large cul de sac, which projects upwards along the side of the oesophagus, and internally

its walls axe seen to be thick and to he quite different from the remainder

of the stomachic wall. To the right of the oesophagus, there is a rounded

eminence in the position of the sack which occurs in the stomach of the voles,

and which probably will be detected also in fresh stomachs of Siphneus. Immediately

below, and to the right of the swelling, there is a contraction which marks

off the left limit of the pre-pyloric sack which is cylindrical and elongated.

From this contraction to the base of the left cul de sac is the great cavity

of the stomach.

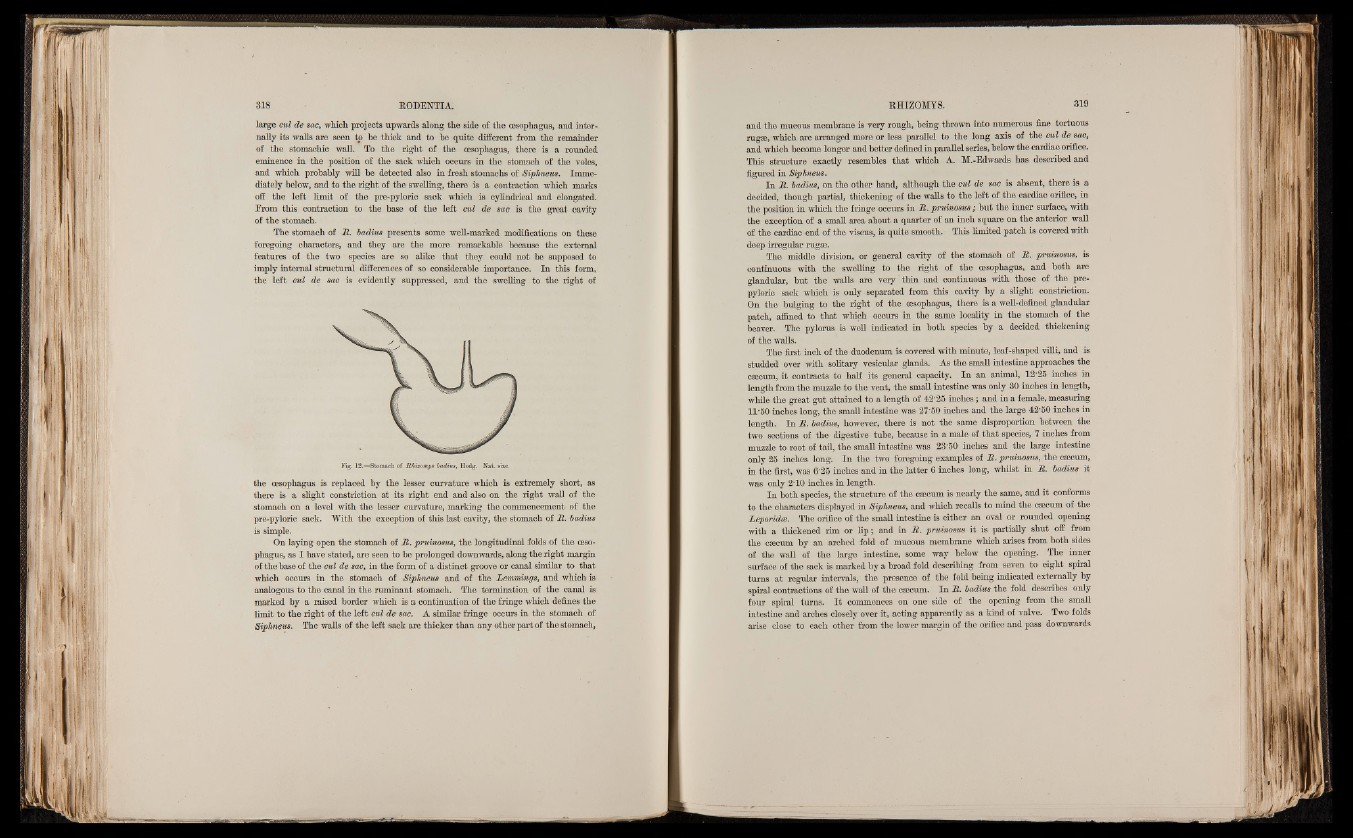

The stomach of R. badius presents some well-marked modifications on these

foregoing characters, and they are the more remarkable because the external

features of the two species are so alike that they could not be supposed to

imply internal structural differences of so considerable importance. In this form,

the left cul de sac is evidently suppressed, and the swelling to the right of

Fig. 12.—Stomach of Rkizomys badius, Hodg. Nat. size.

the oesophagus is replaced by the lesser curvature which is extremely short, as

there is a slight constriction at its right end and also on the right wall of the

stomach on a level with the lesser curvature, marking the commencement of the

pre-pyloric sack. With the exception of this last cavity, the stomach of R. badius

is simple.

On laying open the stomach of R. prumosus, the longitudinal folds of the oesophagus,

as I have stated, are seen to be prolonged downwards, along the right margin

of the base of the cul de sac, in the form of a distinct groove or canal similar to that

which occurs in the stomach of SipJmeus and of the Lemmings, and which is

analogous to the canal in the ruminant stomach. The termination of the canal is

marked by a raised border which is a continuation of the fringe which defines the

limit to the right of the left cul de sac. A similar fringe occurs in the stomach of

Siphneus. The walls of the left sack are thicker than any other part of the stomach,

and the mucous membrane is very rough, being thrown into numerous fine tortuous

rugae, which are arranged more or less parallel to the long axis of the cul de sac,

and which become longer and better defined in parallel series, below the cardiac orifice.

This structure exactly resembles that which A. M.-Edwards has described and

figured in Siphneus.

In R. badius, on the other hand, although the cul de sac is absent, there is a

decided, though partial, thickening of the walls to the left of the cardiac orifice, in

the position in which the fringe occurs in R. prumosus ; but the inner surface, with

the exception of a small area about a quarter of an inch square on the anterior wall

of the cardiac end of the viscus, is quite smooth. This limited patch is covered with

deep irregular rugae.

The middle division, or general cavity of the stomach of R. prumosus, is

continuous with the swelling to the right of the oesophagus, and both are

glandular, but the walls are very thin and continuous with those of the prepyloric

sack which is only separated from this cavity by a slight constriction.

On the bulging to the right of the oesophagus, there is a well-defined glandular

patch, affined to that which occurs in the same locality in the stomach of the

beaver. The pylorus is well indicated in both species by a decided thickening

of the walls.

The first inch of the duodenum is covered with minute, leaf-shaped villi, and is

studded over with solitary vesicular glands. As the small intestine approaches the

caecum, it contracts to half its general capacity. In an animal, 12*25 inches in

length from the muzzle to the vent, the small intestine was only 30 inches in length,

while the great gut attained to a length of 42*25 inches; and in a female, measuring

11*50 inches long, the small intestine was 27*50 inches and the large 42*50 inches in

length. In R. badius, however, there is not the same disproportion between the

two sections of the digestive tube, because in a male of that species, 7 inches from

muzzle to root of tail, the small intestine was 23*50 inches and the large intestine

only 25 inches long. In the two foregoing examples of R. prumosus, the caecum,

in the first, was 6*25 inches and in the latter 6 inches long, whilst in R. badius it

was only 2*10 inches in length.

In both species, the structure of the caecum is nearly the same, and it conforms

to the characters displayed in Siphneus, and which recalls to mind the caecum of the

Leporidce. The orifice of the small intestine is either an oval or rounded opening

with a thickened rim or lip ; and in R. pruinosus it is partially shut off from

the caecum by an arched fold of mucous membrane which arises from both sides

of the wall of the large intestine, some way below the opening. The inner

surface of the sack is marked by a broad fold describing from seven to eight spiral

turns at regular intervals, the presence of the fold being indicated externally by

spiral contractions of the wall of the caecum. In R. badius the fold describes only

four spiral turns. I t commences on one side of the opening from the small

intestine and arches closely over it, acting apparently as a kind of valve. Two folds

arise close to each other from the lower margin of the orifice and pass downwards