The larger Fungi not described in this work are a few of the

Ascomycetes, including the Morel and its allies, the true ascus-

bearing Truffles and a limited number of Cup-fungi.

The microscope is unnecessary for the determination of the

greater number of the Basidiomycetes; nearly all are large and can

be satisfactorily examined by the unaided eye or with the assistance

of a hand-lens. A few forms found under Family iv Thekphoracece,

as Solenia and Cyphella, superficially resemble certain of the Ascomycetes,

as Peziza; but with a little experience even obscure forms

may be easily determined with the aid of a

simple lens. In some genera of the Thekphoracece

a microscopic examination of the hymenium is

sometimes desirable.

The Basidiomycetes are highly, plastic and

variable. No one species is constant in all its

characters, and a single example seldom wholly

accords with any other single example of the

same species. Examples which appear to be

intermediate between allied, and sometimes

between not allied, species are frequently met

with. About one species in ten is perhaps fairly

well and distinctly marked, but all species will

at times present aberrant characters. Any one

character is liable to fail; in the determination

of species, therefore, all the characters must be

studied together.

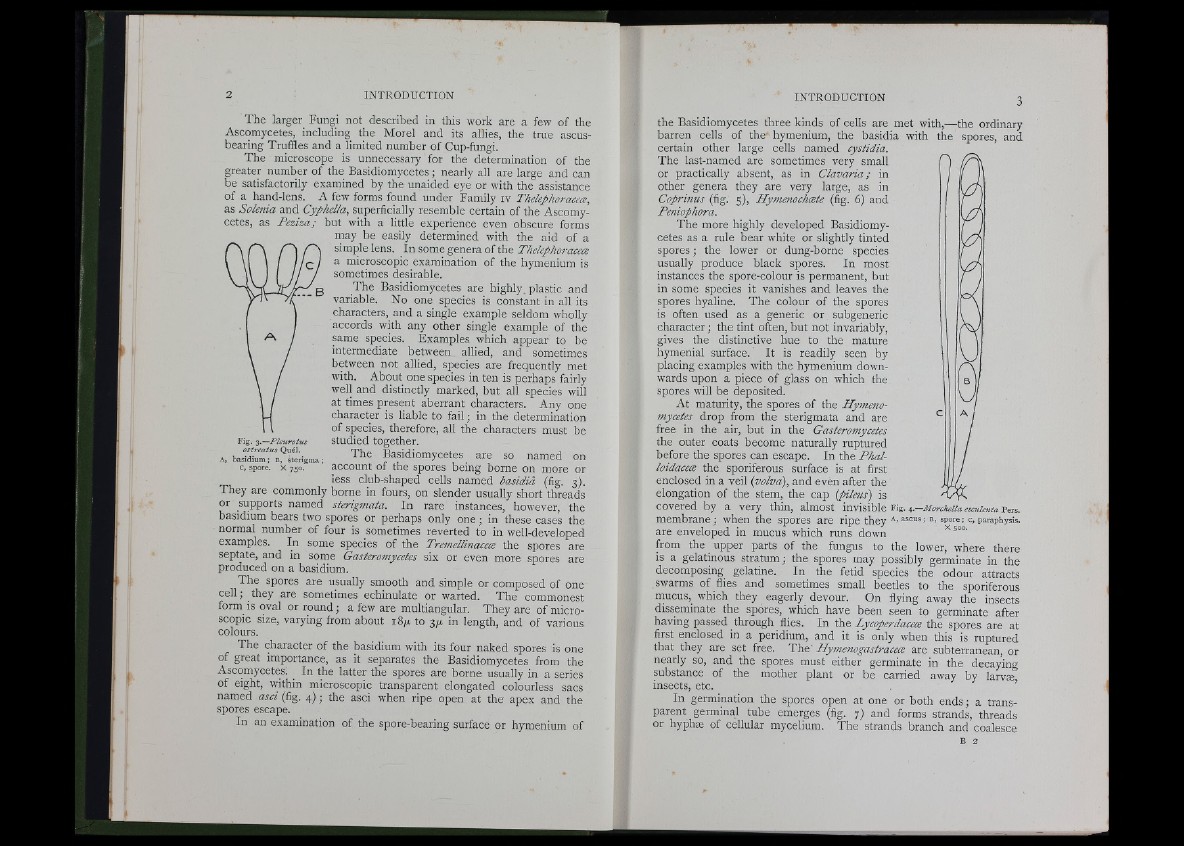

The Basidiomycetes are so named on

account of the spores being borne on more or

iess club-shaped cells named basidia (fig. 3).

Fig. 2 —Pteurotus

ostreains Quél.

, basidium ; b, sterigma ;

c, spore. X 750.

They are commonly borne in fours, on slender usually short threads

or supports named sterigmata. In rare instances, however, the

basidium bears two spores or perhaps only on e ; in these cases the

normal number of four is sometimes reverted to in well-developed

examples. In some species of the Tremellinacece the spores are

septate, and in some Gasteromycetes six or even more spores are

produced on a basidium.

The spores are usually smooth and simple or composed of one

cell; they are sometimes echinulate or warted. The commonest

form^ is oval or round; a few are multiangular. They are of microscopic

size, varying from about i 8/r to 3/r in length, and of various

colours.

The character of the basidium with its four naked spores is one

of great importance, as it separates the Basidiomycetes from the

Ascomycetes. In the latter the spores are borne usually in a series

of eight, within microscopic transparent elongated colourless sacs

named asa (fig. 4); the asci when ripe open at the apex and the

spores escape.

In an examination of the spore-bearing surface or hymenium of

the Basidiomycetes three kinds of cells are met with,— the ordinary

barren cells of the hymenium, the basidia with the spores, and

certain other large cells named cystidia.

The last-named are sometimes very small

or practically absent, as in C¿avaria ; in

other genera they are very large, as in

Coprinus (fig. 5), Hymenochoete (fig. 6) and

Penioptiora.

The more highly developed Basidiomycetes

as a rule bear white or slightly tinted

spores ; the lower or dung-borne species

usually produce black spores. In most

instances the spore-colour is permanent, but

in some species it vanishes and leaves the

spores hyaline. The colour of the spores

is often used as a generic or subgeneric

character ; the tint often, but not invariably,

gives the distinctive hue to the mature

hymenial surface. It is readily seen by

placing examples with the hymenium downwards

upon a piece of glass on which the

spores will be deposited.

At maturity, the spores of the Hymeno-

mycetes drop from the sterigmata and are

free in the air, but in the Gasteromycetes

the outer coats become naturally ruptured

before the spores can escape. In the Phal-

loidaceæ the sporiferous surface is at first

enclosed in a veil (volva), and even after the

elongation of the stem, the cap (pileus) is

covered by a very thin, almost invisible Fig. ¡..—Morckeiia escuimta Pers.

membrane ; when the spores are ripe they paiaphysis.

are enveloped in mucus which runs down

from the upper parts of the fungus to the lower, where there

is a gelatinous stratum; the spores may possibly germinate in the

decomposing gelatine. In the fetid species the odour attracts

swarms of fiies and sometimes small beetles to the sporiferous

mucus,^ which they eagerly devour. On flying away the insects

disseminate the spores, which have been seen to germinate after

having passed through flies. In the Lycoperdacece the spores are at

first enclosed in a peridium, and it is only when this is ruptured

that they are set free. Hymenogastraceæ are subterranean, or

nearly so, and the spores must either germinate in the decaying

substance of the mother plant or be carried away by larvæ

insects, etc. ’

In germination the spores open at one or both ends ; a transparent

germinal tube emerges (fig. 7) and forms strands, threads

or hyphæ of cellular mycelium. The strands branch and coalesce

B 2