kept pace with us, under their heavy loads, while our lazy and complaining

Chinamen lagged, behind. These coolies were mostly hoys, from twelve to

sixteen years of age. I noticed as a curious fact that, in spite of the heavy

loads they carried, and the rough hy-ways we frequently obliged them to

take, they never perspired in the least, nor partook of a drop of water, even

in the greatest heat. They were models of cheerfulness, alacrity, and

endurance, always in readiness, and never, by look or word, evincing the

least dissatisfaction. Our official conductors drank hut two or three times

of water during the whole journey. Tea appears to he the universal beverage

of refreshment. I t was always brought to us whenever we halted, and frequently

offered to Mr. Jones, as the head of the party, in passing through

villages. Once, at an humble fisherman’s village, when we asked for mizi,

which signifies cold water, they brought us a pot of hot water, which they

call yu, and were much surprised when we refused to drink it.

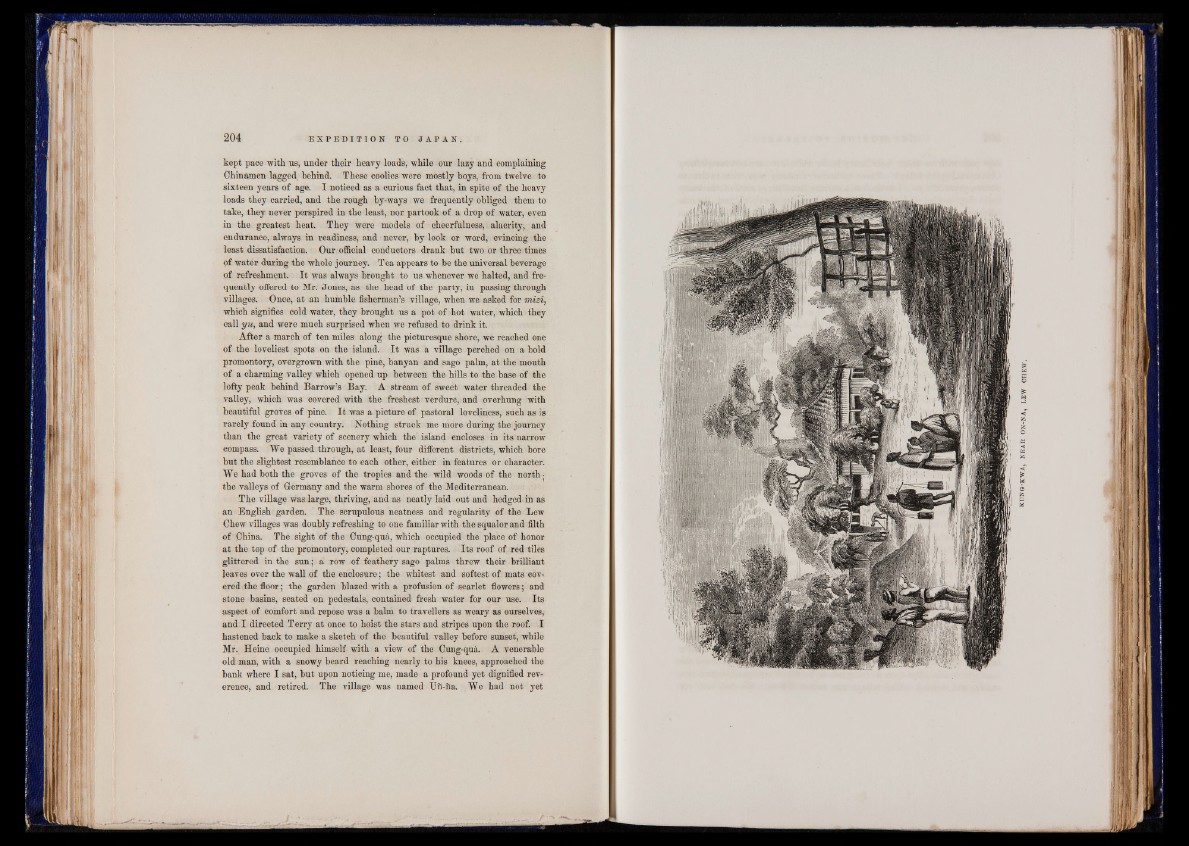

After a march of ten miles along the picturesque shore, we reached one

of the loveliest spots on the island. I t was a village perched on a hold

promontory, overgrown with the pine, banyan and sago palm, at the mouth

of a charming valley which opened up between the hills to the base of the

lofty peak behind Barrow’s Bay. A stream of sweet water threaded the

valley, which was covered with the freshest verdure, and overhung with

beautiful groves of pine. I t was a picture of pastoral loveliness, such as is

rarely found in any country. Nothing struck me more during the journey

than the great variety of scenery which the island encloses in its narrow

compass. We passed through, at least, four different districts, which bore

but the slightest resemblance to each other, either in features or character.

We had both the groves of the tropics and the wild woods of the north-

the valleys of Germany and the warm shores of the Mediterranean.

The village was large, thriving, and as neatly laid out and hedged in as

an English garden. The scrupulous neatness and regularity of the Lew

Chew villages was doubly refreshing to one familiar with the squalor and filth

of China. The sight of the Cung-qua, which occupied the place of honor

at the top of the promontory, completed our raptures. Its roof of red tiles

glittered in the sun; a row of feathery sago palms threw their brilliant

leaves over the wall of the enclosure; the whitest and softest of mats covered

the floor; the garden blazed with a profusion of scarlet flowers; and

stone basins, seated on pedestals, contained fresh water for our use. Its

aspect of comfort and repose was a balm to travellers as weary as ourselves,

and I directed Terry at once to hoist the stars and stripes upon the roof. I

hastened back to make a sketch of the beautiful valley before sunset, while

Mr. Heine occupied himself with a view of the Cung-qu4. A venerable

old man, with a snowy beard reaching nearly to his knees, approached the

bank where I sat, but upon noticing me, made a profound yet dignified reverence,

and retired. The village was named Un-fia. We had not yet