the least troubled by them. A little to the north of where we were the

island narrowed suddenly, between the head of the eastern bay and a deep

bight, which makes in on the western side, between Cape Broughton and the

headland bounding Port Melville on the west. I judged its breadth, at this

point, to be about four miles, in a straight line. To the southwest I could

see the position of Sheudi, eight or ten miles distant. The landscape was

rich and varied, all the hills being coated with groves of pine. We found

on the rock the “Wax plant” of our greenhouses, in full bloom, the splendid

scarlet Althcea, and a variety of the Malva, with a large yellow blossom.

Continuing our march along the summit ridge, we came gradually upon

a wilder and more broken region. Huge fragments of the same dark limestone

rock overhung our path, or lay tumbled along the slopes below us, as

if hurled there by some violent natural convulsion. As the hill curved eastward,

we saw on its southern side a series of immense square masses, separated

by deep fissures, reaching down the side nearly to its base. They were apparently

fifty feet high, and at least a hundred feet square, and their tops

were covered with a thick growth of trees and shrubbery. In the absence

of any traces of volcanic action, it is difficult to conceive how these detached

masses were distributed with such regularity, and carried to such a distance

from their original place. The eastern front of the crags under which we

passed was studded with tombs, some of them built against the rock and

whitewashed, like the tombs of the present inhabitants, but others excavated

within it, and evidently of great age. Looking down upon the bay it was

easy to see that the greater part of it was shallow, and in some places the

little fishing junks could not approach within half a mile of the shore. The

rice-fields were brought square down to the water’s edge, which was banked

up to prevent the tide from overflowing them, and I noticed many triangular

stone dykes, stretching some distance into the water, and no doubt intended

as weirs for fish.

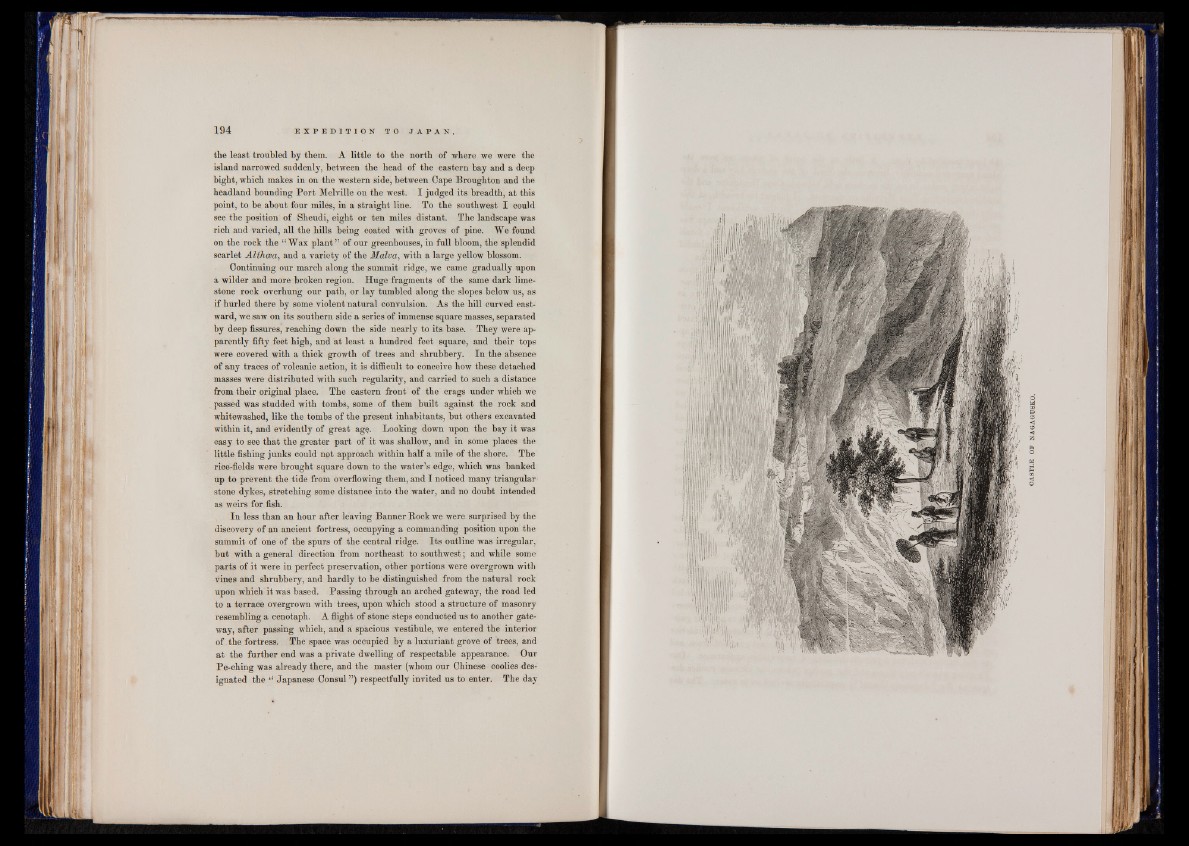

In less than an hour after leaving Banner Bock we were surprised by the

discovery of an ancient fortress, occupying a commanding position upon the

summit of one of the spurs of the central ridge. Its outline was irregular,

but with a general direction from northeast to southwest; and while some

parts of it were in perfect preservation, other portions were overgrown with

vines and shrubbery, and hardly to be distinguished from the natural rock

upon which it was based. Passing through an arched gateway, the road led

to a terrace overgrown with trees, upon which stood a structure of masonry

resembling a cenotaph. A flight of stone steps conducted us to another gateway,

after passing which, and a spacious vestibule, we entered the interior

of the fortress. The space was occupied by a luxuriant grove of trees, and

at the further end was a private dwelling of respectable appearance. Our

Pe-ching was already there, and the master (whom our Chinese coolies designated

the “ Japanese Consul ”) respectfully invited us to enter. The day