to this current opinion on the relative modernness of Egyptian

statuary, were then entertained chiefly by Mr. Birch— who had

already classified, as appertaining to the Old Empire, various archaic

fragments in the British Museum,—by Chev. Lepsius, when publishing

a few mutilated statues among the early dynasties of the Denk-

mâler,—and by the Yicomte de Bougé, who wrote in 1852 ;® “ Trois

statues de la galerie du Louvre (nos. 36, 37, 38) présentent un excellent

spécimen de la sculpture de ces premiers âges. Dans ces morceaux,

uniques jusqu’ici et par conséquent inestimables, le type des

hommes a quelque chose de plus trapu et de plus rude ; la pose est

d’une grande simplicity ; quelques parties rendent la nature avec

vérité ; mais l’on sent déjà qu’une loi hiératique a réglé les attitudes

et va ravir aux artistes une partie précieuse de leur liberté.”

It must, therefore, be gratifying to the authors of the precursory

volume to the present, to find their doctrine, “ that the primitive

Egyptians were nothing more nor less than — EGYPTIANS,”00 so

incontestably confirmed by a group of statues' which did not reach

Paris for six months after the publication of their researches ; and

we may now rejoice with those archaeologists, whose acumen had

already foreshadowed the discovery of beautiful statuary belonging

to the early days of the pyramids, that, henceforward, the series of

Egyptian art continues, in an unbroken chain, from the 35th century

B. C. down to long after the Christian era.

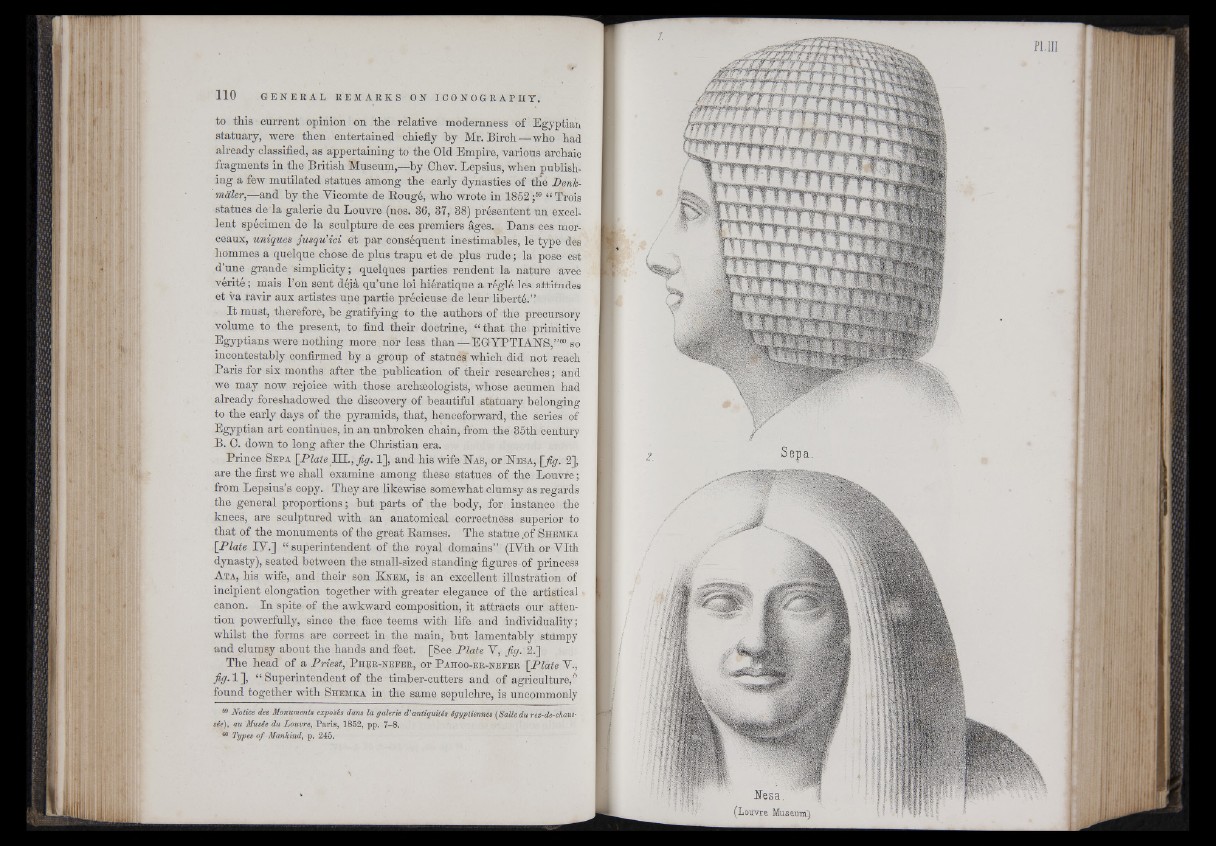

Prince S e pa [Plate TH., jig. 1], and his wife H a s , or B e sa , [Jig. 2],

are the first we shall examine among these statues of the Louvre ;

from Lepsius’s copy. They are likewise somewhat clumsy as regards

the general proportions; but parts of the body, for instance the

knees, are sculptured with an anatomical correctness superior to

that of the monuments of the great Bamses. The statue .of S hemka

{Plate iy .] “ superintendent of the royal domains” (IVth or Vlth

dynasty), seated between the small-sized standing figures of princess

A ta, his wife, and their son E n e m , is an excellent illustration of

incipient elongation together with greater elegance of the artistical

canon. In spite of the awkward composition, it attracts our attention

powerfully, since the face teems with life and individuality ;

whilst the forms are correct in the main, but lamentably stumpy

and clumsy about the hands and feet. [See Plate Y, fig. 2.]

The head of a Priest, P h r r -n e e e r , or P ahoo-e r -n e p e r [Plate V .,

fig. 1], “ Superintendent of the timber-cutters and of agriculture,’’’

found together with S hem k a in the same sepulchre, is uncommonly

59 Notice des Monuments exposés dans la galerie d’antiquités égyptiennes (Salle du rez-de-chaussée),

au Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1852, pp. 7—8.

60 Types of Mankind, p. 245.