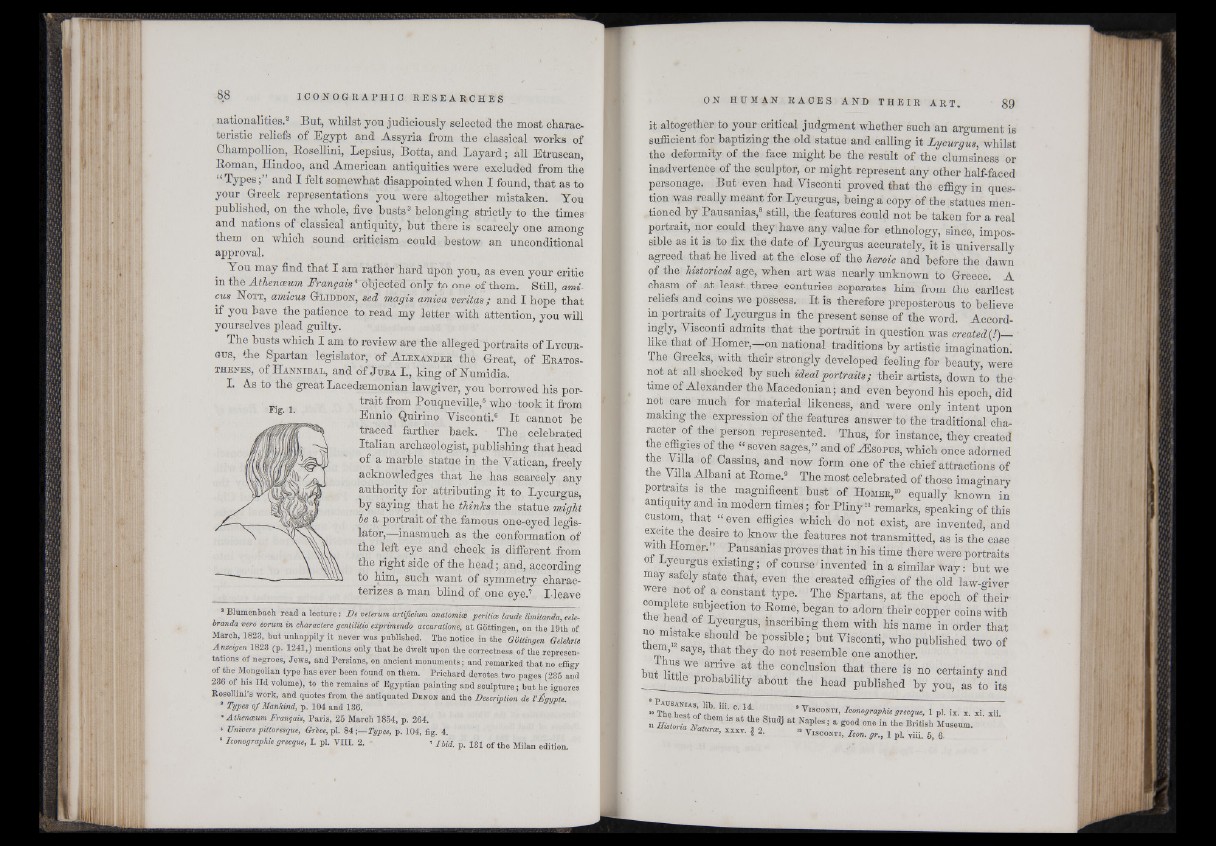

I. As to the great Bacedæmonian lawgiver, you borrowed his por-

Fi j trait from Pouqueville,5 who took it from

Ennio Quirino Visconti.6 It cannot be

traced farther back. The celebrated

Italian archæologist, publishing that head

of a marble statue in the Vatican, freely

acknowledges that he has scarcely any

authority for attributing it to Bycurgus,

by saying that he thinks the statue might

le a portrait of the famous one-eyed legislator,—

inasmuch as the conformation of

the left eye and cheek is different from

the right side of the head; and, according

to him, such want of symmetry characterizes

a man blind of one eye.7 I-leave

! Kumenbach read a lecture: De veterum artifieium anatomies periiioe laude limitanda, cele-

branda vero eorum in charactere gentilttio exprimendo accuratione, at Gottingen, on the 19th of

March, 1823, but unhappily it never was published. The notice in the Gottingen Gelehrte

Anzeigen 1823 (p. 1241,) mentions only that he dwelt upon the correctness of the representations

of negroes, Jews, and Persians, on ancient monuments ; and remarked that no effigy

of the Mongolian type has ever been found on them. Prichard devotes two pages (235 and

236 of his lid volume), to the remains of Egyptian painting and sculpture ; but he ignores

Rosellim’s work, aid quotes from the antiquated D e n o n and the Description de VÉgypte.

* Types of Mankind, p. 104 and 186.

'Athenoeum Français, Paris, 25 March 1854, p. 264.

‘ Univers pittoresque, Grice, pi. 84 ;—Types, p. 104, fig. 4.

• Iconographie grecque, I. pl. VIII. 2. - ’ Ibid. p. 131 of the Milan edition.

it altogether to your critical judgment whether such an argument is

sufficient for baptizing the old statue and calling it Lycurgus, whilst

the deformity of the face might be the result of the clumsiness or

inadvertence of the sculptor, or might represent any other half-faced

personage. But even had Visconti proved that the effigy in question

was really meant for Bycurgus, being a copy of the statues mentioned

by Pausanias,8 still, the features could not be taken for a real

portrait, nor could they have any value for ethnology, since, impossible

as it is to fix the date of Bycurgus accurately, it is universally

agreed that he lived at the close of the heroic and before the dawn

of the historical age, when art was nearly unknown to Greece. A

chasm of at least three centuries separates him from the earliest

reliefs and coins we possess. It is therefore preposterous to believe

in portraits of Bycurgus in the present sense of the word. Accordingly*

Visconti admits that the portrait in question was created (!)__

hke that of Homer,—on national traditions by artistic imagination.

The Greeks, with their strongly developed feeling for beauty, were

not at all shocked by such ideal 'portraits; their artists, down to the

time of Alexander the Macedonian; and even beyond his epoch, did

not care much for material likeness, and were only intent upon

making the expression of the features answer to the traditional character

of the person represented. Thus, for instance, they created

the effigies of the “ seven sages,” and of ^sopus, which once adorned

I?6 H H Cassms’ and now form one of the chief attractions of

the Villa Albani at Rome.9 The most celebrated of those imaginarv

portraits is the magnificent bust of Homer,10 equally known in

antiquity and in modem times; for Pliny11 remarks, speaking of this

custom that “ even effigies which do not exist, are invented, and

^cite the desire to know the features not transmitted, as is the case

wnn tlomer. ’ Pausanias proves that in his time there were portraits

ot Bycurgus existing; of course invented in a similar way: but we

may safely state that, even the created effigies of the old law-giver

were not of a constant type. The Spartans, at the epoch of their

complete subjection to Rome, began to adorn their copper coins with

“ m inscribing them with his name in order that

1 3 S P E possible; tut Visconti, who published two of

’ ys>tbat they do not resemble one another.

but Z Z 1116 conclusion tbat there is no certainty and

________ probability about the head published by you, as to its

* •^•^SANIAS, lib. iii i» 14. g tt r

10 Thebftst nf I Ü H VISCONTI, Iconographie grecque, 1 pl. ix . x. x i. x ii.

-M B È & 8 5 jatSK3! agood- , x x x v . g 2. Visconti, Icon, gr., 111 1 ptLh evBiiir.i t5i,s h6M- — ■