with water, answering to the erosion by the ends of the shorter

glaciers in the valleys.

A fairly regular series of shallower and less uniformly shaped

but often large lakes, is found in the Highland, even in most of

the large valleys just within the axis of' altitude, where, as a rule,

there are glens, isharn, leading to the corrresponding valley on the

west side. These glens are more or less deeply cut, trough-shaped

valleys that pass right across an imperceptible watershed. From

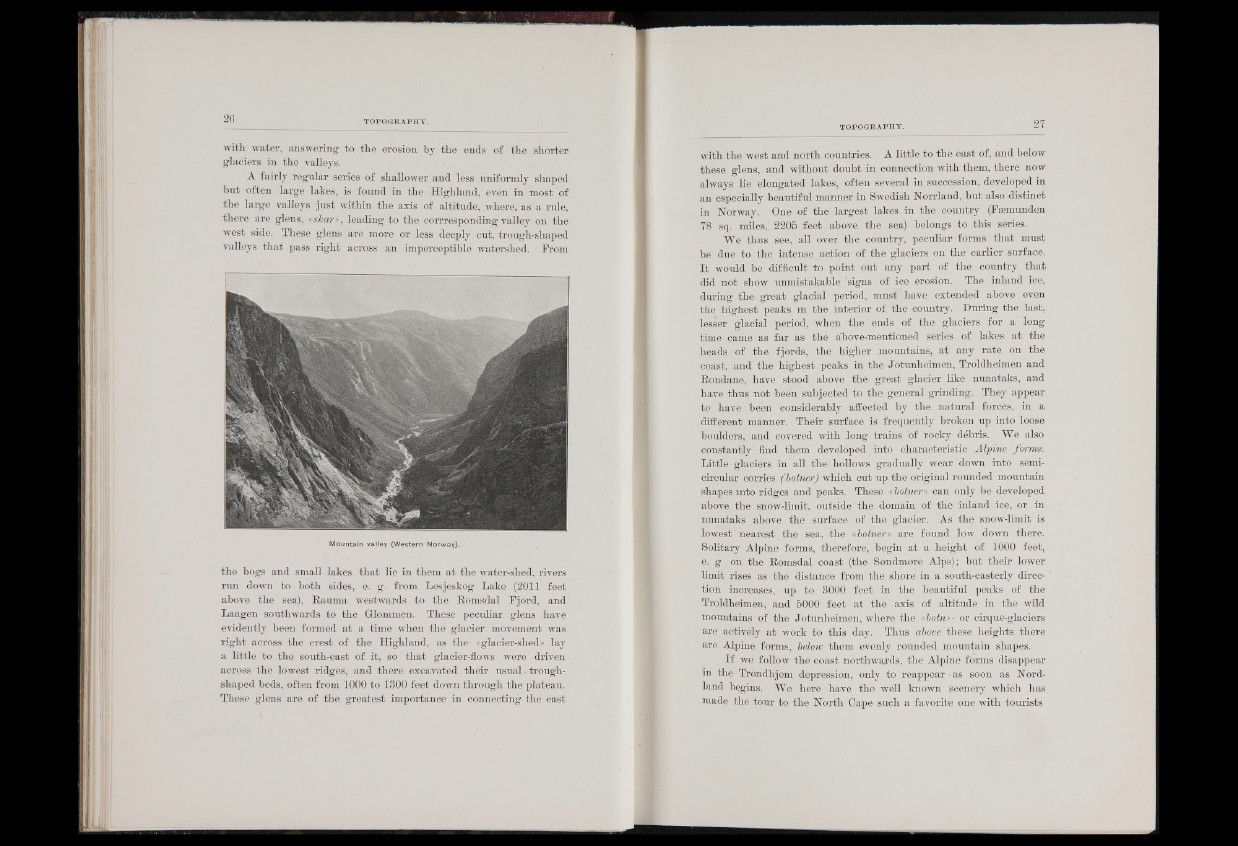

Mountain valley (Western Norway).

the bogs and small lakes that lie in them at the water-shed, rivers

run down to both sides, e, g. from Lesjeskog Lake (2011 feet

above the sea), Rauma westwards to the Romsdal Fjord, and

Laagen southwards to the Glommen. These peculiar glens have

evidently been formed at a time when the glacier movement was

right across the crest of the Highland, as the «glacier-shed» lay

a little to the south-east of it, so that glacier-flows were driven

across the lowest ridges, and there-excavated their usual. troughshaped

beds, often from 1000 to 1300 feet down through the plateau.

These glens are of the greatest importance in connecting the east

with the west and north-countries. A little to the east of, and below

these glens, and without doubt in connection with them, there now

always lie elongated lakes, often several in succession, developed in

an especially beautiful manner in Swedish Norrland, but also distinct

in Norway. One of the largest lakes in the country (Feemunden

78 sq. miles, 2205 feet above the sea) belongs to .this series.

We thus see, ,all over the country, peculiar forms that must

be due to the intense action of the glaciers on the earlier surface.

I t would be difficult to point out any part of the country that

did not show unmistakable 'signs of ice erosion. The inland ice,

during the. great glacial period, must have extended above even

the highest peaks in the interior of the country. During the last,

lesser glacial period, when the ends of the glaciers for a long

time came as far as the above-mentioned series of lakes at the

heads of the fjords, the higher mountains, at any rate on the

coast, and the highest peaks in the Jotunheimen, Troldheimen. and

Rondane, have stood above the great glacier like nunataks, and

have thus not been subjected to the general grinding. They appear

to have been considerably affected by the natural forces, in a

different manner. Their surface is frequently broken up into loose

boulders, and covered with long trains of rocky debris. We also

constantly find them developed into characteristic Alpine forms.

Little glaciers in all the hollows gradually wear down into semicircular

corries (botner) which cut up the original rounded mountain

shapes mto ridges and peaks. These «botner» can only be developed

above the snow-limit, outside the domain of the inland ice, or in

nunataks above the surface of the glacier. As the snow-limit is

lowest nearest the sea, the .«botner» are found low down there.

Solitary Alpine forms, therefore, begin at a height of 1000 feet,

e. g on the Romsdal coast (the Sondmore Alps); but their lower

limit rises as the distance from the shore in a south-easterly direction

increases, up to 3000 feet in the beautiful peaks of the

Troldheimen, and 5000 feet at the axis of altitude in the wild

mountains of the Jotunheimen, where the «botn»- or cirque-glaciers

are actively at work to this day. Thus above these heights there

are Alpine forms, below them evenly rounded mountain shapes.

If we follow the coast northwards, the Alpine forms disappear

m the Trondhjem depression, only to reappear-as soon as Nord-

land begins.' We here have the well known scenery which has

made the tour to the North Cape such a favorite one with tourists