The series commences with H a l v o r E a n d e n ’s (abont 1650) two

representations of Norwegian peasants, and several drinking-mugs

adorned with mythological and allegorical reliefs, all rather ronghly

executed, and possibly to some extent copied from Netherland

prints. M a g n u s E l i s e n B e r g (1666—1739), a carver in ivory,

stands far above his contemporaries in this species of art, with

his excellent reliefs, representing scenes from sacred history, mythology

and allegory (Rosenborg Palace, the historical art museum

m Vienna, and the royal collections in England). He stands at the

summit of the art of his time, and together with his age, has a

leaning towards Rococo. His goblets with ivory reliefs are among

the most beautiful ivory wprk of all ages. J a k o b K l u k s t a d (d. 1773)

Modern Wood-carving.

seems to have been more influenced by the old national wood-

carving art. He carved the pulpit and altar-piece in Lesje Church

with rich and beautiful «kralleskurd». In Valdres, E t s t e i n G u t -

t o r m s e n E j o r r e n (circ. 1800) carved the remarkable altar-piece in

Hegge Church, representing the Crucifixion, in numerous detached

figures. The series of wood-carvers is continued down to our own

time with men such as O l e M o e n e from Opdal, L a r s K i n s e r v i k

from Hardanger, L i n s 0 from the Dovre district, and H y l l a n d from

Telemarken, who have all confined themselves to the carving of

ornament in the traditional style, in which they have attained a

high degree of perfection.

I t is this same inborn, traditionally-confirmed genius for the

artistic treatment of wood that has also been the starting-point for

the Norwegian sculptural art of our day. In this has lain both

its strength and its limitation, its strength, because this certainty

in the. ornamental treatment of wood forms a good, firm starting-

point for further artistic training; its limitation, because it is a

long time before the artists trained upon this basis can entirely

shake off tradition, and turn from the ornamental which is their

strong point, to the free representation of the human figure, which

is the chief domain of sculpture. All our earlier, peasant-born

sculptors have been far more talented as ornament-carvers than as

sculptors, and have therefore often had a hard fight to assert themselves

in the foreign domain, and in strange conditions.

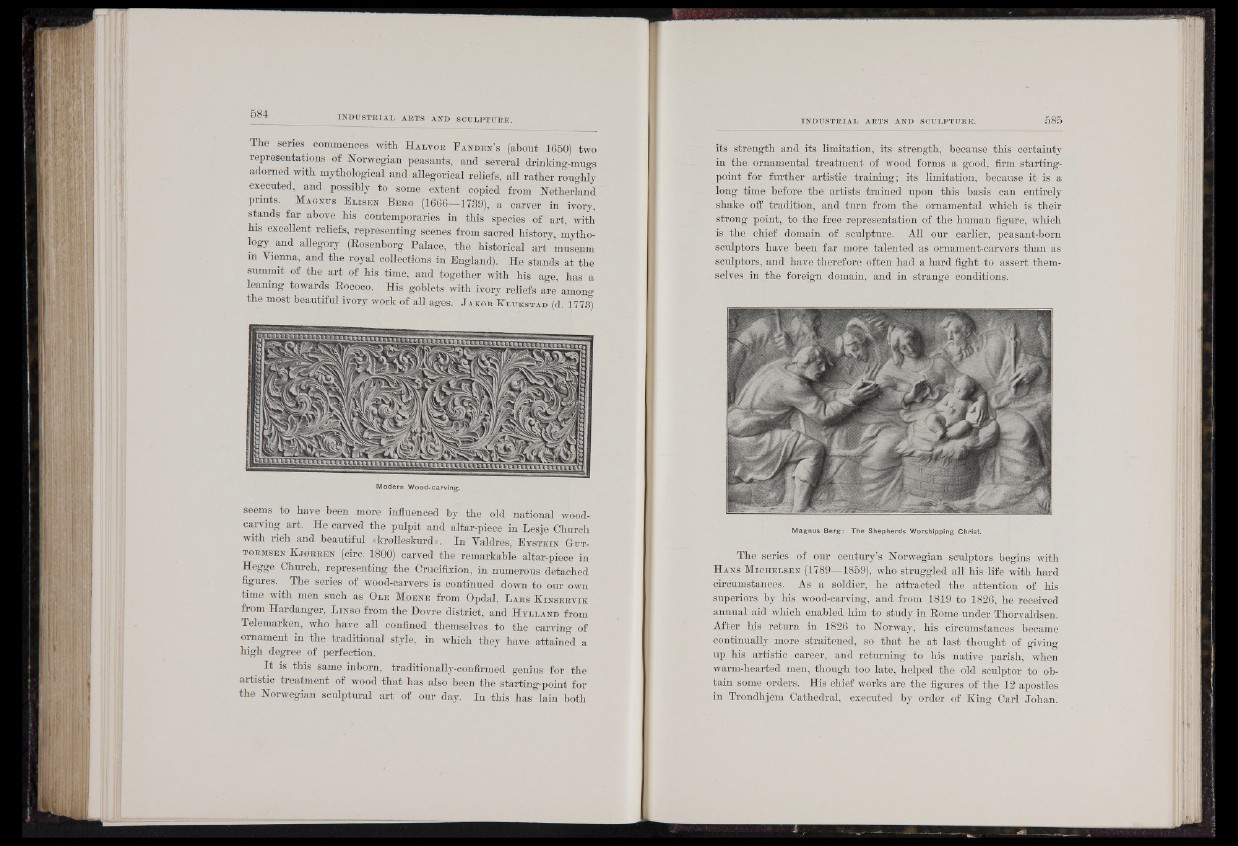

Magnus Berg: The Shepherds Worshipping Christ.

The series of our century’s Norwegian sculptors begins with

H a n s M i c h e l s e n (1789—1859), who struggled all his life with hard

circumstances. As a soldier, he attracted the attention of his

superiors by his wood-carving, and from 1819 to 1826, he received

annual aid which enabled him to study in Rome under Thorvaldsen.

After his return in 1826 to Norway, his circumstances became

continually more straitened, so that he at last thought of giving

up his artistic career, and returning to his native parish, when

warm-hearted men, though too late, helped the old sculptor to obtain

some orders. His chief works are the figures of the 12 apostles

in Trondhjem Cathedral, executed by order of TTiug Carl Johan.