contraction of the bodies into a well-marked ridge occurs in these rodents in the

sacral region. The sacrum, unlike that of the Muridce, is very compact and

strong, the pleurapophyses being considerably expanded and broadly applied to the

ilium.

In R. badius, Hodgson, only two vertebrae are applied to the ilium, the third

vertebra, although assuming the form of a sacral, is quite free and followed by

another similar segment; so that if these two are regarded as pseudo-sacral, there

are only sixteen caudal vertebrae. In R. prumosus, the third sacral vertebra

partially touches the ilium, and is amalgamated posteriorly with a pseudo-sacral

vertebral element resembling itself; so that, leaving these out of view, there

are 19 caudals. The pseudo-sacral element exists to give support to the thickened

base of the tail. In these respects the skeleton of Rhizomys resembles that of

Siphneus.

Broad transverse processes are well developed on the first five caudal vertebrae, but

they disappear on the seventh, or are represented by a lateral ridge, as far back as the

seventeenth. In R. badius, Hodgson, the transverse processes are distinctly visible as

far back as the ninth vertebra, and their rudiments can be traced even to the thirteenth.

In both these species, these processes are horizontally expanded. Also in both, the

neural canal is perfect on the first four true caudals, and hsemapophyses are developed

from the sixth to the twelfth vertebra. Metapophyses occur from the first to the

fifth caudal, and are well developed. The bodies diminish slightly in length from the

first to the fifth caudal, beyond which they lengthen to the ninth, after which they

again decrease in length. . Eight ribs are directly attached to the sternum, which

consists of seven to eight osseous pieces, the last long and narrow, and occasionally

amalgamating with the smallest of the segments which immediately precedes it. I t is

capped by a broad halbert-shaped xyphoid cartilage resembling the manubrium

in form. The manubrium at its lower end, and the various segments of the meso-

stemum, have each a well-marked epiphysis, and the sternal tips of the rib cartilages

are capped with little ossicles in JR. badius. The clavicle is strong and slightly

outwardly and downwardly curved in its inner half, this head of the bone being large

and rounded, while its acromial end expands, and is flattened from above downwards.

In one skeleton of R. prumosus a small ossicle occurs at the sternal end of the

clavicle. In R. badius there are only six sternal segments and seven sternal ribs.

The manubrium in both species resembles that of Siphneus, and is short and much

expanded, so much so that it is broader than long, and is rounded anteriorly; hence

it is very different from the form of this bone in Bathyergus and Georychus. I t

has a ventral ridge, rather well marked in one female, but nearly obsolete in a male

skeleton. In a female, also, the manubrium is longer than -broad, the lower end or

shaft being well defined, while in a male it is extremely short—nay, almost

absent. Although these two bones are markedly distinct, there can be no doubt

of the specific identity of the two sexes, as they were both killed together.

The manubrium in a female of R. badius has the same form as in the male

of both species.

The scapula of R. prumosus and of R. badius are essentially like that of Siphneus,

and when they are described as only more elongated and broader across the neck of

the bone than in ordinary rats, some idea of their form will have been conveyed. The

acromio-scapular notch is not so deep as in the rat, and the acromion is more

forwardly projected than in that animal and has great expansion.

The os imotmnatum conforms to the Arvicoline type, but the thyroid foramen is

much longer than in Siphneus, and the pubic and ischial bones are weaker and less

expanded, the former being reduced to a narrow rod. There are also certain

remarkable differences between the pelves of these two forms. In R. badius the

thyroid foramen is quite as small as in Siphneus, and the symphysis pubis,

which is rather deep in R . prumosus, is the very opposite in the former species.

In both, anchylosis has taken place through the intervention of a triangular

epiphysis, but, even with the aid of this, the symphysis is not so deep as in JMus

decumanus.

The sexual characters of the pelves of these species are very well defined, the

transverse breadth of the symphysis being much greater in the female than in the

male.

The skull has been described by Temminck, and its general characters indicated

by A. M.-Edwards, so that nothing remains to be said under this head, except

that the periotic bullae are well developed on the posterior aspect of the skull, behind

the auditory osseous tube. Three prominent transverse grooves occur on the anterior

portion of the palate, immediately before the molars, and are succeeded by four much

more obscure furrows between the teeth.

In a young example of R. prumosus, Blyth, the incisor teeth are well exposed,

but none of the upper or under molars have pierced the mucous covering of the

jaw.

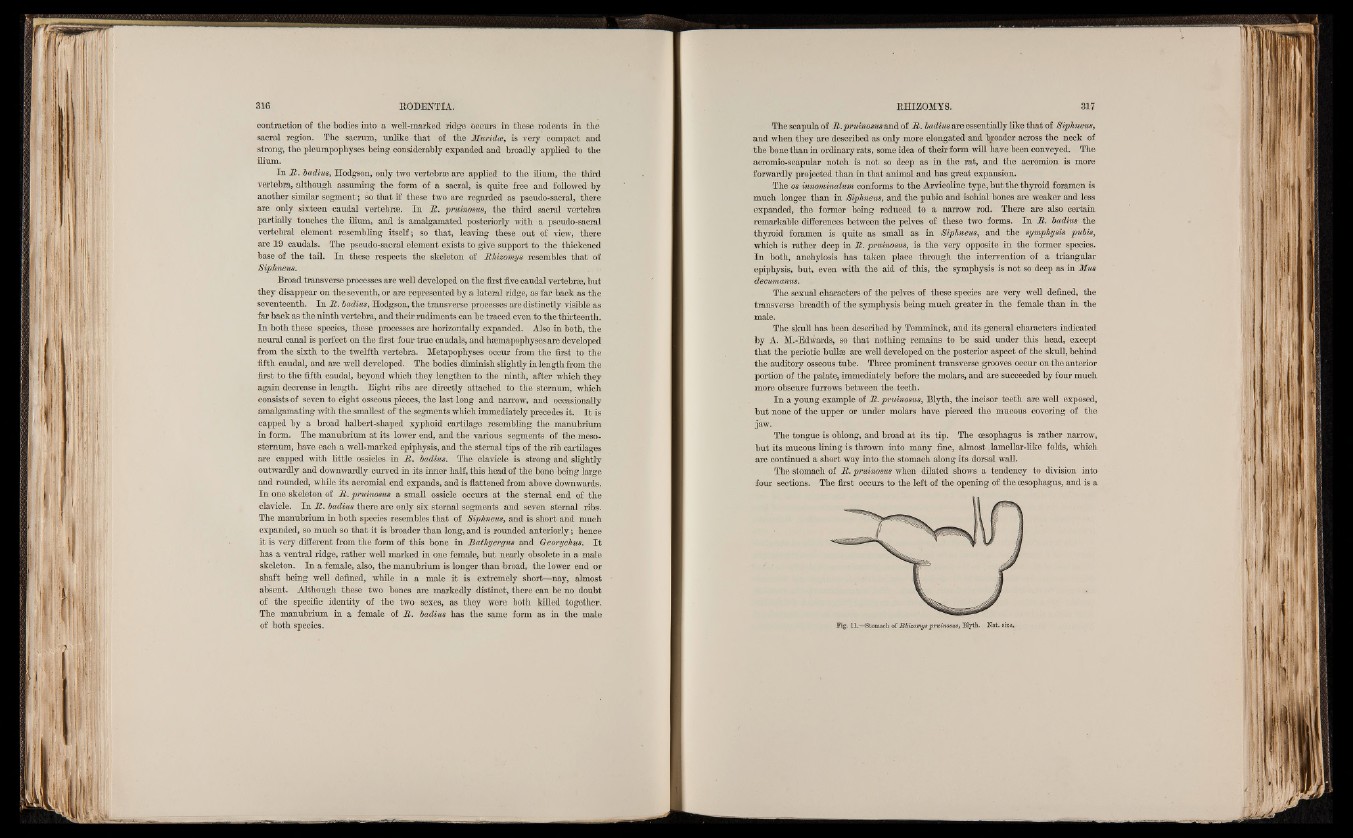

The tongue is oblong, and broad at its tip. The oesophagus is rather narrow,

but its mucous lining is thrown into many fine, almost .lamellar-like folds, which

are continued a short way into the stomach along its dorsal wall.

The stomach of R. prumosus when dilated shows a tendency to division into

four sections. The first occurs to the left of the opening of the oesophagus, and is a

Fig. 11.—Stomach of Rhizomys pruinosus, Blyth. Nat. size.