subject. An important result ensued, embodied in an interesting and

valuable report made by those gentlemen to the Commodore*

After a succession of daily conferences, which continued from the 8th to

the 17th of June, a mutual agreement was finally adjusted on the latter day,

in regard to the various disputed points of detail not specified in the treaty.

These are embodied in the following additional regulations:

* The following correspondence embraces the official action on this point:

Un it ed States F lag- s h ip P owhatan.

Simoda, June 12, 1854.

Gentlemen : Yon are hereby appointed to the duty of holding communication with

certain Japanese officials delegated by the imperial government, in conformity with the

treaty of Kanagawa, to arrange with officers, alike delegated by me, the rate of currency

and exchange which shall for the present govern the payments to be made, by the several

ships of the squadron, for articles that have been and are to be obtained; also to establish,

as far as can be done, the price at which coal, per picul or ton, can be delivered on board at

this port of Simoda.

I t is not to be understood that the rate of currency or exchange which may be agreed

upon at this time is to be permanent; on the contrary, it is intended only to answer immediate

purposes. Neither you nor myself are sufficiently acquainted with the purity and

value of the Japanese coins to establish a fixed rate of exchange, even if I had the power

to recognize such arrangement.

I t will, however, be very desirable for you to make yourselves acquainted with all the

peculiarities of the Japanese currency,-and also, if practicable, with the laws appertaining

thereto, as the information will be valuable in facilitating all future negotiations upon the

subject.

You will, of course, before entering into any agreement which may be considered

binding, refer to me.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

M. C. PERRY,

Commander in-Chief o f the United States Naval Forces in the

„ _ . _ „ Fast India and China Seas.

Purser Wil l ia m Sp e id en , United States Navy.

Purser J . C. E ldridge, United States Navy.

Un it ed States Steam-fr iga t e P owhatan,

Simoda, June 15, 1854.

Sir : The committee appointed by yon, in your letter of the 12th;instant, to confer with

a committee from the Japanese commissioners in reference to the rate of exchange and

currency between the two nations in the trade at the ports opened, and to settle the price

of coal to be delivered a t this port, beg leave to report:

The Japanese committee, it was soon seen, came to the conference with their minds

made up to adhere to the valuation they had already set upon our coins, even if the alternative

was the immediate cessation of trade. The basis upon which they made their calculation

was the nominal rate at which the government sells bullion when it is purchased

from the mint, and which seems also to be that by which the metal is received from the

mines. The Japanese have a decimal system of weight, like the Chinese, of catty, tael,

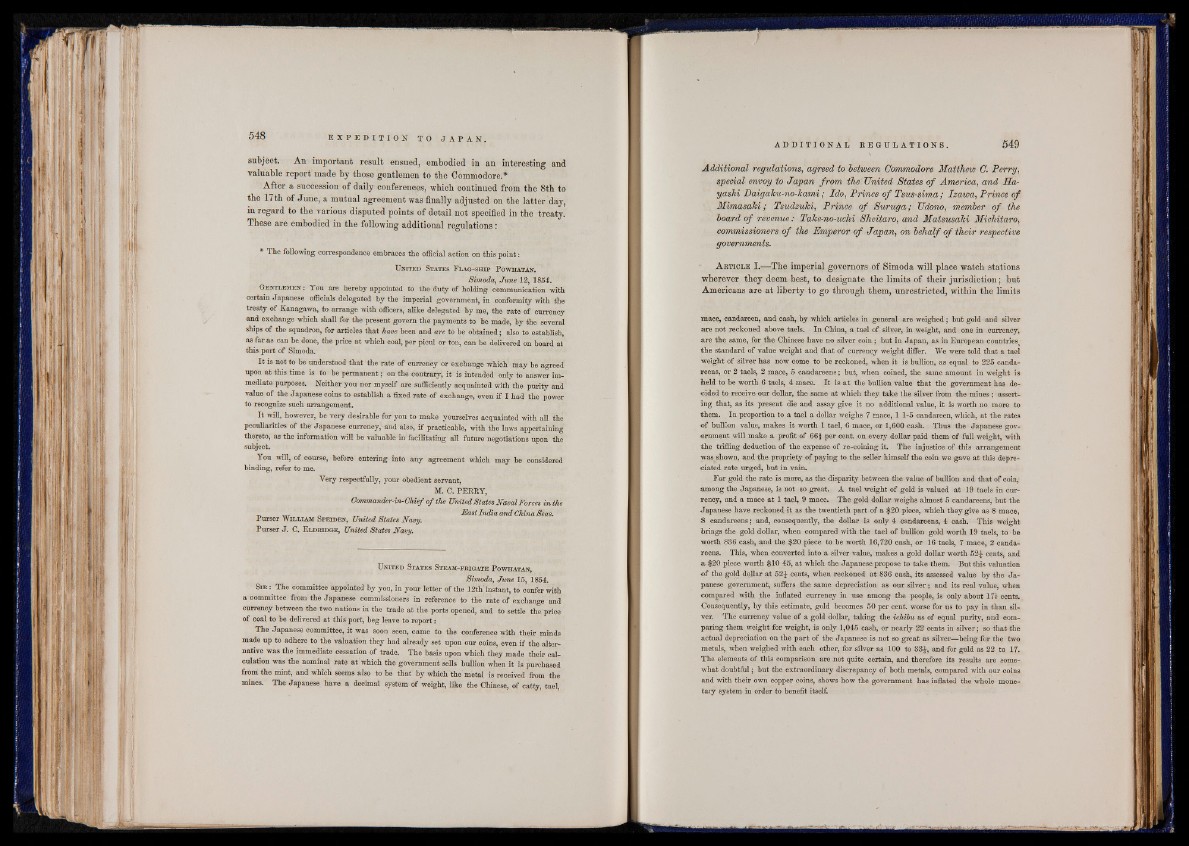

Additional regulations, agreed to between Commodore Matthew C. Perry,

special envoy to Japan from the United States o f America, and Ua-

yashi Daigaku-no-kami; Ido, Prince o f Tsus-sima ; Izawa, Prince of

Mimasaki; Tsudzuki, Prince o f Suruga; Udono, member o f the

board o f revenue: Take-no-uchi Sheitaro, and Matsusaki Michitaro,

commissioners o f the Emperor o f Japan, on behalf o f their respective

governments.

A rticle I.—The imperial governors of Simoda will place watch stations

wherever they deem best, to designate the limits of their jurisdiction; but

Americans are at liberty to go through them, unrestricted, within the limits

mace, candareen, and cash, by which articles in general are weighed; but gold and silver

are not reckoned above taels. In China, a tael of silver, in weight, and one in currency,

are the same, for the Chinese have no silver coin; but in Japan, as in European countries

the standard of value weight and that of currency weight differ. We were told that a tael

weight of silver has now come to be reckoned, when it is bullion, as equal to 225 canda-

reens, or 2 taels, 2 mace, 5 candareens; but, when coined, the same amount in weight is

held to be worth 6 taels, 4 mace. I t is a t the bullion value that the government has decided

to receive our dollar, the same at which they take the silver from the mines; asserting

that, as its present die and assay give it no additional value, it is worth no more to

them. In proportion to a tael a dollar weighs 7 mace, 1 1-5 candareen, which, at the rates

of bullion value, makes it worth 1 tael, 6 mace, or 1,600 cash. Thus the Japanese government

will make a profit of 661 per cent on eveiy dollar paid them of full weight, with

the trifling deduction of the expense of re-coining it. The injustice of this arrangement

was shown, and the propriety of paying to the seller himself the coin we gave at this depreciated

rate urged, but in vain.

For gold the rate is more, as the disparity between the value of bullion and that of coin,

among the Japanese, is not so great. A tael weight of gold is valued at 19 taels in currency,

and a mace at 1 tael, 9 mace. The gold dollar weighs almost 5 candareens, but the

Japanese have reckoned it as the twentieth part of a $20 piece, which they give as 8 mace,

8 candareens; and, consequently, the dollar is only 4 candareens, 4 cash. This weight

brings the gold dollar, when compared with the tael of bullion gold worth 19 taels, to be

worth 836 cash, and the $20 piece to be worth 16,720 cash, or 16 taels, 7 mace, 2 candareens.

This, when converted into a silver value, makes a gold dollar worth 52J cents, and

a $20 piece worth $10 45, at which the Japanese propose to take them. But this valuation

of the gold dollar at 52J cents, when reckoned at 836 cash, its assessed value by the J a panese

government, suffers the same depreciation as our silver; and its real value, when

compared with the inflated currency in use among the people, is only about 17± cents.

Consequently, by this estimate, gold becomes 50 per cent, worse for us to pay in than silver.

The currency value of a gold dollar, taking the ichibu as of equal purity, and comparing

them weight for weight, is only 1,045 cash, or nearly 22 cents in silver; so that the

actual depreciation on the part of the Japanese is not so great as silver—being for the two

metals, when weighed with each other, for silver as 100 to 33£, and for gold as 22 to 17.

The elements of this comparison are not quite certain, and therefore its results are somewhat

doubtful; but the extraordinary discrepancy of both metals, compared with our coins

and with their own copper coins, shows how the government has inflated the whole monetary

system in order to benefit itself.