size of the hand. These shingles are fastened by means of pegs made of

bamboo, or kept in their places by long slips of board, which have large

rows of cobble stones put upon them to prevent their removal. The stones

are, however, said to have the additional advantage of hastening the melting

of the snow, which during the winter season is quite abundant at Hakodadi.

The gable ends, as in Dutch houses, face towards the street, and the roofs

projecting to some distance, serve as a cover and a shade to the doors. All

the roofs of the houses in front are topped with what at first was supposed

to be a curious chimney wrapped in straw, but which upon examination

turned out to be a tub, protected by its straw envelope from the effects of

the weather, and kept constantly filled with water, to be sprinkled upon the

shingled roofs, in case of fire, by means of a broom, which is always deposited

at hand, to be ready in an emergency. The people would seem to

be very anxious on the score of fires, from the precautions taken against

them. In addition to the tubs on the tops of the houses, there are wooden

cisterns arranged along the streets, and engines kept in constant readiness.

These latter have very much the general construction of our own, but are

deficient in that important part of the apparatus, an air chamber, and consequently

they throw the water, not with a continuous stream, but in short,

quick jets. Fire alarms, made of a thick piece of plank, hung on posts at

the corners of the streets, and protected by a small roofing, which are struck

by the watchman, in case of a fire breaking out, showed the anxious fears of

the inhabitants, and the charred timbers and ruins still remaining where a

hundred houses had stood but a few months before, proved the necessity of

the most careful precautions.

A few of the better houses and the temples are neatly roofed with

brown earthen tiles, laid in gutter form. The poorer people are forced to

content themselves with mere thatched hovels, the thatch of which is often

overgrown with a fertile crop of vegetables and grass, the seeds of which

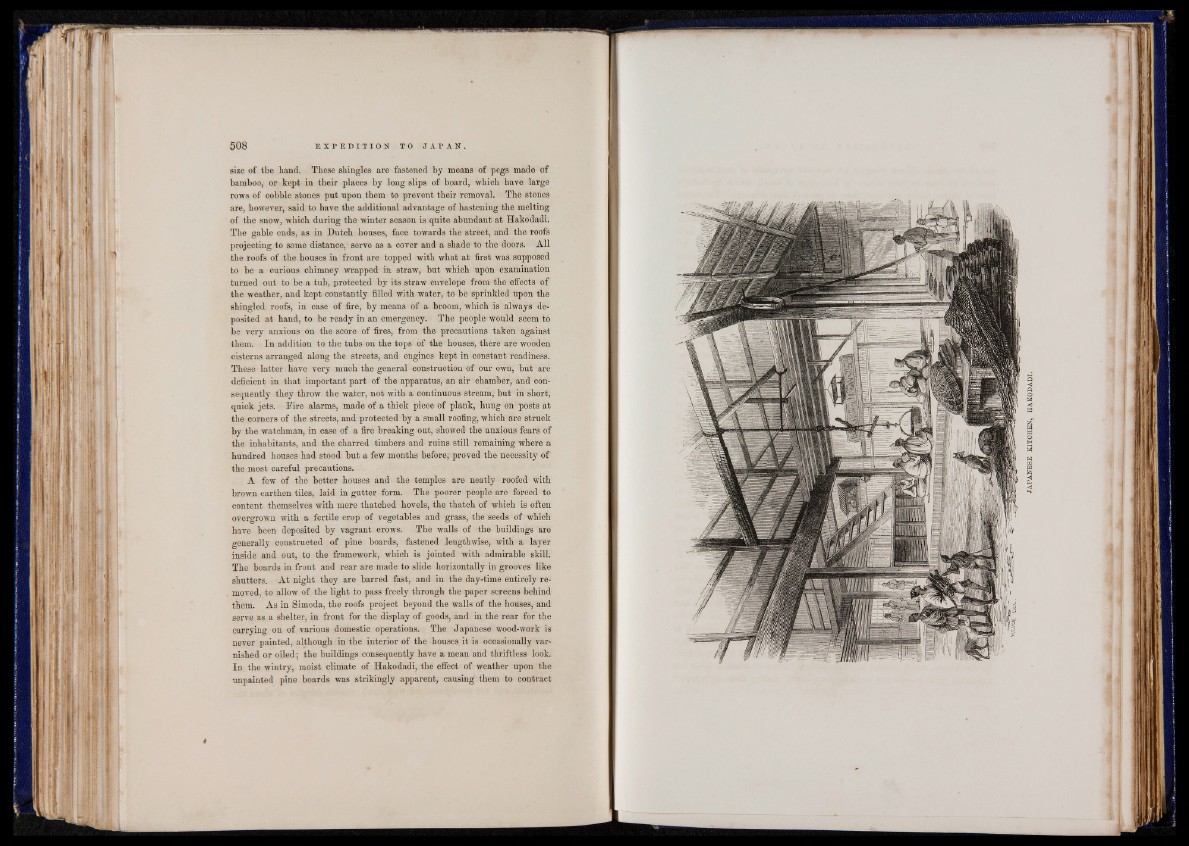

have been deposited by vagrant crows. The walls of the buildings are

generally constructed of pine boards, fastened lengthwise, with a layer

inside and out, to the framework, which is jointed with admirable skill.

The boards in front and rear are made to slide horizontally in grooves like

shutters. At night they are barred fast, and in the day-time entirely removed,

to allow of the light to pass freely through the paper screens behind

them. As in Simoda, the roofs project beyond the walls of the houses, and

serve as a shelter, in front for the display of goods, and in the rear for the

carrying on of various domestic operations. The Japanese wood-work is

never painted, although in the interior of the houses it is occasionally varnished

or oiled; the buildings consequently have a mean and thriftless look.

In the wintry, moist climate of Hakodadi, the effect of weather upon the

unpainted pine boards was strikingly apparent, causing them to contract

♦