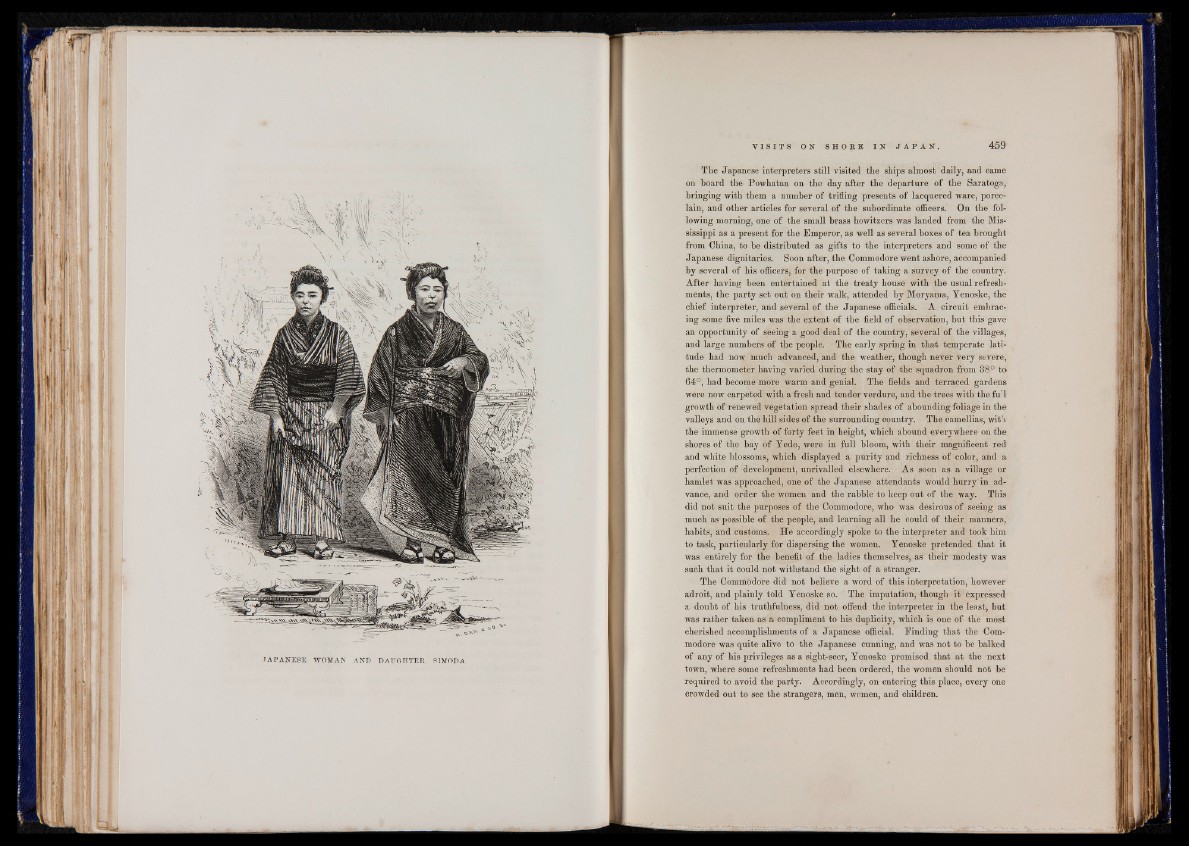

J A P A N E S E W O M A N A N D D A U G H T E R , S I M O D A

V I S I T S ON S H O R E I N J A P A N . 459

The Japanese interpreters still visited the ships almost daily, and came

on board the Powhatan on the day after the departure of the Saratoga,

bringing with them a number of trifling presents of lacquered ware, porcelain,

and other articles for several of the subordinate officers. On the following

morning, one of the small brass howitzers was landed from the Mississippi

as a present for the Emperor, as well as several boxes of tea brought

from China, to be distributed as gifts to the interpreters and some of the

Japanese dignitaries. Soon after, the Commodore went ashore, accompanied

by several of his officers, for the purpose of taking a survey of the country.

After having been entertained at the treaty house with the usual refreshments,

the party set out on their walk, attended by Moryama, Yenoske, the

chief interpreter, and several of the Japanese officials. A circuit embracing

some five miles was the extent of the field of observation, but this gave

an opportunity of seeing a good deal of the country, several of the villages,

and large numbers of the people. The early spring in that temperate latitude

had now much advanced, and the weather, though never very severe,

the thermometer having varied during the stay of the squadron from 38° to

64°, had become more warm and genial. The fields and terraced gardens

were now carpeted with a fresh and tender verdure, and the trees with the fuT

growth of renewed vegetation spread their shades of abounding foliage in the

valleys and on the hill sides of the surrounding country. The camellias, with

the immense growth of forty feet in height, which abound everywhere on the

shores of the bay of Yedo, were in full bloom, with their magnificent red

and white blossoms, which displayed a purity and richness of color, and a

perfection of development, unrivalled elsewhere. As soon as a village or

hamlet was approached, one of the Japanese attendants would hurry in advance,

and order the women and the rabble to keep out of the way. This

did not suit the purposes of the Commodore, who was desirous of seeing as

much as possible of the people, and learning all he could of their manners,

habits, and customs. He accordingly spoke to the interpreter and took him

to task, particularly for dispersing the women. Yenoske pretended that it

was entirely for the benefit of the ladies themselves, as their modesty was

such that it could not withstand the sight of a stranger.

The Commodore did not believe a word of this interpretation, however

adroit, and plainly told Yenoske so. The imputation, though it expressed

a doubt of his truthfulness, did not offend the interpreter in the least, but

was rather taken as a compliment to his duplicity, which is one of the most

cherished accomplishments of a Japanese official. Finding that the Commodore

was quite alive to the J apanese cunning, and was not to be balked

of any of his privileges as a sight-seer, Yenoske promised that at the next

town, where some refreshments had been ordered, the women should not be

required to avoid the party. Accordingly, on entering this place, every one

crowded out to see the strangers, men, women, and children.