178. 179. 180. D e lichamelijke opvoe-

ding en ontwikeling bij het onderwijs.

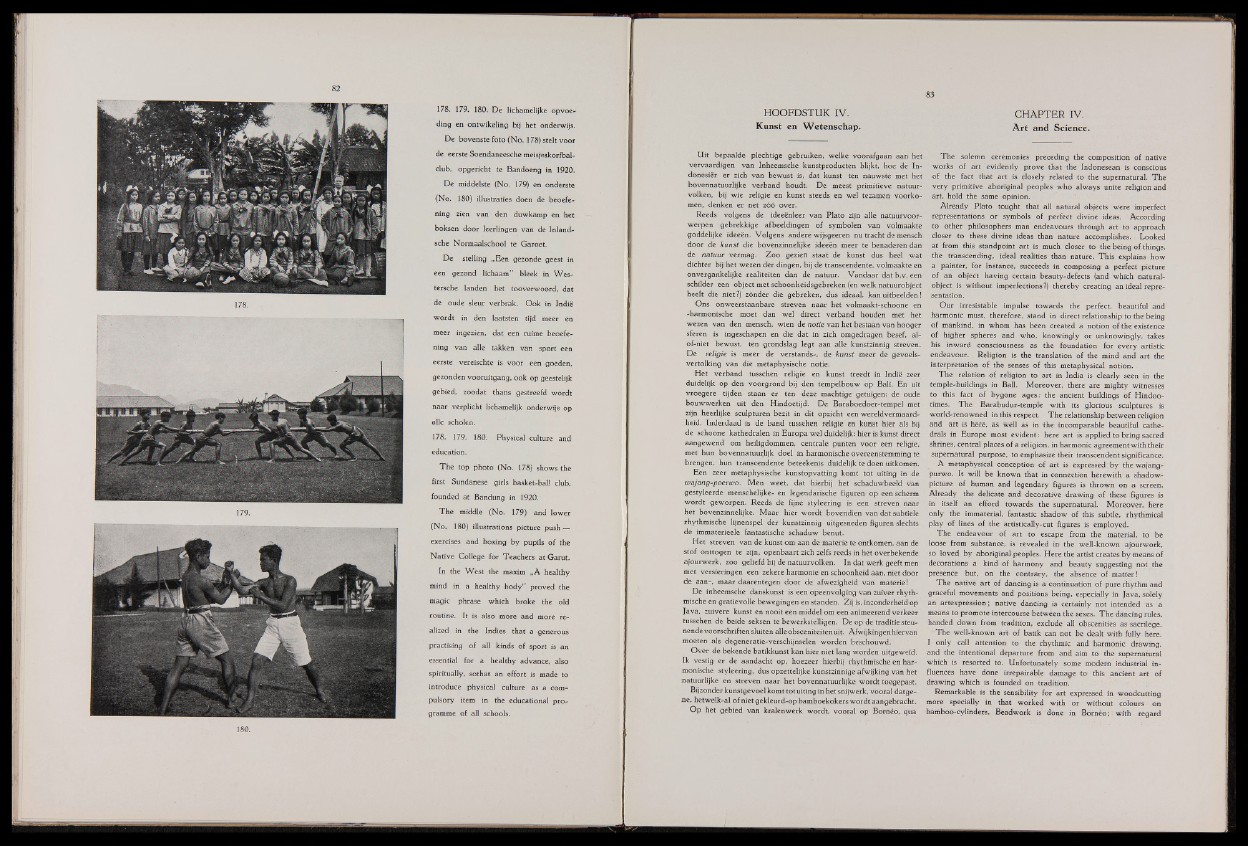

D e bovenste £oto (No . 178) stelt voor

de eerste Soendaneesche meisjeskorfbal-

club, opgericht te Bandoeng in 1920.

De middelste (No. 179) en onderste

(No. 180) illustraties doen de beoefe-

ning zien van den duwkamp en het

boksen door leerlingen van de Inland-

sche Normaalschool te Garoet.

De stelling „Een gezonde geest in

een gezond lichaam” bleek in W e s-

tersche landen het tooverwoord, dat

de oude sleur verbrak. Ook in Indie

wordt in den laatsten tijd meer en

meer ingezien, dat een ruime beoefe-

ning van alle takken van sport een

eerste vereischte is voor een goeden,

gezonden vooruitgang, ook op geestelijk

gebied, zoodat thans gestreefd wordt

naar verplicht lichamelijk onderwijs op

alle scholen.

178. 179. 180. Physical culture and

education.

The top photo (No. 178) shows the

first Sundanese girls basket-ball club,

founded at Bandung in 1920."

The middle (No . 179) and lower

(No . 180) illustrations picture push —

exercises and boxing by pupils o f the

Native College for Teachers at Garut.

In the W e st the maxim „A healthy

mind in a healthy body’’ proved the

magic phrase which broke the old

routine. It is also more and more realized

in the Indies that a generous

practising of all kinds of sport is an

essential for a healthy advance, also

spiritually, sothat an effort is made to

introduce physical culture as a compulsory

item in the educational programme

o f all schools.

HOOFDSTUK IV.

Kunst en We tense hap.

U it bepaalde plechtige gebruiken, welke voorafgaan aan het

vervaardigen van Inheemsche kunstproducten blijkt, hoe de Indonesier

er zieh van bewust is, dat kunst ten nauwste met het

bovennatuurlijke verband houdt. De meest primitieve natuur-

volken, bij wie religie en kunst steeds en wel tezamen voorko-

men, denken er net zóó over.

Reeds volgens de ideeénleer van Plato zijn alle natuurvoor-

werpen gebrekkige afbeeldingen o f Symbolen van volmaakte

goddelijke ideeén. Volgens andere wijsgeeren nu tracht de mensch

door de kunst die bovenzinnelijke ideeén meer te benaderen dan

de natuur vermag. Z o o gezien Staat de kunst dus heél wat

dichter bij het wezen der dingen, bij de transcendente, volmaakte en

onvergankelijke realiteiten dan de natuur. Vandaar dat b.v. een

schilder een object met schoonheidsgebreken (en welk natuurobject

heeft die niet?) zonder die gebreken, dus ideaal, kan uitbeelden!

Ons onweerstaanbare streven naar het volmaakt-schoone en

-harmonische moet dan wel direct verband houden met het

wezen van den mensch, wien de notie van het bestaan van hooger

sferen is ingeschapen en die dat in zieh omgedragen besef, al-

of-niet bewust, ten grondslag legt aan alle kunstzinnig streven.

De religie is meer de Verstands-, de kunst meer de gevoels-

vertolking van die metaphysische notie.

Het verband tusschen religie en kunst treédt in Indie zeer

duidelijk op den voorgrond bij den tempelbouw op Bali. En uit

vroegere tijden staan er ten deze mächtige getuigen: de oude

bouwwerken uit den Hindoetijd. D e Baraboedoer-tempel met

zijn heerlijke sculpturen bezit in dit opzicht een wereldvermaard-

heid. Inderdaad is de band tusschen religie en kunst hier als bij

de schoone kathedralen in Europa w el duidelijk: hier is kunst direct

aangewend om heiligdommen, centrale punten voor een religie,

met hun bovennatuurlijk doel in harmonische overeenstemming te

brengen, hun transcendente beteekenis duidelijk te doen uitkomen.

Een zeer metaphysische kunstopvatting komt tot uiting in de

wajang-poerwo. Men weet, dat hierbij het schaduwbeeld van

gestyleerde menschelijke- en legendarische figuren op eenscherm

wordt geworpen. Reeds de fijne styleering is een streven naar

het bovenzinnelijke. Maar hier wordt bovendien van dat subtiele

rhythmische lijnenspel der kunstzinnig uitgesneden figuren slechts

de immaterieele fantastische schaduw benut.

H et streven van de kunst om aan d e materie te ontkomen, aan de

stof onttogen te zijn, openbaart zieh zelfs reeds in het overbekende

ajourwerk, zoo geliefd bij de natuurvolken. In dat werk geeft men

met versieringen een zekere harmonie en schoonheid aan, niet door

de aan-, maar daarentegen door de afwezigheid van materie!

De inheemsche danskunst is een opeenvolging van zuiver rhythmische

en gratievolle bewegingen en standen. Zij is, inzonderheid op

Java, zuivere kunst en nooit een middel om een animeerend verkeer

tusschen de beide seksen te bewerkstelligen. De op de traditie steu-

nende voorschriften sluiten alle obsceniteiten tiit. Afwijkingen hiervan

moeten als degeneratie-verschijnselen worden beschouwd.

Over de bekende batikkunst kan hier niet lang worden uitgeweid.

Ik vestig er de aandacht op, hoezeer hierbij rhythmische en harmonische

styleering, dus opzettelijke kunstzinnige afwijking van het

natuurlijke en streven naar het bovennatuurlijke wordt toegepast.

Bijzonder kunstgevoel komt totuiting in het snijwerk, vooral datge-

ne, hetwelk-al o f niet gekleurd-op bamboekokers wordt aangebracht.

Op het gebied van kralenwerk wordt, vooral op Borneo, qua

CHAPTER IV.

Art and Science.

The solemn ceremonies preceding the composition of native

works o f art evidently prove that the Indonesean is conscious

o f the fact that art is closely related to the supernatural. The

very primitive aboriginal peoples who always unite religion and

art, hold the same opinion.

Already Plato tought that all natural objects were imperfect

representations or symbols o f perfect divine ideas. According

to other philosophers man endeavours through art ■ to approach

closer to these divine ideas than nature accomplishes. Looked

at from this standpoint art is much closer to the being o f things,

the transcending, ideal realities than nature, This explains how

a painter, for instance, succeeds in composing a perfect picture

o f an object having certain beauty-defects (and which natural-

object is without imperfections ?) thereby creating an ideal representation.

Our irresistable impulse towards the perfect, beautiful and

harmonic must, therefore, stand in direct relationship to the being

o f mankind, in whom has been created a notion o f the existence

o f higher spheres and who, knowingly or unknowingly, takes

his inward consciousness as the foundation for every artistic

endeavour. Religion is the translation o f the mind and art the

interpretation o f the senses of this metaphysical notion.

The relation o f religion to art in India is clearly seen in the

temple-buildings in Ball. Moreover, there are mighty witnesses

to this fact o f bygone ages: the ancient buildings o f Hindoo-

times. The Barabudur-temple with its glorious sculptures is

world-renowned in this respect. The relationship b etween religion

and art is here, as well as in the incomparable beautiful cathedrals

in Europe most evident: here art is-applied to bring sacred

shrines, central places o f a religion, in harmonic agreement with their

supernatural purpose, to emphasize their transcendent significance.

A metaphysical conception o f art is expressed by thewajang-

purwo. It will be known that in connection herewith a shadow-

picture o f human and legendary figures is thrown on a screen.

Already the delicate and decorative drawing o f these figures is

in itself an efford towards the supernatural. Moreover, here

only the immaterial, fantastic shadow o f this subtle, rhythmical

play of lines o f the artistically-cut figures is employed.

The endeavour o f art to escape from the material, to be

loose from substance, is revealed in the well-known ajourwork,

so loved by aboriginal peoples. Here the artist creates by means o f

decorations a kind o f harmony and beauty suggesting not the

presence but, on the contrary, the absence o f matter!

The native art o f dancing is a'continuation o f pure rhythm and

graceful movements and positions being, especially in Java, solely

an artexpression; native dancing is certainly not intended' 'as a

means to promote intercourse between the sexes. The dancing rules,

handed down from tradition, exclude all obscenities a s sacrilege.

The well-known art o f batik can not be dealt with fully here.

I only call attention to the rhythmic and harmonic drawing,

and the intentional departure from and aim to the supernatural

which is resorted to. Unfortunately some modern industrial influences

have done irrepairable damage to this ancient art o f

drawing which is founded on tradition.

Remarkable is the sensibility for art expressed in woodcutting

more specially in that worked with or without colours on

bamboo-cylinders. Beadwork is done in Bornéo; with regard