Here, at the establishment of the archbishopric in 1152,

stood Olav Kyrre’s Christ Church, which was not calculated to

satisfy the special requirements of a metropolitan church, and

therefore underwent thorough alterations.

Archbishop Eystein (1160—1188) was especially active in this

work. In 1180, for political reasons, he was obliged to flee to

England. Just at that time, the choir of Canterbury Cathedral

was being rebuilt by William of Sens and William the Englishman,

with the pointed arch and an exceedingly beautiful expression

of form, which was the introduction of the Early English style.

The east end of the cathedral terminates in the horse-shoe-formed

St. Thomas s corona, which was probably the model for the octagon

in Trondhjem.

Evidently with fresh impressions from England, Eystein determined,

on his return in 1183, to rebuild the choir of Christ Church.

Only the lower part of it, and of the octagon at the east end

with its aisle and chapels, show Eystein’s transition style. The upper

parts are fully developed early Gothic, and the arch in front of

the octagon has traceries characteristic of the 14th century. The

roof of the aisleless transept is open, while the choir was covered

with richly ornamented cross-vaulting. The chapter-house, north

of the choir, must have been erected before 1179. The material

used throughout the church is soapstone, the beautiful green

shade in its colour being brought out by the employment everywhere

of white marble pillars.

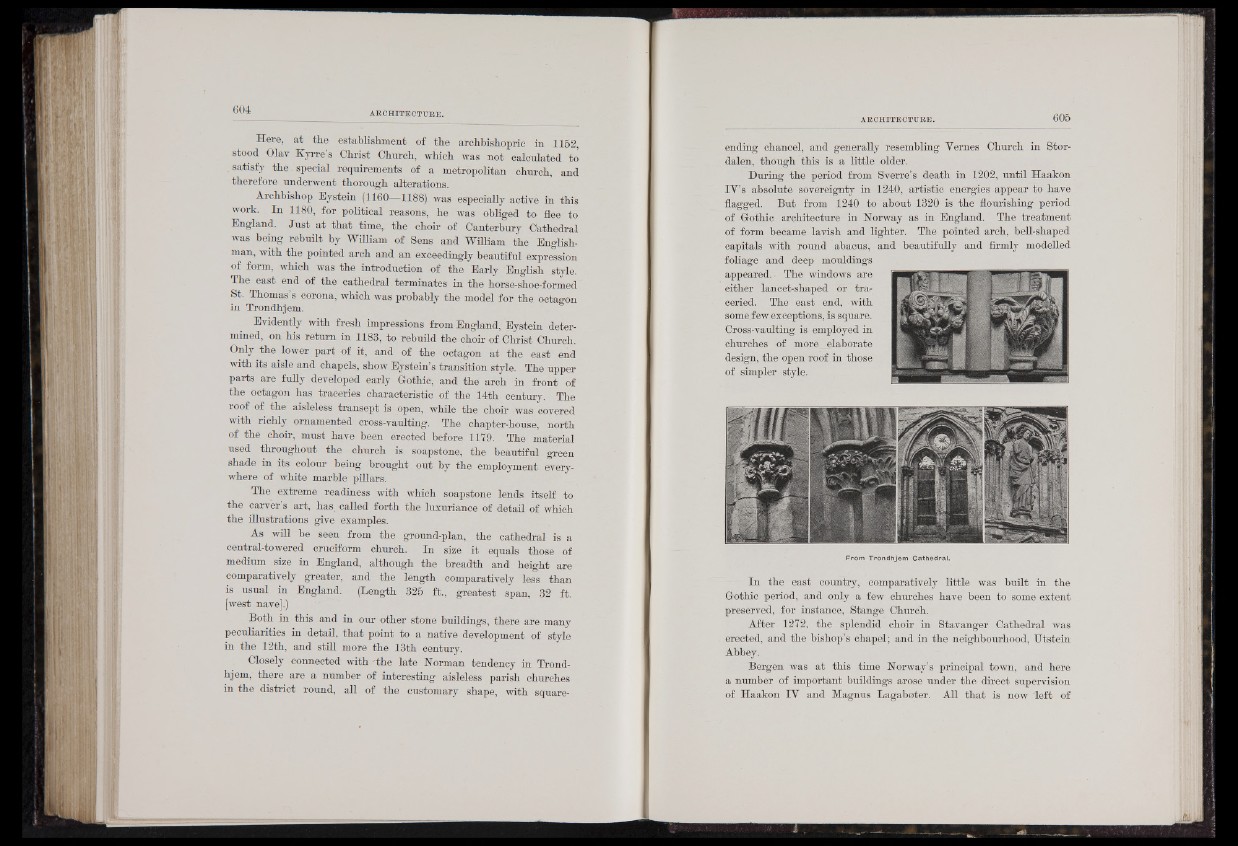

The extreme readiness with which soapstone lends itself to

the carver s art, has called forth the luxuriance of detail of which

the illustrations give examples.

As will be seen from the ground-plan, the cathedral is a

central-towered cruciform church. In size it equals those of

medium size in England, although the breadth and height are

comparatively greater, and the length comparatively less than

is usual in England. (Length 325 ft., greatest span, 32 ft.

[west nave].)

Both in this and in our other stone buildings, there are many

peculiarities in detail, that point to a native development of style

in the 12th, and still more the 13th century.

Closely connected with the late Norman tendency in Trond-

hjeni. there are a number of interesting aisleless parish churches

in the district round, all of the customary shape, with squareending

chancel, and generally resembling Yemes Church in Ster-

dalen, though this is a little older.

During the period from Sverre’s death in 1202, until Haakon

IY’s absolute sovereignty in 1240, artistic energies appear to have

flagged. But from 1240 to about 1320 is the flourishing period

of Gothic architecture in Norway as in England. The treatment

of form became lavish and lighter. The pointed arch, bell-shaped

capitals with round abacus, and beautifully and firmly modelled

foliage and deep mouldings

appeared. The windows are

either lancet-shaped or tra-

eeried. The east end, with

some few exceptions, is square.

Cross-vaulting is employed in

churches of more elaborate

design, the open roof in those

of simpler style.

From Trondhjem Cathedra).

In the east country, comparatively little was built in the

Gothic period, and only a few churches have been to some extent

preserved, for instance, Stange Church.

After 1272, the splendid choir in Stavanger Cathedral was

erected, and the bishop’s chapel; and in the neighbourhood, Utstein

Abbey.

Bergen was at this time Norway’s principal town, and here

a number of important buildings arose under the direct supervision

of Haakon IV and Magnus Lagaboter. All that is now le ft of