9.

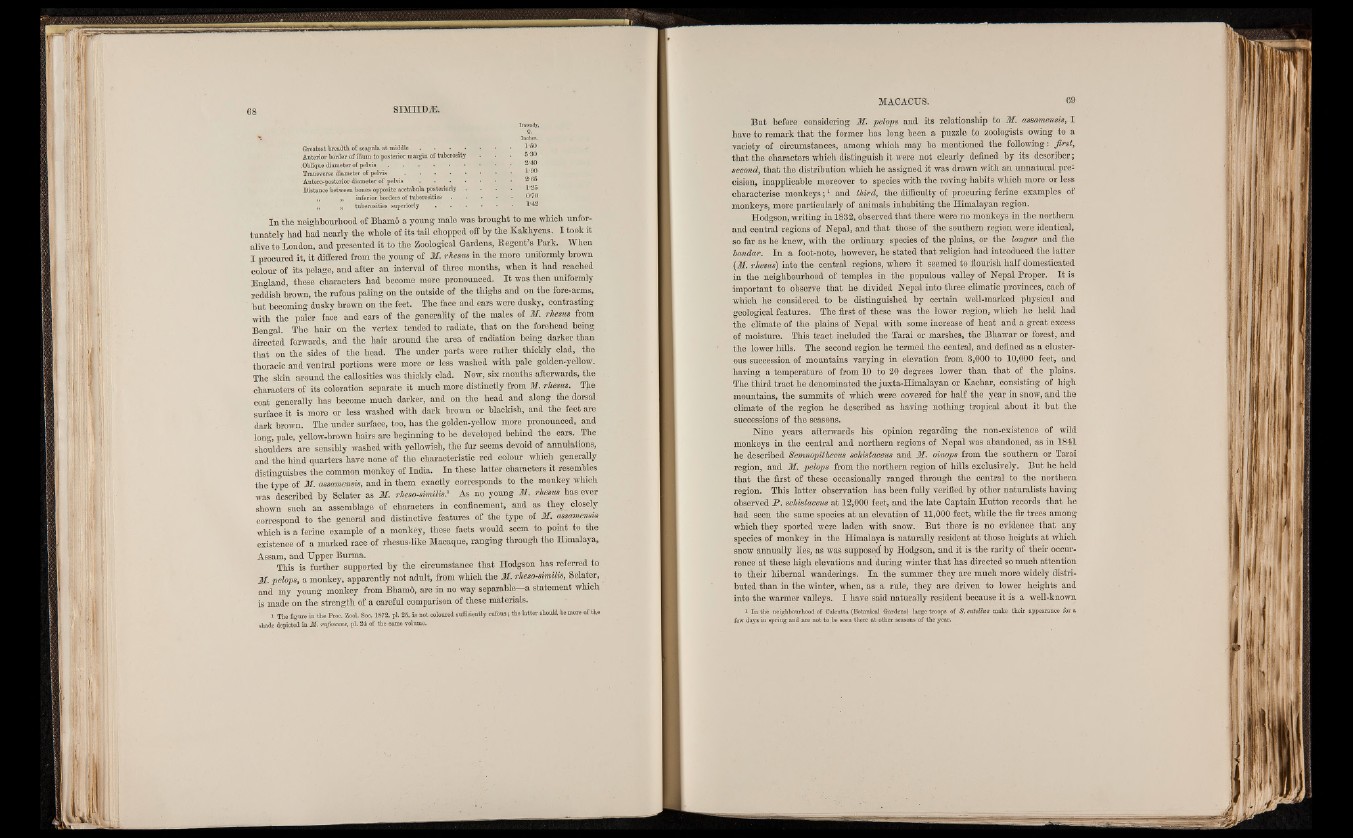

Inches.

Greatest breadth of scapula at middle , ■ * . ' * ' ' ^

Anterior border of ilium to posterior margin of tuberosity . • • 5‘30

.Oblique diameter of pelvis ......... ........................................................... .........

Transverse diameter of p e l v i s ................................................. ................... 190

Antero-posterior diameter o f p e l v i s ........................................ ................... ^'65

Distance between bones opposite acetabula posteriorly . . . . 1‘25

„ • „ inferior borders of tuberosities . . . . • 0'70

„ „ tuberosities superiorly . . . - • • 1'42

In the neighbourhood of Bhamô a young male was brought to me which unfortunately

had had nearly the whole of its tail chopped off by the Kakhyens. I took it

alive to London, and presented it to the Zoological Gardens, Regent's Park. When

I prooured it, it differed from the young of M. rhesus in the more uniformly brown

colour of its pelage, and after an interval of three months, when it had reached

England, these characters had become more pronounced. 1 I t was then uniformly

reddish brown, the rufous paling on the outside of the thighs and on the fore-arms,

bu t becoming dusky brown on the feet. The face and ears were dusky, contrasting

with the paler face and ears of the generality of the males of M. rhesus from

Bengal. The hair on the vertex tended to radiate, that on the forehead being

directed forwards, and the hair around the area of radiation being darker than

that on the sides of the head. The under parts were rather thickly clad, the

thoracic and ventral portions were more or less washed with pale golden-yellow.

The skin around the callosities was thickly clad. Now, six months afterwards, the

characters of its coloration separate it much more distinctly from M. rhesus. TJie

coat generally has become much darker, and on the head and along the dorsal

surface it is more or less washed with dark brown or blackish, and the feet are

dark brown. The under surface, too, has the golden-yellow more pronounoed, and

long, pale, yellow-brown hairs are beginning to be developed behind the ears. The

shoulders are sensibly washed with yellowish, the fur seems devoid of annulations,

and the hind quarters have none of the characteristic red colour which generally

distinguishes the common monkey of India. In these latter characters it resembles

the type of M. assamensis, and in them exactly corresponds to the monkey which

was described by Sclater as M. rheso-smilis! As no young M. rhesus has ever

shown such an assemblage of characters in confinement, and as they_ closely

correspond to the general and distinctive features of the type of M. assamensis

which is a ferine example of a monkey, these facts would seem to point to the

existence of a marked race of rhesus-like Macaque, ranging through the Himalaya,

Assam, and Upper Burma.

This is further supported by the circumstance that Hodgson has referred to

M. pelops, a monkey, apparently not adult, from which the M. rheso-similis, Sclater,

and my young monkey from Bhamô, are in no way separable—a statement which

is made on the strength of a careful comparison of these materials.

l The figure in the Proo. Zool. See. 1872, p i 25, is not coloured sufficiently rufous i the latter should be more of the

shade depicted in M . rvfescens, pi. 24 of the same volume.

But before considering M. pelops and its relationship to M. assamensis, I

have to remark th a t the former has long been a puzzle to zoologists owing to a

variety of circumstances, among which may be mentioned the following : first,

that the characters which distinguish it were not clearly defined by its desçriber ;

second, that the distribution which he assigned it was drawn with an unnatural precision,

inapplicable moreover to species with the roving habits which more or less

characterise monkeys ; 1 and third, the difficulty of procuring ferine examples of

monkeys, more particularly of animals inhabiting the Himalayan region.

Hodgson, writing in 1832, observed that there were no monkeys in the northern

and central regions of Nepal, and that those of the southern region were identical,

so far as he knew, with the ordinary species of the plains, or the lamgur and the

bandar. In a foot-note, however, he stated that religion had introduced the latter

(M. rhesus) into the central regions, where it seemed to flourish half domesticated

in the neighbourhood of temples in the populous valley of Nepal Proper. I t is

important to observe that he divided Nepal into three climatic provinces, each of

which he considered to be distinguished by certain well-marked physical and

geological features. The first of these was the lower region, which he held had

the ciimate of the plains of Nepal with some increase of heat and a great excess

of moisture. This tract included the Tarai or marshes, the Bhawar or forest, and

thé lower hills. The second region he termed the central, and defined as a cluster-

ous succession of mountains varying in elevation from 3,000 to 10,000 feet, and

having a temperature of from 10 to 20 degrees lower than that of the plains.

The third tract he denominated the juxta-Himalayan or Kachar, consisting of high

mountains, the summits of which were covered for half the year in snow, and the

climate of the region he described as having nothing tropical about it but the

successions of the seasons.

Nine years afterwards his opinion regarding the non-existence of wild

monkeys in the central and northern regions of Nepal was abandoned, as in 1841

he described Semnopithecus schistaceus and M. omops from the southern or Tarai

region, and M. pelops from the northern region of hills exclusively. But he held

that the first of these occasionally ranged through the central to the northern

region. This latter observation has been fully verified by other naturalists having

observed P . schistaceus at 12,000 feet, and the late Captain Hutton records that he

had seen the same species a t an elevation of 11,000 feet, while the fir trees among

which they sported were laden with snow. But there is no evidence tha t any

species of monkey in the Himalaya is naturally resident a t those heights a t which

snow annually lies, as was supposed by Hodgson, and it is the rarity of their occurrence

at these high elevations and during winter that has directed so much attention

to their hibernal wanderings. In the summer they are much more widely distributed

than in the winter, when, as a rule, they are driven to lower heights and

into the warmer valleys. I have said naturally resident because it is a well-known

1 In the neighbourhood of Calcutta (Botanical Gardens) large troops of 8. entellus make their appearance for a

few days in spring and are not to be seen there at other seasons of the year.