finds himself quite at home, in the enjoyment of the most agreeable society;

for it is a custom of the merchants of the Bast to extend to strangers of respectability

a hospitality that is quite unreserved. Such, indeed, is the freedom

of the guest that he has only to order whatever he may require and his

demand is complied with at once. The master does not trouble himself about

the matter, but he is, for the most part of the time, away about his business;

and the whole concern of the household devolves upon the major-domo, whose

duty it is to satisfy every want. There is a very convenient official of these

establishments, termed a comprador, whose vooation it is to pay all the hills

accruing from the purchases and incidental expenses of the guests, who, however,

of course, refund what has been paid.

While enjoying the luxury of these oriental establishments, one, in fact,

might fancy himself in a well-organized French hotel, as he has only to express

a wish to have it gratified, were it not that he has nothing to pay in the

former beyond the usual gratuities to servants, while in the latter he is

mulcted roundly for every convenience.

There is not much at present to interest the visitor at Macao, as it is but

a ghost of its former self. There is almost a complete absence of trade or commerce.

The harbor is deserted, and the sumptuous dwellings and storehouses

of the old merchants are comparatively empty, while the Portuguese who inhabit

the place are but rarely seen, and seem listless and unoccupied. An

occasional Parsee, in high crowned cap and snowy robe, a venerable merchant,

and here and there a Jesuit priest, with his flock of youthful disciples, may be

seen, but they are only as the decaying monuments of the past.

At one time, however, the town of Macao was one of the most flourishing

marts of the Bast. When the Portuguese obtained possession, in the latter

part of the sixteenth century, they soon established it as the centre of a wide

commerce with China and other oriental countries. Its origin is attributed

to a few Portuguese merchants belonging to Lampacayo, who were allowed

to resort there and establish some temporary huts for shelter and the drying

of damaged goods. Hue, the Chinese traveller, gives a different account; he

states that the Portuguese were allowed to settle by the Emperor, in return

for the signal service of capturing a famous pirate who had long ravaged the

coasts. From an humble beginning, the settlement gradually arose to an imposing

position as a commercial place, for which it was greatly indebted to

the monopoly it enjoyed of eastern commerce. I t has, however, declined,

and is now a place of very inconsiderable importance and trade.

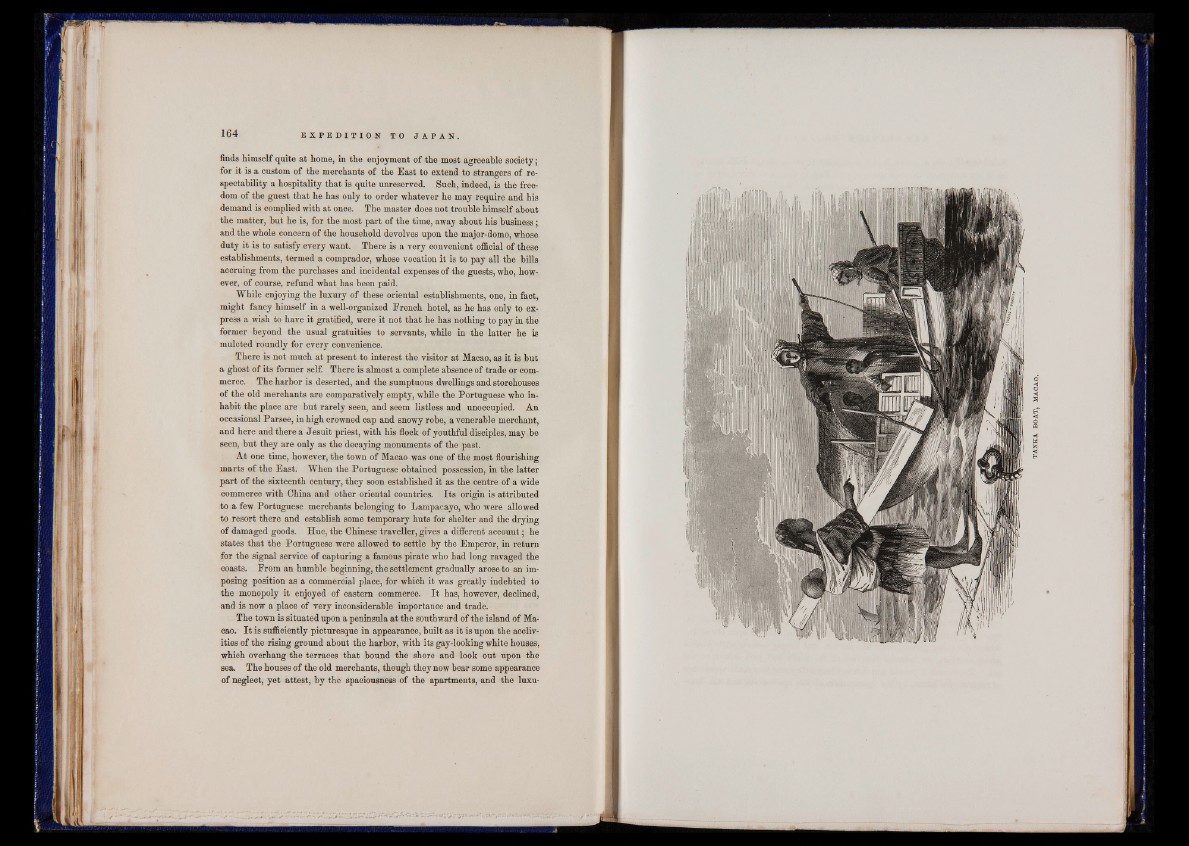

The town is situated upon a peninsula at the southward of the island of Macao.

I t is sufficiently picturesque in appearance, built as it is upon the acclivities

of the rising ground about the harbor, with its gay-looking white houses,

which overhang the terraces that bound the shore and look out upon the

sea. The houses of the old merchants, though they now bear some appearance

of neglect, yet attest, by the spaciousness of the apartments, and the luxu