Use of

hieroglyphics

in the East.

Sculpture of

the ancients.

and the bold style in which they, as well as the other written

characters which are found in this region, more particularly at

Persepolis and Bisutun, are executed, is well known. The

figures and writing engraven upon the cylinders found amongst

the ruins of Babylon, as well as the testimony of Herodotus,1

demonstrate that engraving upon metal and stone must have

been well understood previously to the destruction of that city.

The employment of hieroglyphics was anciently very general

in the East ;s and they are supposed, in many cases, to constitute

astronomical records.3

Public documents were inscribed or written on various materials,

besides bricks and stones, as on tablets of wood, copper,

or ivory, rolls of papyrus, the bark of trees,4 linen,5 and dyed

skins.6

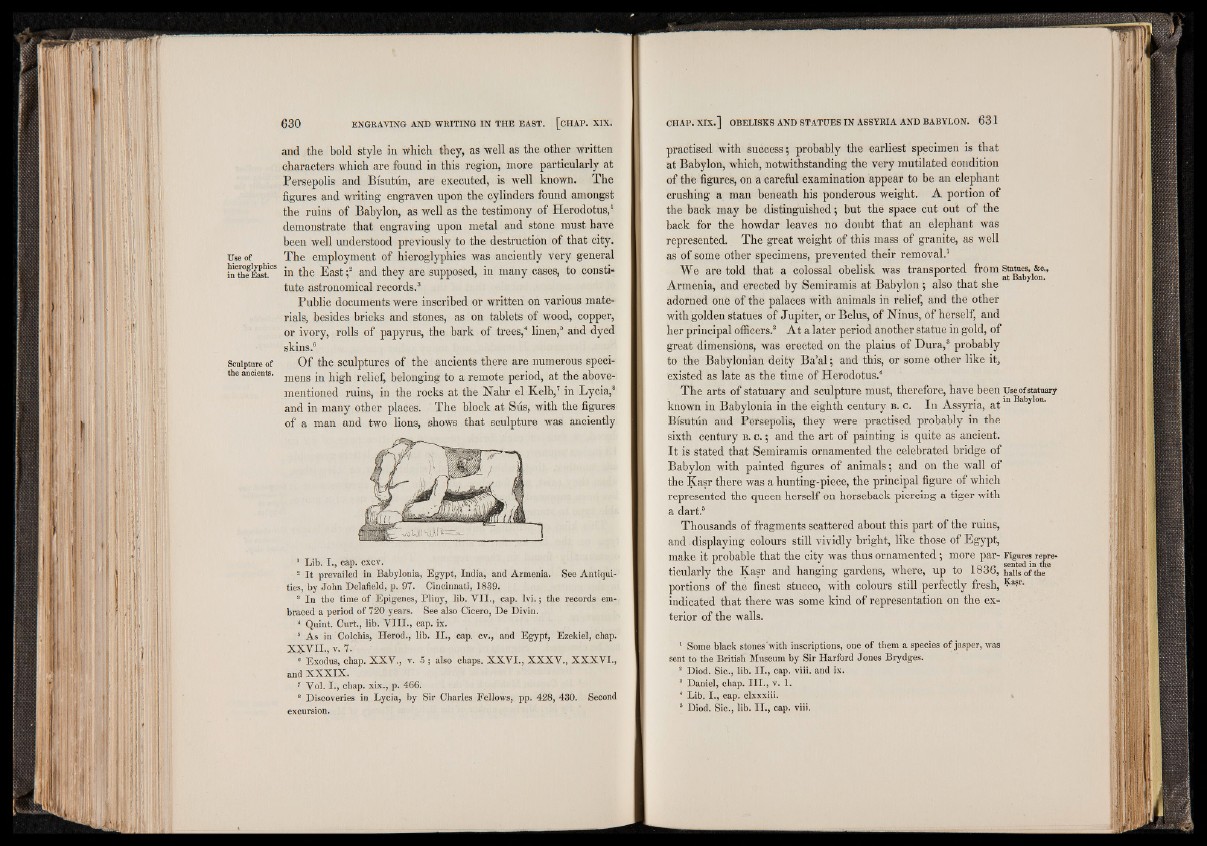

Of the sculptures of the ancients there are numerous specimens

in high relief, belonging to a remote period, at the above-

mentioned ruins, in the rocks at the Nahr el Kelb,7 in Lycia,8

and in many other places. The block at Siis, with the figures

of a man and two lions, shows that sculpture was anciently

1 Lib. I ., cap. cxcv.

2 I t prevailed in Babylonia, Egypt, India, and Armenia. See Antiquities,

by John Delafield, p. 97. Cincinnati, 1839.

8 In the time of Epigenes, Pliny, lib. V I I ., cap. Iv i.; the records embraced

a period of 720 years. See also Cicero, De Divin.

4 Quint. Curt., lib. V I I I ., cap. ix.

5 As in Colchis, Herod., lib. I I ., cap. cv., and Egypt, Ezekiel, chap.

X X V II., v. 7.

8 Exodus, chap. X X V ., v. 5 ; also chaps. X X V I., XX X V ., X X X V I.,

and X X X IX .

7 Vol. I ., chap. xix., p. 466.

8 Discoveries in Lycia, by Sir Charles Fellows, pp. 428, 430. Second

excursion.

practised with success ; probably the earliest specimen is that

at Babylon, which, notwithstanding the very mutilated Condition

of the figures, on a careful examination appear to be an elephant

crushing a man beneath his ponderous weight. A portion of

the back may be distinguished; but the space cut out of the

back for the howdar leaves no doubt that an elephant was

represented. The great weight of this mass of granite, as well

as of some other specimens, prevented their removal.1

We are told that a colossal obelisk was transported from statues, &c„

. . i i A . T _ a^ Babylon. Armenia, and erected by Semiramis at Babylon; also that she

adorned one of the palaces with animals in relief, and the other

with golden statues of Jupiter, or Belus, of Ninus, of herself, and

her principal officers.8 At a later period another statue in gold, of

great dimensions, was erected on the plains of Dura,3 probably

to the Babylonian deity Ba’al; and this, or some other like it,

existed as late as the time of Herodotus.4

The arts of statuary and sculpture must, therefore, have been Use ofstatuary

known in Babylonia in the eighth century b . c . In Assyria, a tm Babylon-

Bisutun and Persepolis, they were practised probably in the

sixth century b . c . ; and the art of painting is quite as ancient.

It is stated that Semiramis ornamented the celebrated bridge of

Babylon with painted figures of animals; and on the wall of

the Kasr there was a hunting-piece, the principal figure of which

represented the queen herself on horseback piercing a tiger with

a dart.5

Thousands of fragments scattered about this part of the ruins,

and displaying colours still vividly bright, like those of Egypt,

make it probable that the city was thus ornamented; more par- Figures repre-

ticularly the Kasr and hanging gardens, where, up to 1836, ham of the

portions of the finest stucco, with colours still perfectly fresh, ?a?r-

indicated that there was some kind of representation on the exterior

of the walls.

1 Some black stones'with inscriptions, one of them a species of jasper, was

sent to the British Museum hy Sir Harford Jones Brydges.

2 Diod. Sic., lib. I I ., cap. viii. and ix.

8 Daniel, chap. I I I ., v. 1.

* Lib. I ., cap. clxxxiii.

5 Diod. Sic., lib. I I ., cap. viii.