The Norwegian non-eeclesiastical architecture has partly employed

stone, partly wood for its buildings. Masonry was used chiefly

for bishops’ palaces and convents and for royal castles, while only

wood was used for houses in the country, and generally in the

towns also. The only monastery that has heen to some extent

preserved is that of St. Laurence at Utstein, north of Stavanger.

The design here, as well as that evident in ruins elsewhere, is on

the ordinary European plan.

Interesting and fairly well preserved portions of the archbishop’s

palace in Trondhjem, and some remains of the bishop’s

palaces in Stavanger, Oslo and Hamar still exist.

Among remains of royal castles, some from the 13th century

must be especially mentioned.

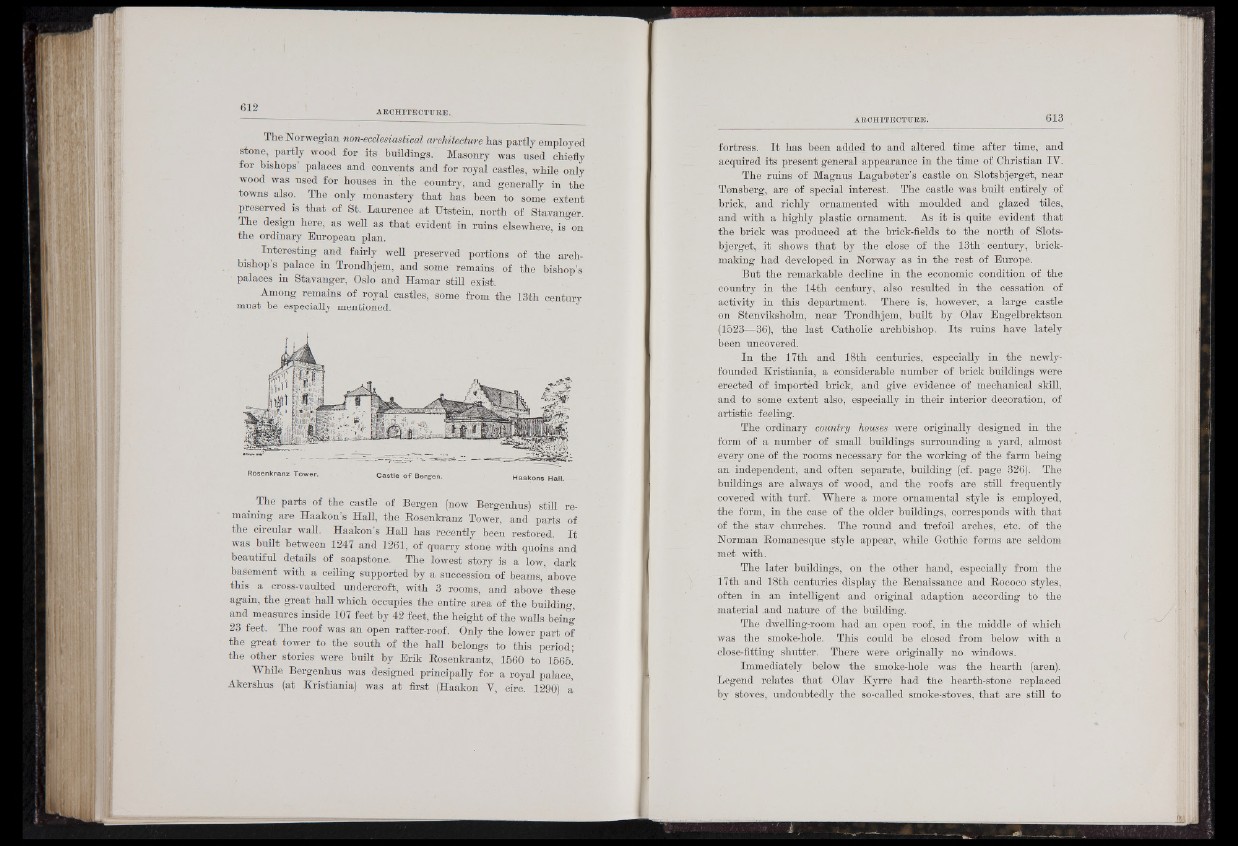

Rosenkranz Tower. Castle o f Bergen. Haakons Hall.

The parts of the castle of Bergen (now Bergenhus) still remaining

are Haakon’s Hall, the Bosenkranz Tower, and parts of

the circular wall. Haakon’s Hall has recently been restored. I t

was built between 1247 and 1261, of quarry stone with quoins and

beautiful details of soapstone. The lowest story is a low, dark

basement with a ceiling supported by a succession of beams, above

this a cross-vaulted undercroft, with 3 rooms, and above these

again, the great hall which occupies, the entire area of the building,

and measures inside 107 feet by 42 feet, the height of the walls being

23 feet. The roof was an open rafter-roof. Only the lower part of

the great tower to the south of the hall belongs to this period;

the other stories were built by Erik Bosenkrantz, 1560 to 1565.'

While Bergenhus was designed principally for a royal palace,

Akershus (at Kristiania) was at first (Haakon Y, circ. 1290) a

fortress. I t has been added to and altered time after time, and

acquired its present general appearance in the time of Christian IY.

The ruins of Magnus Lagaboter’s castle on Slotsbjerget, near

Tonsberg, are of special interest. The castle was built entirely of

brick, and richly ornamented with moulded and glazed tiles,

and with a highly plastic ornament. As it is quite evident that

the brick was produced at the brick-fields to the north of Slotsbjerget,

it shows that by the close of the 13th century, brick-

making had developed in Norway as in the rest of Europe.

But the remarkable decline in the economic condition of the

country in the 14th century, also resulted in the cessation of

activity in this department. There is, however, a large castle

on Stenviksholm, near Trondhjem, built by Olav Engelbrektson

(1.523- 36), the last Catholic archbishop. Its ruins have lately

been uncovered.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, especially in the newly-

founded Kristiania, a considerable number of brick buildings were

erected of imported brick, and give evidence of mechanical skill,

and to some extent also, especially in their interior decoration, of

artistic feeling.

The ordinary country houses were originally designed in the

form of a number of small buildings surrounding a yard, almost

every one of the rooms necessary for the working of the farm being

an independent, and often separate, building (cf. page 326). The

buildings are always of wood, and the roofs are still frequently

covered with turf. Where a more ornamental style is employed,

the form, in the case of the older buildings, corresponds with that

of the stav churches. The round and trefoil arches, etc. of the

Norman Bomanesque style appear, while Gothic forms are seldom

met with.

The later buildings, on the other hand, especially from the

17th and 18th centuries display the Benaissance and Bococo styles,

often in an intelligent and original adaption according to the

material and nature of the building.

The dwelling-room had an open roof, in the middle of which

was the smoke-hole. This could be closed from below with a

close-fitting shutter. There were originally no windows.

Immediately below the smoke-hole was the hearth (aren).

Legend relates that Olav Kyrre had the hearth-stone replaced

by stoves, undoubtedly the so-called smoke-stoves, that are still to