•' interior membranacea, albida, bilineata; c

dorso canaliculate, margine insigniter in

ad apiceni ciliato-scabra.

Squamuue duæ; membranaceæ, albæ, oblongæ, trifidæ,.

segmentas inæqualibus, acutis.

Stamina tria ; Antheræ luteæ.

G ermen ovato-globosum ; Stigmata plumosa.

before the apex, or often produced into a

lined.

short

scabroi

r membranaceous, white, two.

veless, canaliculated on the back tli

markably involute, a t the apex cilia™

Squamules two, membranaceous, white, oblong&, ttr| ifid,

with the segments unequal, acute.jfev ,

Stamens three; Anthers yellow. ■

Ge rm en ovato-globose; Stigmas plumose, fig . g.

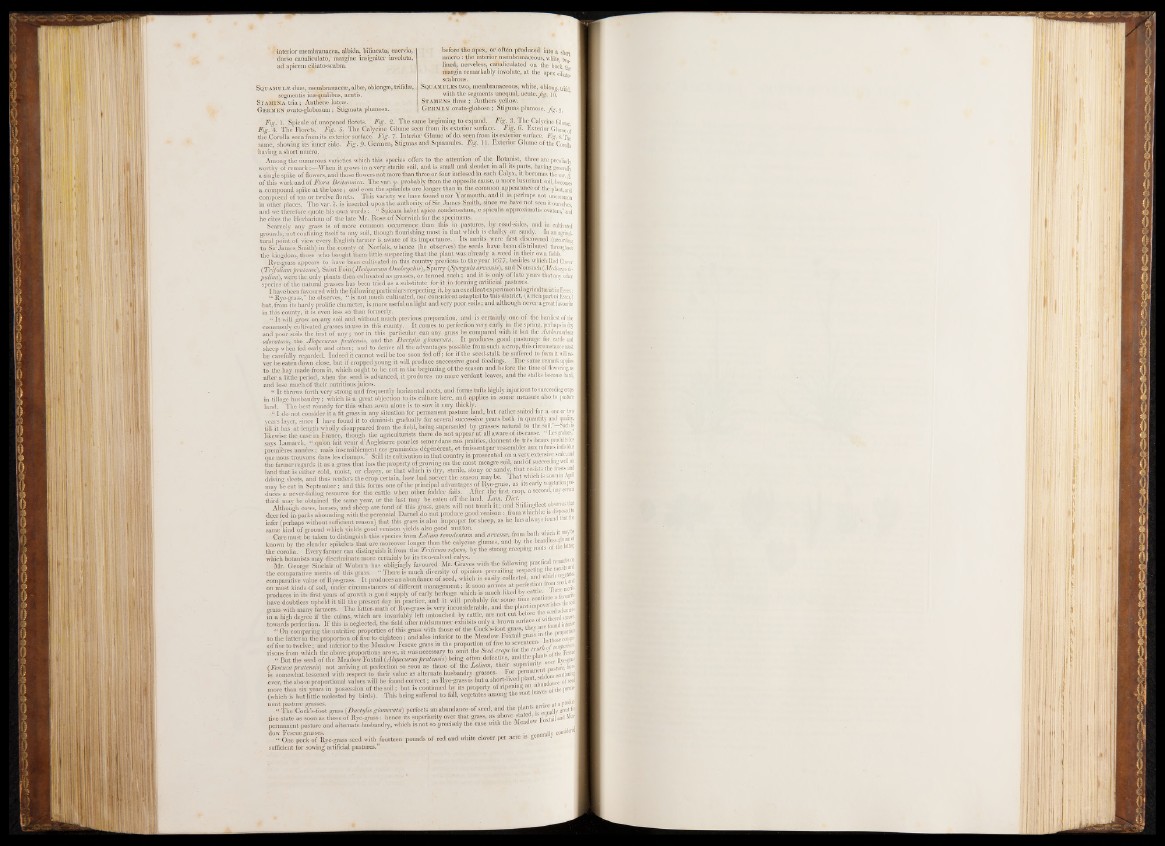

Fig. 1. Spicule of unopeued florets. Fig. 2. The same beginning to expand. Fig. 3. The Calycine Glume

Fig. 4. The Florets.' Fig. 5. The Calycine Glume seen from its exterior surface. Fig. 6. Exterior Glume of

the Corolla seen from its exterior Surface. Fig. 7. Interior Glume of do. seen from its exterior-surface, 8. The

same, showing its inner side. Fig. 9- Germen, Stigmas and Squamules. Fig. 11. Exterior Glume of the Corolla

having a short mucro.

Among the numerous varieties which this species offers to the attention of the Botanist, three are peculiarly

irthy of rem a rk—When it grows in a very sterile soil, and is small and slender in all its parts, having generally

a single spike of flowers, and those flowers not more than three or four inclosed in each Calyx, it becomes hie var™

of tins work and of Flora Britannica. The var. y . probably from the opposite cause, a more luxuriant soil, becomes

a compound spike at the base; and even the spikelets are longer than in the common, appearance of the plant, and

composed of ten or twelve florets. This variety we have found near Yarmouth, aud it ,is perhaps not uncommon

in other places. The var. §. is inserted upon the authority of Sir Jamqs Spri t]),, since we have not seen its ourselves,

and we therefore quote his own words: “ Spicam habet apic? .condensatam,:e spiculis approximatis ovatam/'and

he cites the Herbarium of the late Mr. Rose of Norwich for the specimens.

Scarcely any g rass is of more common occurrence than th is in pastures, by road-sides, and in cultivated

grounds, not confining itself to any soil, though flourishing most in that- which is chalky -or sandy. In an lgncultural

point of view every English’farmer is aware of its importance. Its merits were .first discovered (according I

to Sir James Smith) in the county, of Norfolk, whence (he observes) the seeds have been distributed throughout I

the kingdom, those who bought them little suspecting that the plant was already a weed in-their own fields.

Rye-°rass appears to have been cultivated in this country previous to the year 1677, besides which Red Clover I

(TrifoUum pratense), Saint Foin (Heilysarum Onobrychis),.Spurry {Spergula aiyensis), and Nonsuch (Mcdicago lu- I

puli/ta), were the only plants then cultivated as grasses, or termed such ; and it is . only of late years that any other I

species of the natural grasses has been tried as a substitute for it in forming artificial pastures.

I have been favoured with the following particulars respecting it, by anexcellent ex peri mental agriculturist in Essex : I

“ Rye-grass,” he observes, “ is not much cultivated, nor considered adapted to this district,-(a rich part of Essex,) I

but, from its hardy prolific character, is more useful on light and very poor, soils ; and although never à great favourite I

in this county, it is even less so than formerly.

“ It will grow on any soil and without much previous preparation, and is certainly one of the hardiest of the I

commonly cultivated glasses in use in this county. It comes to perfection very early in the spring, perhaps in dry I

and poor soils the first of any ; nor in this particular can any grass be compared with it but the Anthoxantkm I

odorat um, the Alopecurus pratensis, and the Dactylis glomerata. It produces good pasturage for cattle and I

sheep when fed early and often ; and to derive all the advantages possible from such acrop, this circumstance must I

be carefully regarded. Indeed it cannot well be too soon fed off; for if the seed-stalk be suffered to form it will ne- I

ver be eaten down close, but if cropped young it will produce successive good feedings. The same remark applies I

to the hay made from it, which ought to be cut in the beginning of the season and .before the time of flowering, as I

after a little period, when the seed is advanced, it produces no moj-e verdant leaves, and the stalks become hard, I

and lose much of their nutritious juices. ' . .

“ It throws forth very strong and frequently horizontal roots, and forms tufts highly injurious to succeeding crops I

in tillage husbandry; which is a great objection to its culture here, and applies in some measure also to pasture I

land. The best remedy for-this when sown alone is to sow it very thickly. : -i _ ■

“ I do not consider it a fit grass in any situation for permanent pasture.land, but rather suited for à,one or two I

years layer, since I have found it to diminish gradually for several successive years both in. quantity and quality, I

till it has at length wholly disappeared from the field, being superseded by grasses natural to the soil.”—Such is I

likewise the casein France, though the agriculturists there do not appear at all aware of its cause. “ Les graines, I

says Lamarck, “ qu’on fait venir d’Angleterre pour les semer dans nos prairies, donnent de très beaux produits les I

premières années; mais insensiblement ces graminées dégénèrent, et finissent par ressembleraux mômes individus I

nue nous trouvons dans les champs.” Still its cultivation in that country is prosecuted on a very extensive scale, and I

the farmer regards it as a grass that has the property of growing on the most meagre soil, and of succeeding well on I

land that is either cold,, moist, or clayey, or that which is dry, sterile, stony or sandy, that resists tlie Irosts and 1

driving sleets, and thus renders the crop certain, how bad soever the season maybe. That which is sown in p ■

may be cut in September ; and this forms one of the principal advantages of Rye-gràss, as its early vegetation pr ■

duces a- never-failing resource for the cattle when other fodder fails. After the first crop, a second, nay eien ■

third mav be obtained the same year, or the last may be eaten off the land. Lam. Diet. , .

Although cows, horses, and sheep are fond of this grass, goats will not touch it; and Stillmgfleet obseivfoOT■

deer fed in parks abounding with the perennial Darnel do not produce good venison : from winch he is u

infer (perhaps without sufficient reason) that this grass is also improper for sheep, as he has always tounci 1

same kind of ground which yields good venison yields also good mutton. . , . u I

Care must be taken to distinguish this species from Lolium temulentum and arcense,.froim both wn cn it ) ■

known by the slender spikelets that are moreover longer than the calycine glumes, and by the beaidl^ „ . 1

the corolla. Every farmer can distinguish it from the Tritieum rèpens, by the strong creeping roots ot t

which botanists may discriminate more certainly by its two-valved calyx, . . remarks on I

Mr. George Sinclair of Woburn has obligingly favoured Mr. Graves with the following p r a c t i c , j I

the comparative merits of tins grass. “ There is much diversity o f opinion prevailing r e s p e c t .«

comparative value of Rye-grass. It produces an abundance of seed, which is easily collected, and ' an(| ;

on most kinds of soil, under circumstances ' of different management; it soon arrives atperlecmon •

produces in its first years of growth a good supply of early herbage which is much liked by ca^ • & fovouritc|

have doubtless upheld it till the present day in practice, and it will probably tor some time thesoill

grass with many farmers. The lattèr-math of Rye-grass is very inconsiderable, and the plantimpove ^ ■

in a high degree if the culms, which are invariably left untouched by cattle, are not cut be nfw;ti)ered straws. I

towards perfection. I f this is neglected, the field after midsummer exhibits only a brown surface oi infcrior 1

“.On comparing the nutritive properties of this grass with those of the Cock s-foot grass, th y proportion

to the latter in the proportion of five to eighteen ; and also inferior to the Meadow 1'oxtail g1^ T.n those comp8-1

of five to twelve ; and inferior to the Meadow Fescue grass in the proportion of five to sevente • . gi.^ ,1

risons from which the above proportions arose, it was necessary to omit the Seed crops tor the m am m ^ Fescue

“ Rut the seed of the Meadow Foxtail {Alopecurus pratensis) being often defective, and the p jj,ye-gws5

(Festucapratensis) not arriving at perfection so soon a- t those a p of the Lolium,T*ih,m thnr.their | superiority^j g g g j -y:

j • l

-is somewhat lessened with respect to their value as altt

late husl

ever, the above proportional values will be found correct

asRye-j

.more than six years in possession r— |M of the soil;.

but is continued by its property of ripening

- (which is but little molested ■ by birds). - This ^ v ’being ' - - suffered • « - - a .* to . is-fall.

M- vegetates among the root leaves s» ■

nent pasture grasses. . , , nl.r;ve at a Pr0(¥ ’

“ The Cock’s-foot grass {Dactylis glomerata) perfects an abundance of seed, and the plants u great lor

fuivvee ssutaiutes aass ssoooonn aass tmhuossee uoif iRv^yec--ggiraassss :: ihieeiniucee iutss ssuuppeeriiiOoriiutyy ouvvecri tuhaati ggriaassss,, aass aaubvo*vve. stated,, r-J ^ ]\fea-;

permanent pasture and alternate husbandry, which is not so precisely the case with the M

dow Fescue grasses. : . • . • . . . • generally

considered!

“ One peck of Rye-grass seed with fourteen pounds of red and white clover per acre is 0

sufficient for sowing^artificial pastures.”