Worlc in silver forms the other side of our national art-

handicraft. I t is more especially the very simple, but effective

filigree work that has been done by our peasants brooches with

low-relief ornaments in the form of leaves, or saucers hanging by

fine chains from the body of the brooch, and glittering with every

movement; double buckles or heart-shaped clasps, intended for

fastening the bodice in front; buttons with fine chains; rings, and

belts composed of silver plates embossed with ornaments of leaves,

etc. The numerous silver-gilt bridal crowns, on the other hand,

have been, to some extent at least, made in the towns. Bergen,

in particular, early possessed a highly-developed goldsmith’s art.

Even in pur century magnificent brooches, etc. are made in diffe-

Norwegian Buckle.

rent parts of the country, especially in Telemarken; but of late most

silver work in national forms is done in the towns.

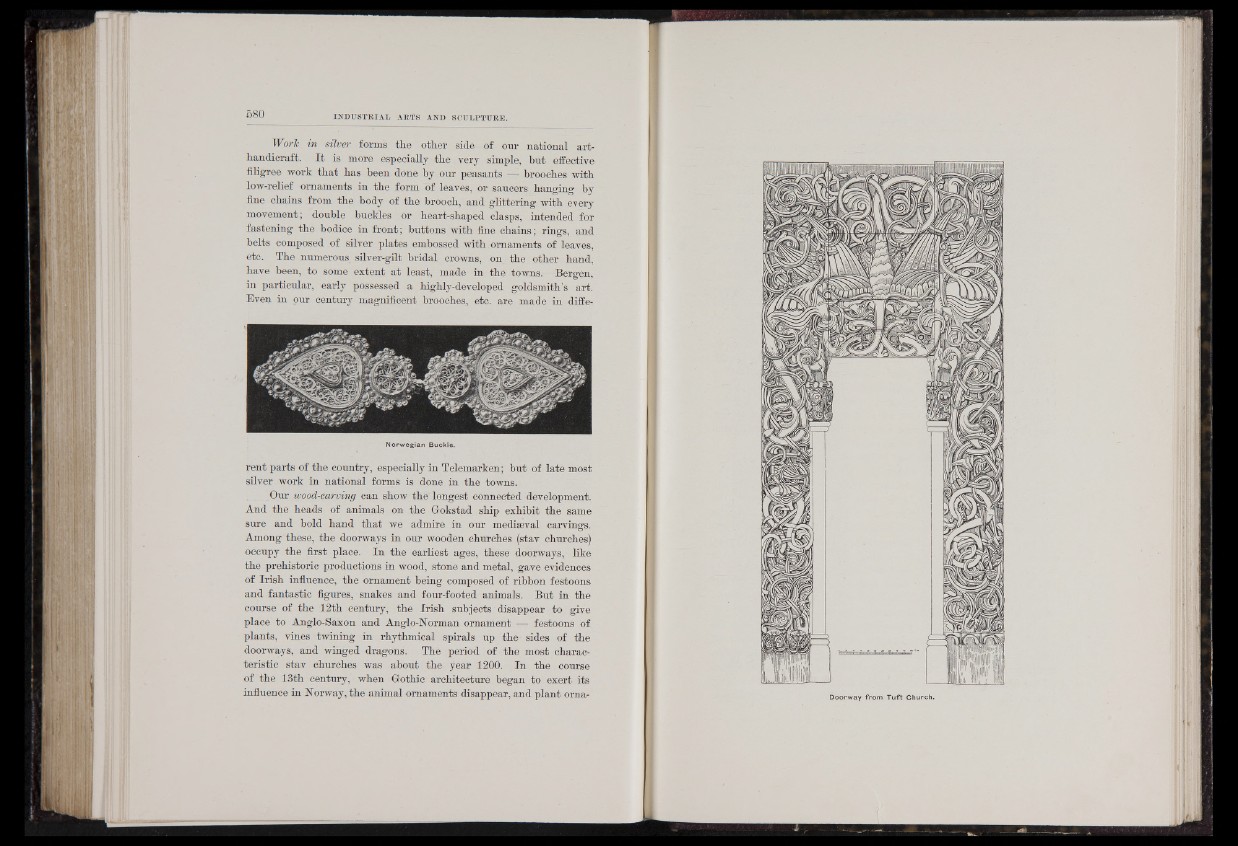

Our wood-carving can show the longest connected development.

And the heads of animals on the Gokstad ship exhibit the same

sure and bold hand that we admire in our mediseval carvings.

Among these, the doorways in our wooden churches (stav churches)

occupy the first place. In the earliest ages, these doorways, like

the prehistoric productions in wood, stone and metal, gave evidences

of Irish influence, the ornament being composed of ribbon festoons

and fantastic figures, snakes and four-footed animals. But in the

course of the 12th century, the Irish subjects disappear to give

place to Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman ornament — festoons of

plants, vines twining in rhythmical spirals up the sides of the

doorways, and winged dragons. The period of the most characteristic

stav churches was about the year 1200. In the course

of the 13th century, when Gothic architecture began to exert its

influence in Norway, the animal ornaments disappear, and plant ornaDoorway

from Tuft Church.