ill

The taste of the majority of the Basidiomycetes when raw is

watery-insipid; many are practically tasteless or mild. Some when

uncooked have a pleasant nutty flavour, as Psalliota campestris

(mushroom) and Lepiota procera. Several are bitter, as Boletus

felleus; others are bitter-nauseous, as Hypholo^na fasciculare, and

many species of Lactarius and Russula are very acrid or bitter

acrid.

The odours are most diverse. Clitocybe fragrans is very sweet

and recalls Melilot, as does also ILydnum graveolens; C. odora is

fragrant of Woodruff or Vernal Grass; Trametes suaveolens, T.

odora, Lactarius glyciosmus and Clavaria stricta are also very sweet-

scented. One variety of Cantharellus cibarius smells strongly of

apricots, and Clitocybe geotropa is almond-scented. Many smell

strongly of onions or garlic, the best known examples being

different species of Marasmius. Fetid and disgusting odours are

common ; a familiar instance is that of Lthyphallus impudicus. The

odours possibly serve some purpose at present unknown. The

carrion-scented species attract swarms of carrion-feeding insects

which greedily devour the highly fetid, soft, sporiferous material

of the Phalloidacca.

The exudation of fluid, the so-called milk, when the stem is

broken, is a remarkable character of some species. Mycena galopus

and M. lactea contain a white, M. crocata and M. chelidonia a yellow,

M. hceuiatopus a dark purple-red, and M. sanguinolenta a red juice •

Lactarius deliciosus exudes an orange-coloured and L. sanguifluus

a deep blood-red juice which, on exposure to the air, quickly

becomes green. The milk of L. chrysorrheus and L. theiogalus is

sulphur-yellow,_ that_ of Z. acris is at first white, then reddish. The

milk of Z. uvidus is white and quickly changes to violet • that of

L scrobiculatus is first white, then sulphur; that o i L. fuliginosus

white, then saiFron. T. he stem of Marasjiims varicosus is filled with

dark blood-red juice, which flows when the stem is bruised or

broken.

Some species of Agaricacece, as LLypholoma lacrymabuiidum and

H. velutinum, have “ weeping gills” ; in mature examples drops of

fluid may be seen sprinkled all over the surface of the gills which

when examined, under the microscope, are seen to be charged with

spores and cystidia. The hymenium of the dry rot fungus, Merulius

laciymans, IS usually covered with globules of exuded moisture;

Polyporus dryadeus is often seen in the same condition.

The Basidiomycetes as a rule do not exhibit brilliant colouring

but there are remarkable exceptions, the most striking being scarlet

and crimson, as m Amanita muscaria. Yellow, orange, blue purple

and whne also occur, also rarely green and black, but the majority

are pallid, watery-brown, brown, greyish or buff. The brown and

buff colours of Agarics often cause the fungi to be overlooked when

growing amongst dead leaves.

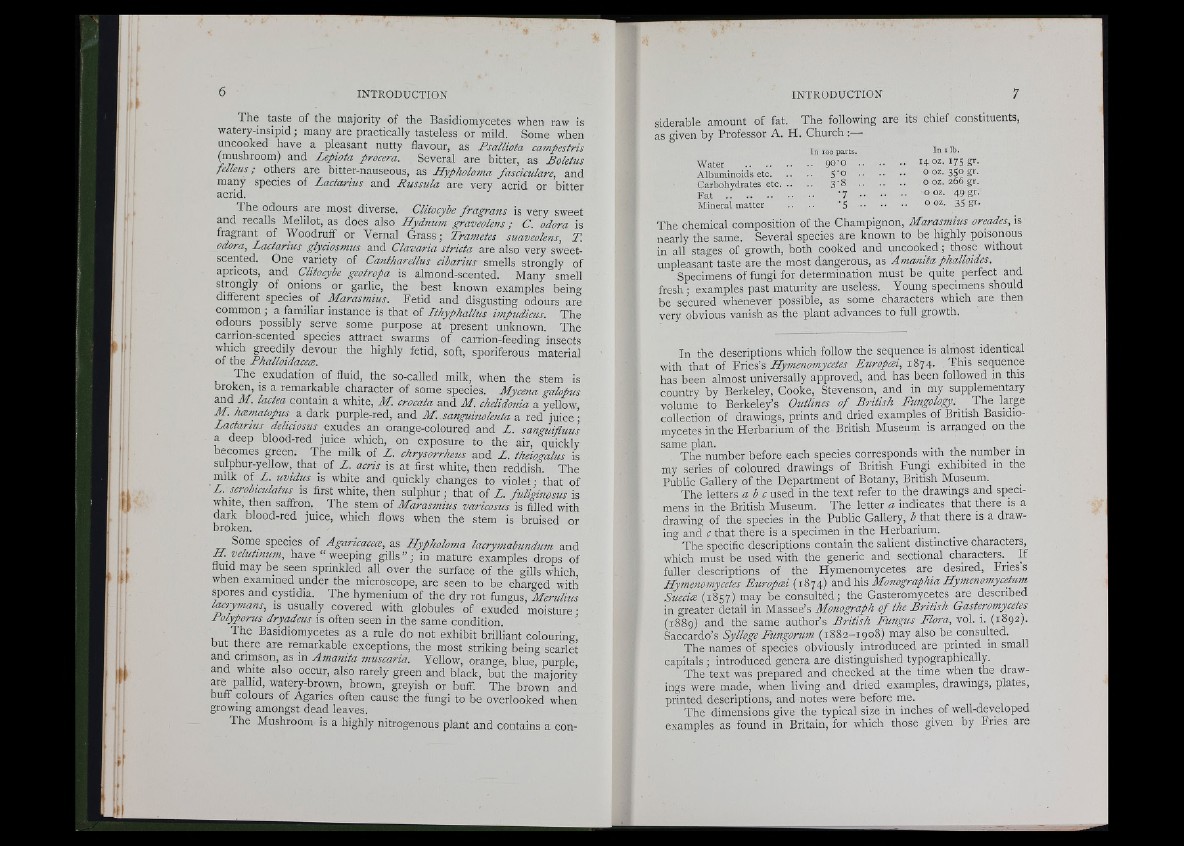

The Mushroom is a highly nitrogenous plant and contains a considerable

amount of fat. The following are its chief constituents,

as given by Professor A. H. Church:

In loo parts. In t

Water ........................... 9 ° '° 14 oz. 175 gr.

Albuminoids etc.................... 5'o o oz. 350 gr.

Carbohydrates etc............. 3 '8 o oz. 266 gr.

Fat ........................................ -7 ooz. 4 9 .?r•

Mineral matter .. .. "5 o oz. 35 gr.

The chemical composition of the Champignon, Marasmius oreades, is

nearly the same. Several species are known to be highly poisonous

in all stages of growth, both cooked and uncooked; those without

unpleasant taste are the most dangerous, as Amanita phalloides.

Specimens of fungi for determination must be quite perfect and

fresh; examples past maturity are useless. Young specimens should

be secured whenever possible, as some characters which are then

very obvious vanish as the plant advances to full growth.

In the descriptions which follow the sequence is almost identical

with that of Fries’s LLymenomycetes Europcei, 1874. Ihis sequence

has been almost universally approved, and has been followed in this

country by Berkeley, Cooke, Stevenson, and in my supplementary

volume to Berkeley’s Outlines of British Fungology.

collection of drawings, prints and dried examples of British Basidiomycetes

in the Herbarium of the British Museum is arranged on the

same plan. , • , , t, ■

The number before each species corresponds with the number in

my series of coloured drawings of British Fungi exhibited in the

Public Gallery of the Department of Botany, British Museum.

The letters a b c used in the text refer to the drawings and specimens

in the British Museum. The letter a indicates that there is a

drawing of the species in the Public Gallery, ¿ that there is a drawing

and c that there is a specimen in the Herbariuin.

The specific descriptions contain the salient distinctive characters,

which must be used with the generic and sectional characters. If

fuller descriptions of the Hymenomycetes are desired, Fries s

Hymenoinycetes Europmi ( 1874) and his Monographia Hymenomycetum

SuecicE ( 1857) may be consulted; the Gasteromycetes are described

in greater detail in Massee’s Monograph of the British Gasteromycetes

( 1889) and the same author’s British Ftmgus Flora, vol. i. (1892).

Saccardo’s Sylloge Fungorum (1882- 1908) may also be consulted.

The names of species obviously introduced are printed in small

capitals; introduced genera are distinguished typographically.

The text was prepared and checked at the time when the drawings

were made, when living and dried examples, drawings, plates,

printed descriptions, and notes were before me.

The dimensions give the typical size in inches of well-developed

examples as found in Britain, for which those given by Fries are